Vaccines are a topic that stir up a lot of emotions. How should we talk about them? Will anything we do make a difference? I think a useful perspective on the topic comes from framing the question somewhat differently: can we make a difference by the way behave in our interactions with other people?

When I first encountered vaccine skepticism at a mommy-group, I found myself on a furious Google and PubMed-fest, pasting from scientific sources and official health authorities. The thread went south. The worst names we called each other may only have been ‘irresponsible’, ‘ignorant’, and ‘biased’, but going on 150 comments, each time that notification button turned red it added double digits to my blood pressure. I’d wake up at 3 am to feed the baby, unable to get back to sleep thinking of *how they could just not get it*. Giving up on sleep, I’d answer adjuvant questions at 3:45.

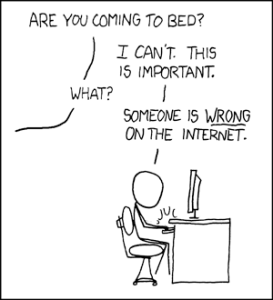

It was your classic case of ‘somebody is wrong on the internet’ (xkcd). And here’s the thing. Despite the time, effort, and sacrificed peace of mind (mine and others), I don’t think I changed any minds.

During that time there was this one mom, who puzzled me. She was arguing in support of vaccines, too, but instead of tersely correcting the misinformation like I did (^2), she would be very polite, appeal to the emotional side of the subject, and ask follow-up questions on what it was exactly that made some of the other moms concerned. She was The Nice Mom.

I didn’t get that. I could not respect comments about vaccinating being ‘a very personal decision’. This was about science. How could Mrs Nice Mom be so chummy to people who were endangering kids’ lives? I for one galloped ahead on my high horse. I felt it was a moral duty not to let one little piece of misinformation get away unaddressed, lest it continue to infect the minds of others.

I did a few round of these debates. I was miserable. I just wanted to make the world better, but it resulted in people disliking me. I debated leaving the mommy groups. I wanted to sleep at night. I knew my dad had high blood pressure, should I be worried?

Eventually I think people on the forums just began avoiding the V-word, for fear of yet another uncomfortable comment-marathon. Meanwhile I silently compiled a 46-page resource document on vaccines and vaccine myths for my mental peace.

One day it occurred to me that I had been hearing the same kind of laments (“how can they not get it”) with friends back in the University, only the topic had been the environment – both, by the way, are complex topics where direct short term harm or benefits are not obvious or visible, a point elaborated by the New Scientist:

“The first thing to note is that denial finds its most fertile ground in areas where the science must be taken on trust. There is no denial of antibiotics, which visibly work. But there is denial of vaccines, which we are merely told will prevent diseases – diseases, moreover, which most of us have never seen, ironically because the vaccines work.”

So, me and fellow Ecology students often talked about why people made harmful choices on matters of the environment, and a friend of mine argued that the majority of people were simply too stupid, egocentric, and lazy to do any better.

I remember feeling my neck hair rise at that. I launched into a passionate defence of humanity in response, something along these lines:

The world is complex. The issues are complex and information is confusing. But most of us don’t even get that far. Why?

Because it is not particularly easy to exist. For many, just getting up in the morning, dealing with their own state of mind, their families and loved ones or the lack of them, their aches and pains, their performance at work or school, their bad bosses and bullying work-mates, their half-empty bank-accounts and what have you, can well and truly be too much. There are endless difficulties in just being a person and dealing with the hand you’ve been dealt. Maybe there are people who don’t have too much trouble living, who knows. But for me, even though I’ve been fortunate in many ways, life has never been a breeze. Existential anguish and all that:

In existentialism, the individual’s starting point is characterized by what has been called “the existential attitude”, or a sense of disorientation and confusion in the face of an apparently meaningless or absurd world.

Existence is hard. Not being on board with sophisticated scientific breakthroughs on top of that makes you… egocentric and stupid? That explanation just doesn’t cut it.

As it turns out, there is a lot of research supporting just this sort of difficulty to come to terms with the absurdity of life as the main source of the problem. Feelings of powerlessness and cynicism are at the core of people losing their faith in health authorities, governments, and science, and even believing that they are deeply corrupted to the point of conspiracy, leading to movements such as the anti-vaxxers.

It is not so easy, on top of living, to also deal with things such as economic recessions, threats (and actual occurrences) of terrorist attacks, autoimmune disease epidemics, and looming natural disasters. As written on the topic by the New York Times:

Conspiracy theories also seem to be more compelling to those with low self-worth, especially with regard to their sense of agency in the world at large. Conspiracy theories appear to be a way of reacting to uncertainty and powerlessness.

“If you know the truth and others don’t, that’s one way you can reassert feelings of having agency,” Swami says. It can be comforting to do your own research even if that research is flawed.

Finding your own truth and sticking to it may be a necessary piece holding it all together. At the face of stressful uncertainties, we could even hypothesise that there are significant therapeutic benefits in ‘reasserting feelings of your agency’. Saying no is a vastly more empowering action than simply accepting the complicated and carefully formulated statements from authorities and experts far away, particularly when that no is emotionally supported by your friends and family.

There is more bad news. Not only can there be psychologically valid reasons for denying the science on vaccines, changing people’s minds with rational arguments can be nigh impossible. There’s confirmation bias or ‘motivated reasoning’ to deal with, which may actually cause the efforts of informing to backfire – cementing the audience’s views.

Put bluntly – by being rude to a person who does not support vaccination, you may not be achieving anything other than treating another human badly.

I may not know anything about the personal circumstances of the person I am talking to. It would probably be better to for me to try not to take their statements or stances personally. Did I *really have to* call people out on their irrationalities at every turn? (Boy is this difficult. Sitting on my hands helps.) Maybe there was something else I could do, as drowning somebody with legitimate sources and multitude of rational objections didn’t do much for anyone’s sanity or happiness.

In this context I think it is even more tragic when I read reports from people who are not against vaccines, but who simply want to find out, and are buried in insults for even asking questions, like Kathy McGrath who wrote about her vaccine research as a guest at the parenting blog Red Wine and Apple Sauce:

“I was stunned by the passionate and rapid-fire judgmental comments from both camps and initially retreated from conversation as I became further alienated by both sides.”

Right at that time when I was struggling with how to talk about vaccines, I could not have been happier to have stumbled on this simple piece of advice.

It seems that every time an anti-vaxxer has the courage to comment on a scientific thread, blog, video, etc. the internet is quick to fire. There is name calling, shaming, and even threats of death. […]

We’re scientists after all, and scientists trust the data. The data say that in order to effectively teach these people we should be probing their understanding. Ask them why they believe vaccines cause autism. Ask them to explain the biochemical mechanisms that cause the toxicity of preservatives. Ask them to describe how a well controlled clinical trial is conducted. When they flounder point them in the right direction.

They described the method better know as The Socratic Method. Really, I was hitting my head against the wall when a better answer had been found in the ancient Greece? It gave me pause to realise that this was pretty much what Mrs Nice Mom had been doing. The one who had always managed to express her support for vaccines while still remaining liked and respected by everyone.

I decided to put it to test. I used friendly curiosity, probing for the underlying understanding of my audience. I asked them how they determined who or what to listen to as a source of information, and if they could teach me how I could know what they have come to know. How did it work? Where should I turn to to find out? What should I do if two sources contradicted each other?

The next couple of discussions were strikingly different (this one was on vaccines and eczema):

“dear Ilda [sic], I wouldn’t know of those myself. toxins hang around the body, don’t they and the skin condition is a red flag for the imbalance they cause inside…”

There was no debate. Maybe they were simply not interested to continue. Maybe we just avoided an argument. I could hope they would think more about the topics on their own, but I honestly don’t know.

But the effect on me was tremendous. I was calm. I was polite, curious, friendly and happy. I became sincerely interested in how they had gotten to the conclusions they’d made. I reflected upon how difficult it could be to actually find something out, and felt a cooperative sense of puzzlement in wondering with them how you could know more about ‘toxins’, what they would be, and what their effects on the body would be.

Not shooting someone down with counter-arguments was awesome. I had helped keep the atmosphere friendly while the incredible claims had dwindled and dried up, hopefully demonstrating to other readers what a feeble ground they stood on.

So was that as good as it gets? Just avoiding the argument, with no guarantee that the vaccine (or general science) skeptics would actually reassess their views? Some argue just that:

“This unfortunately means that it is highly unlikely, if not impossible, to change the mind of an anti-vaccine believer, since in order to do that, you’d have to completely change how they assign weight to evidence, akin to trying to convince a religious person to become an atheist on the basis of rational arguments.

And that is something you and I may not be able to do in the vast majority of cases.”

I am trying to learn the age-old wisdom to accept the things you cannot change. There will always be people who can not be convinced. But certainly it is true that we *do* influence each other, and that reason *does* often carry a special weight in convincing us. It’s a mix of emotions, reason, and trust. There are good reminders that, of course, we shouldn’t abandon rational arguments altogether.

But how we lead the debate makes a big difference. How we treat others affects both us and them, as well as the spread of the information. Here philosopher Daniel Dennett’s useful summary of how to criticise with kindness:

-

You should attempt to re-express your target’s position so clearly, vividly, and fairly that your target says, “Thanks, I wish I’d thought of putting it that way.

-

You should list any points of agreement (especially if they are not matters of general or widespread agreement).

-

You should mention anything you have learned from your target.

-

Only then are you permitted to say so much as a word of rebuttal or criticism.

In order to lead a civil and respectful debate, understanding the opposing point of view really does make a difference. I found an interview of the poet and essayist Eula Biss doing her own research on vaccines unusually helpful on this regard. It helped me reflect on the place vaccines have in our psychology and the society we live in. I don’t want to view the world as a place where there is a somehow hostile opposing crowd called ‘the anti-vaxxers’ or ‘the anti-science people’. I want to understand how the world works, and that includes both the bodies *and* the minds of the people in it. Eula Biss reminds us that things are hardly ever simple:

That’s one of the more interesting and surprising things I discovered: people had really varied reasons for not vaccinating. I think if we had to group all those reasons together — which I just said we can’t and shouldn’t do! — I think there is a kind of fear of the unknown under it all. Vaccination is kind of emblematic of something that feels to people like something they don’t fully understand, or they’re afraid science doesn’t fully understand. The fear is that we don’t really know what we’re doing to our body when we do this, and it might have consequences we can’t foresee.

She also elaborates on the philosophy of the vaccine debate:

It’s a social debate that’s being conducted in the terms of science. We’re using the language of science and the products of the scientific process to talk about other things. [such as…] what is the relationship between the individual and the collective? What does the individual owe society, and what does society owe the individual?

That touches on something important. Vaccines are a social debate – that’s also the key for something that science has uncovered about what it is that makes a difference in the debate. What is it, most of all, that influences people’s decision on vaccines? It’s not evidence – not at first hand and not for most of us. It’s friends and family.

From: The Impact of Social Networks on Parents’ Vaccination Decisions

This is important to note because of all of the variables considered in this study, the percent of network members recommending nonconformity was the most important in terms of predicting parents’ vaccination decisions. Considered by itself, this variable was more predictive of parents’ vaccination decisions than any demographic or general characteristic of parents or their networks. It was also more predictive than the percent of parents’ source networks recommending nonconformity and even parents’ own perceptions of vaccination.

There is a crucial role for people who pay attention to and understand the role of scientific evidence. How that influence is asserted may have less to do with the debates we take head on with people who disagree with us, and more with the atmosphere of science communication that we inspire in our own friends and loved ones. And if we do have someone in our own circle who rejects vaccines, who do you think will help change their mind – the friend who is tolerant of their views, wishes to understand them, and serves as a like-minded example of a contrary view, or the one who shoots out of their life in a big blast of conflict?

I honestly don’t know if I could be that understanding friend. But I know I would like to be.

In her interview Eula Biss offered thoughtful words of understanding of the anger people like me feel when faced with people determined not to vaccinate. But she also offered the most poetic description of herd immunity that I’ve read:

Here’s a system that’s based on people voluntarily using their bodies to protect other vulnerable people. I just think that’s very different than a lot of what we see in this competitive, mercenary space of capitalism.

The root question is a question of how do we live together? What’s a responsible way to be a citizen? And I think those are big questions that are then, complicated, by the historical and political baggage that people bring to the conversation.

There is a sentiment here that applies to all of us – whether we are talking about vaccination, or how we want to treat any other members of the society whose views are otherwise different from our own.

What is the best way to live together?

Our aluminium deodorant discussion will always stay with me, and changed the way that I will think now, one hundred percent. I question things, I stop just believing in something because I have always known it to be right… Some kind of knowledge osmosis. Well, it’s more so that I just question it now. I don’t have the desire to spend hours trawling through the internet for evidence one way or another, but I definitely don’t go sprouting Truths any more, as I now know that what I deem as obvious and logical may not actually be so, and may in fact be completely wrong. The reason that this stuck with me and changed my thinking? Not because of the discussion we had at the time, where you questioned me and plied me with statistics and sources, but because of what I actually SAW in the real you, not the internet you, afterwards. I saw how this had affected you, how my irrationality had upset you and made you question yourself and your own choices, and the anguish that had caused you. It was only then that it actually made me think. The internet will never be able to do that.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: Myth: no studies compare the health of unvaccinated and vaccinated people | Thoughtscapism

Hi, I am new here. I just had to say that reading your posts…well, they are a breath of fresh air. I am usually The Nice Mom on debate posts. Thanks to reading your other post, I finally feel I have some understanding regarding the underlying forces driving the divisive of the election. Then I saw THIS post. And, now I know why the election (the fighting, the ugliness, the insults, the broad-brushed generalities) have been so frustrating and triggering for me. I am the mother of three, two of whom are autistic. My husband is autistic. My mother and brother are autistic. I identify as spectrum. Two of my grandparents would have surely been diagnosed autistic, one from each side of the family. I have countless relatives that are either autistic or have the typical co-morbid syndromes and disorders. The vaccine business is a regular hot topic in my life. (I personally vaccinated all my children.) I do have two friends who are heavily into the anti-vax movement. (We simply have to agree to disagree.) I really, REALLY like the way you spell out the underlying issues that drive these debates. I am fascinated with understanding and identifying what drives human bahvior. So, your thoughtful presentation is quite refreshing and informative and comforting for me. I finally feel like I am not alone in my drive to understand the “why” in a world gone mad!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hello Lisa,

I am so happy to read this. Thank you very much for letting me know. You are not alone.

I am very glad to hear that you are able to stay friends despite your differences. I hope more of us may learn to live that way!

Iida/Thoughtscapism

LikeLike

Hey, I’ve just discovered your website and the more I read the more I like. I know this is confirmation type bias but you are crystallizing much of my more muddled thinking on these topics. I look forward to a lot more reading of your contributions.

LikeLike