I have written about my journey going from an enthusiastic organic supporter to a reluctant avoider of organic products in my piece Natural Assumptions, and afterward I received harsh criticism from one organic farmer. I have learned my lesson about remaining open to evidence, so I wanted to take the opportunity to review his points carefully to make sure I had not been too hasty in my conclusions about organic farming. (This piece was originally published in February 2015 and updated in April 2016.) In a three-part series of posts, I will offer my response to the criticism posted on the comments section of the Skepti Forum Blog by Rob Wallbrigde (who blogs over at The Fanning Mill). I thank him for his interest in civil debate, and for providing me with a detailed 6-point list of issues he saw with my piece, making this discussion possible. I will go into more detail on the aspects of 1) nutritional content, 2) animal welfare, 3) pesticides, 4) environmental impact, 5) yield differences, and 6) the origins of organic farming. The answers got lengthy. The two last points are dealt with in a post of their own, Delving deeper into the roots of organic.

I have written about my journey going from an enthusiastic organic supporter to a reluctant avoider of organic products in my piece Natural Assumptions, and afterward I received harsh criticism from one organic farmer. I have learned my lesson about remaining open to evidence, so I wanted to take the opportunity to review his points carefully to make sure I had not been too hasty in my conclusions about organic farming. (This piece was originally published in February 2015 and updated in April 2016.) In a three-part series of posts, I will offer my response to the criticism posted on the comments section of the Skepti Forum Blog by Rob Wallbrigde (who blogs over at The Fanning Mill). I thank him for his interest in civil debate, and for providing me with a detailed 6-point list of issues he saw with my piece, making this discussion possible. I will go into more detail on the aspects of 1) nutritional content, 2) animal welfare, 3) pesticides, 4) environmental impact, 5) yield differences, and 6) the origins of organic farming. The answers got lengthy. The two last points are dealt with in a post of their own, Delving deeper into the roots of organic.

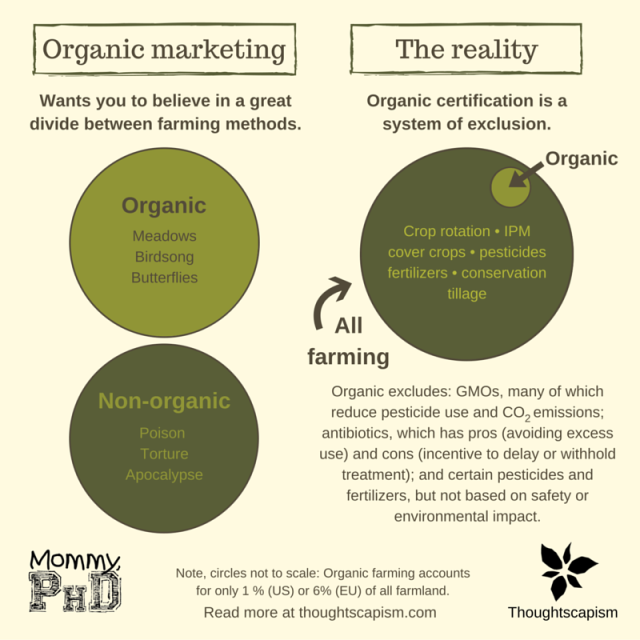

Unfortunately many mistaken ideas about organic farming stem from the misleading tactics of organic marketers. Infographic created together with neuroscientist Alison Bernstein aka Mommy PhD, who came up with the idea behind it. Statistics on European organic farming can be found here, and you can read more about pesticides, antibiotics, GMOs, conservation tillage, and crop rotations in the piece below.

1) Nutritional value of organic vs conventional

This point I have already talked about as a case study in the context of bias, here: Am I biased? Are you?, and on its own, here: Organic vs conventional food. Shortly, the criticism was as follows:

1) The Stanford study is not the only meta-analysis conducted on organic food, it has been criticized for excluded data and poor statistical analysis, and other studies have reached opposite conclusions. (e.g. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/249681031 ) I think it’s more accurate to say that the jury is still out on this one.

No cherry picking

Summary answer repeating the gist of my pieces above, is that several comprehensive reviews support the view I have presented, namely no nutritional or health benefits for organic products. You may also read Novella’s analysis of the study Rob cited above. It is the only review to reach the opposite conclusion, and the significance of that conclusion is questionable. The study is outlined also in the Conversation by Ian Musgrave: Organic food is still not more nutritious than conventional food.

2) Animal welfare – it’s not that simple

Criticism from Rob Wallbridge:

2) Animal welfare is one of the core principles of organic agriculture, and organic standards make specific and detailed references to livestock production, including animal welfare. So while it may be true that organic is “no guarantee” of superior animal welfare across the board, it is certainly inaccurate to portray it as “more narrowly focused on the farming of crops.” (A German newspaper article hardly qualifies as a definitive source.)

I think it’s important for my children to have a close relationship with animals

What comes to animal welfare in organic farming, I have found some indications of problems, and little proof of benefits. If you, the reader, know of studies on this topic one way or another, I am sincerely interested and hope that you will send them my way. I have been a vegetarian or semi-vegetarian for a large part of my life and that is mostly because I feel deeply for sentient beings and am concerned about animal welfare.

While I am heartened about hearing of special care being taken of livestock, I can no longer just take someone’s word on that being true. I need to have some kind of proof. I want to read what regulations there are, if and how they are controlled, and if they live up to the standards. I have heard several optimistic accounts from farmers about animal husbandry in general – conventional farmers as well as organic, and I do hope that people treat their farm animals well, after all, they are their livelihood.

What I learned after reading that mentioned respected Swiss animal welfare organisation warning that bio label does not necessarily mean much difference for the animals (news article in german) concerning Swiss animal husbandry, was that this animal welfare organisation in question was also the independent controlling body for animal welfare in Switzerland. My research (all in german, though italian and french probably available as well) on the fine print of the labels confirms that the ‘bio’ (organic) labels did not have specific regulations in place for animal treatment, only on their feed (specifically no GMOs, only organically grown). That leaves animal welfare for ‘bio’ in neither a better or worse status than the conventionally bred livestock.

Organic certification: no antibiotics

What concerns me, however, are reports of treatment of organic livestock in case of illness. A former organic farmer wrote a piece over at Random rationality blog, called Why I’m Through with Organic Farming. In it he argues that organic farmers have an incentive to forgo efficient treatment of sick animals, while instead treating them with natural cures and homeopathy (water pills):

Both MOFGA and the NOP make it clear that livestock must not be subject to the “routine use of synthetic medications.” Antibiotics cannot be used “for any reason.” And yet:

“Producers are prohibited from withholding treatment from a sick or injured animal; however, animals treated with a prohibited medication may not be sold as organic.”

So an animal treated with appropriate medications is thereby rendered unclean.

OK, whatever. There are other ways of treating your animals that pass “organic” muster, according to “Raising Organic Livestock in Maine: MOFGA Accepted Health Practices, Products and Ingredients.” In case of mastitis, for instance, you could have the cow take “garlic internally, 1 or 2 whole bulbs twice a day” or put “dilute garlic in vulva” (using Nitrile gloves made in Thailand, one hopes). Then there are the “Homeopathic remedies, Bryonia, Phytolacca,” and other letters of the alphabet.

It is worth noting that excess use of antibiotics is not recommended and may provide opportunities for development of antibiotic resistance, and organic certification’s ban on antibiotics makes sure farmers avoid this drawback. Luckily most of the antibiotics used on animals are not used in humans, and their contribution to multi-resistant bacterial diseases among human seems small (over-prescription of antibiotics to humans is deemed the biggest culprit here – Debunking Denialism talks of these issues here). Still, proper treatment of sick animals is something I would definitely demand from a label that should guarantee best animal treatment, and here the organic brand fails me.

Studies of animal welfare

One study I have read about looks at US dairy cows, and it shows few differences and several similar shortcomings what comes to the standards of treatment of both organic and conventional dairy cows. Science-minded dairy farmers who very sincerely seem to care for their animals have not shown great concern when I have asked them about this study. I have heard speculation that the kind of standards that were so frequently failed in this study would have more to do with being up to date with paperwork and having written procedures in place for handling a number of possible problems – probably good things to have, but it doesn’t necessarily imply poor animal treatment in practice. Whatever the case, neither does it show that buying organic would get me products from animals treated any better.

Regular Swiss summer traffic

Another scientific paper very relevant to this topic is one titled “Animal Health and Welfare Issues Facing Organic Production Systems” (you can download the paper in pdf format by clicking here). This paper highlights the advantage that the organic label has what comes to animal welfare – consumers are interested in an animal friendly standard, and organic could serve this purpose. General animal welfare regulations can vary greatly from country to country, whereas organic could have a global standard for a level of animal welfare guaranteed through regular farm audits.

The primary welfare risk identified in the literature in organic management systems appears to be related to biological function, specifically animal health. The other main domains of animal welfare including affective state and the ability to perform natural behaviors in organics systems have not been well studied. These domains however appear to be the ones that resonate most with consumers when they consider welfare in organic systems due to assumptions of increased outdoor access, space and ability to perform natural behaviors. This is a potential area for the organic livestock farming industry that needs to be quantified as it could be a documented benefit which would compensate for other deficiencies.

The paper acknowledges the risks of alternative medicine and its potential result of prolonged animal suffering (for background, the prohibitive terms of the use of conventional medicine for USDA Organic can be found here §205.238 Livestock health care practice standard).

Other labels that focus on animal welfare

Bottom line, are organic animals happier? That is a very difficult thing to quantify. I have understood that the US organic rules are not very specific what comes to the living conditions of the animals, for instance, whereas Canadian ones are much more prescriptive. There are some factors even in the US rules, however, that should be contributing positively. I would like to see that animals have access to pastures or the outdoors, and the organic standards of the USDA NOP (§205.239 Livestock living conditions) do guarantee that ruminant animals graze at least 120 days per year, getting minimum 30 % of their feed during that time from the pasture. Rest of the year, as well as a month around calving, and another four months days at the end of their life (‘finishing’) they can also be kept at feedlots (which fills the criteria for ‘access to the outdoors’). Feedlots are given a bad rep, but not being an expert, I can’t confirm one way or another. I have heard consultants who work with several farms comment that it is highly dependant on how each individual operation is kept.

My cow namesake, Iida, born at a friend’s farm. I slept with the calf in the straw a few hours after her birth. Helping bring the cows in for milking shortly afterward, the calf’s mother Ektar took one sniff at me and thought I was her lost calf. I never forget her dark cow eyes and soft moos as she kept following me along the fence.

I would like to add that I am the target market for an “animal friendly” label. I would like to pay more to be sure to buy products from animals that are given a low-stress environment, ample space and access to the outdoors, the possibility to express their natural behaviours, and interact with each other. I think that organic could become that label, and I hope they do. For that to happen, I do argue that the important aspects of animal wellbeing should be more carefully formulated. I don’t want to pay more for the use of homeopathics or the exclusion of GMO feed – I want extra happy and healthy animals, preferably with carefully defined standards developed by animal behaviour experts.

In fact, there are other existing labels more focused on just this topic. In Switzerland, I have discovered the label Naturafarm – it is one primarily concerned with animal welfare, audited by the Swiss Animal Protection (Sweizcher Tierschutz STS), and distinct from organic product lines.

Meanwhile, as I have learned more about conventional animal handling, I have understood that it is not in the best interest of either the farmers or the industry to have animals that suffer – it would hurt their results as well. As naive as it is to think that no farmer would ever treat their animals badly, it is just as naive to imagine that most farmers would be involved in a routined culture of maltreatment. Suffering animals are as bad for the heart as they are for the farm.

3) The nature of pesticides

Here is the criticism I received from Rob Wallbridge:

3) The pesticide study you cite was a theoretical exercise based on the assumption that organic farmers would use pesticides in the same manner as conventional farmers. They conducted no research to determine how organic farmers actually manage soybean pests, and what type of pesticides they would use (if any), and at what rates. Actual field research demonstrates significant environmental impact advantages to integrated and organic approaches: http://www.agr.gc.ca/eng/?id=12991771856291

The link provided by Rob above is not a scientific paper, and does not go counter any conclusions I made in my piece Natural Assumptions. The argument I do make is about which pesticides are allowed in organic farming (synthetic vs ‘natural’) and why. I am sure there are good and bad ways of using all pesticides, and both conventional and organic farmers should be knowledgeable in the best ways of applying pest control. Reading the criticism above, I can’t help but note that if one wishes to argue that organic farming is better because of *how* they apply pesticides, not *which* pesticides are allowed, I do think the rules of organic should be changed to reflect the usage, rather than the arbitrary exclusion of some chemicals in favour of others, and this without evidence of lesser harm.

Agricultural scientists Steve Savage talks about this in his piece Why You Can Feel Guilt-free Buying Non-Organic Produce:

Some organic approved pesticides are very benign (low hazard) materials, but so are a great many of the synthetic pesticides used by conventional farmers. Some organic-approved pesticides are slightly to moderately toxic. This is also the case for synthetics. There are many pesticides that are used by both conventional and organic growers. Some of the pesticides commonly used on organic crops are applied at rather high rates (pounds per treated acre). Some are approved for use until almost immediately before harvest. In any case, organic-approved pesticides definitely leave residues on treated crops by the time they reach the consumer.

The unfortunate marketing of organic as the healthier or more environmental choice because of being free of synthetic pesticides is a misleading marketing tactic. Sometimes it even goes way beyond that, and crosses over to hate speech and propaganda against conventional farming. In order for the organic label to regain my respect, it should transparently recognise that other factors are much more important. Factors such as how the pesticides are applied, how practising no-till, crop-rotation, using cover crops and energy-efficient farming methods are where the focus should be for the environment’s sake.

The unfortunate marketing of organic as the healthier or more environmental choice because of being free of synthetic pesticides is a misleading marketing tactic. Sometimes it even goes way beyond that, and crosses over to hate speech and propaganda against conventional farming. In order for the organic label to regain my respect, it should transparently recognise that other factors are much more important. Factors such as how the pesticides are applied, how practising no-till, crop-rotation, using cover crops and energy-efficient farming methods are where the focus should be for the environment’s sake.

Fear of fruits and vegetables as a sales tactic

Organic marketing wishes to imply that eating conventional produce is not healthy. But eating more of fruits and vegetables, whether organic or conventional, is hands down one of the most important factors for a healthier diet. Making people afraid of eating vegetables with no basis in evidence is not an ethical practice. You can read A half a dozen reasons to ignore the Dirty Dozen to learn about the Environmental Working Group’s baseless attempts to frighten consumers into buying organic.

This image of healthfulness is false on so many levels. While conventional synthetic pesticide residues are regularly tested for and found to be of no concern to consumers, organic pesticides have so far remained outside of any testing regimen (read more by Steve Savage at: Pesticide Residues on Organic: What Do We Know?). Some wine farmers are even switching from organic citing health and environmental issues of organic allowed pesticides vs those available for non-organic farmers. Meanwhile, organic marketing perpetuates the idea of organic as ‘pesticide free’, happily forgetting to mention the kinds of pesticides that are used in organic farming.

In my piece I referenced three pesticide-connected papers which highlighted the point that the nature of a pesticide is not inherently different for being synthetic or natural, and that the ‘pesticide free’ image is playing on fear, because pesticides cause nearly no risk at all to the consumer.

The Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences (IFAS) brings some valuable perspective to the question of pesticides: how harmful are they? They write:

Although there have been pesticides that were toxic and dangerous to handle, most of these products are no longer used and have been replaced by newer chemistry. Pesticides now must go through rigorous testing by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) before they can be sold. This has led to many herbicides that possess little or no mammalian toxicity and are less harmful than many everyday household products (Table 1). Surprisingly, household chemicals that many of us store under the kitchen sink pose more risk to the handler than herbicides.

I also mentioned a great practice that is widely applied in organic faming: Integrated Pest Management (IPM). This was in the context of choosing best methods for the environment. Fortunately this is also a big part of conventional farming. In my piece Myth: UN calls for small-scale organic farming, I mention that according to the USDA, IPM has been incorporated at over 70 % of US farms since the year 2000.

Another good method that can help avoid pest-problems is crop-rotation. In another one of my pieces, Monocultures – the great evil of modern Ag?, I discuss the use of crop rotations at length. Suffice it to say that organic farmers are by no means alone in applying crop-rotations on their fields: USDA reports that currently the majority of crops in the US are farmed using crop rotations (82-96 % of cropland for most crops).

I argue that the organic dictated dichotomy of pesticides (synthetic vs natural) is artificial, and instead I support the use of scientific evidence for determining the best possible methods of pest control, not restricting oneself to those which are allowed within the organic certification, based on assumption rather than evidence. I hope we are in agreement there.

4) Environmental impacts of farming

The next point of criticism was as follows:

4) As for nutrient management, it’s a big stretch to look at the results of a single greenhouse study in Israel and extrapolate them to criticize organic farming in general. As for the meta-review, reading the actual research rather than a newspaper columnist’s opinion of it, leads to very different conclusions. To quote (with my comments in square brackets): “The only impacts that were found to differ significantly between the systems were soil organic matter content [higher/better in organic], nitrogen leaching, nitrous oxide emissions per unit of field area [both lower/better in organic], energy use [lower/better in organic] and land use [higher/worse in organic]. Most of the studies that compared biodiversity in organic and conventional farming demonstrated lower environmental impacts from organic farming.” The author ends with a call for an approach that does beyond the simple conventional vs. organic dichotomy.

I agree that a single study of anything shouldn’t be used for a conclusive look at things in general. I am not doing that. I’m afraid the comment above misrepresents the meta-analysis “Does organic farming reduce environmental impacts?” however. The paper points out problems with nitrogen leaching and nitrous oxide in organic agriculture. The bracket additions in Rob’s comment make statements that go counter the results in the paper. (During a discussion on Food and Farm Discussion Lab, Rob charitably acknowledged as much.)

I agree that a single study of anything shouldn’t be used for a conclusive look at things in general. I am not doing that. I’m afraid the comment above misrepresents the meta-analysis “Does organic farming reduce environmental impacts?” however. The paper points out problems with nitrogen leaching and nitrous oxide in organic agriculture. The bracket additions in Rob’s comment make statements that go counter the results in the paper. (During a discussion on Food and Farm Discussion Lab, Rob charitably acknowledged as much.)

I would also like to quote from the conclusion in the abstract, which highlights once more the problem regarding yield in organic systems. The data quoted in the criticism were in the category where they are favourable to organic, that is, the results per field area. Unfortunately those benefits turn to drawbacks when compared per product unit (because organic yields are lower, we need more field area to produce the same amount of crop). Another quote from the meta-analysis Does organic farming reduce environmental impacts? (my emphasis):

The results show that organic farming practices generally have positive impacts on the environment per unit of area, but not necessarily per product unit. Organic farms tend to have higher soil organic matter content and lower nutrient losses (nitrogen leaching, nitrous oxide emissions and ammonia emissions) per unit of field area. However, ammonia emissions, nitrogen leaching and nitrous oxide emissions per product unit were higher from organic systems. Organic systems had lower energy requirements, but higher land use, eutrophication potential and acidification potential per product unit.

Specifically, looking at page 17, graph “B – Non-LCA impacts per unit of product”:

- Nitrogen leeching is significantly higher in organic systems (the star * denotes the differences that are determined statistically significant – which means it is very unlikely that differences were due to chance).

- Nitrous oxide and an ammonia emission in the same graph show slightly higher or similar impact as conventional – practically similar levels. Organic farming is not more beneficial.

- Graph on page 18: land use for organic was also significantly higher.

To highlight what this means, you can read more about how nitrogen leaching is indeed a big problem for the environment.

Environmental impacts – greenhouse gasses

Another surprising little detail, which isn’t so little in the context of greenhouse gases, is the carbon footprint of compost. Composted manure is the fertilisation method of choice in organic farming. Should that method be adopted on large scale, its methane emissions would become a considerable problem. Agricultural technology professional Steve Savage takes a well referenced look at composting issues, and provides a calculation of average emissions per acre:

a mid-range [compost] use of 5 tons/acre would represent a carbon footprint of 10,833 pounds (CO2 equivalents). This is without including the fuel footprint of hauling the compost to the field and spreading it.

To put this in context, he also provides a comparison of the above carbon footprint of the compost needed for that one acre to many other examples, for instance:

-

The complete carbon footprint of producing 5.7 acres of conventional corn (including fertilizer, crop protection chemicals, seed, fuel, nitrous oxide emissions from soil…)

-

The carbon footprint of growing, handling and transporting 9,641 pounds of bananas from Costa Rica to Germany

He also highlights a much better carbon-offsetting method of dealing with animal waste, that is adopted by water refinement facilities and large Cattle Feeding Operations. Taken together with the increased nitrogen leaching, I think it is safe to conclude that the understandable wish to use animal manure as fertiliser is environmentally not as clear cut as it may seem. Also, if we were to move to all organic farming, we would much more cattle to produce all the necessary manure. Organic farming is already dependent on manure from conventional cattle for their manure needs. From Environmental Research Web:

On average, organic farms in the study received 73% of their phosphorus from conventional farming, 53% of their potassium and 23% of their nitrogen.

Finally, I would like to underscore that the conclusions which the meta-analysis‘ abstract ends with is exactly what my piece also advocates for. The best methods, whether they be derived from organic or conventional practices, should be used for the goal of most efficient and environmentally friendly farming.

The key challenges in conventional farming are to improve soil quality (by versatile crop rotations and additions of organic material), recycle nutrients and enhance and protect biodiversity. In organic farming, the main challenges are to improve the nutrient management and increase yields. In order to reduce the environmental impacts of farming in Europe, research efforts and policies should be targeted to developing farming systems that produce high yields with low negative environmental impacts drawing on techniques from both organic and conventional systems.

Right now, I believe the only real dichotomy is the one created by organic farming. It excludes several methods from consideration on the basis of an artificial categorisation (no synthetics, no GMOs). Conventional farming has no such drawback, and it can, and should, use science for its direction of development.

Environmental benefits of conventional farming

In fact, I have read several papers highlighting the benefits of modern (organic-forbidden) farming methods for environment. Here is an article that argues farm efficiency to be a good measure for impact on climate change. To clarify what efficiency means in practice, I’ll borrow Marc Brazeau’s words over at Genetic Literacy Project:

High yields are an indicator of efficient use of resources. High yields indicate that water, fuel, fertilizer, pesticides, labor, etc were successfully transformed into food instead weeds, bug food, and run off.

You can read more in my piece: GMOs and the environment

Another important tool, forbidden in organic farming but bringing big environmental benefits, are GMO crops. Here are studies on the key environmental impacts that crop biotechnology has had on global agriculture in 2012 and 2013:

The adoption of GM insect resistant and herbicide tolerant technology has reduced pesticide spraying by 553 million kg (-8.6%) and, as a result, decreased the environmental impact associated with herbicide and insecticide use on these crops (as measured by the indicator the Environmental Impact Quotient (EIQ)) by19.1%. The technology has also facilitated important cuts in fuel use and tillage changes, resulting in a significant reduction in the release of greenhouse gas emissions from the GM cropping area. In 2013, this was equivalent to removing 12.4 million cars from the roads.

And here is an article by the US Department of Agriculture on the environmentally beneficial no-till method that is spreading thanks to adoption of Herbicide Tolerant (HT) genetically engineered varieties.

These trends suggest that HT crop adoption facilitates the use of conservation tillage practices. In addition, a review of several econometric studies points to a two-way causal relationship between the adoption of HT crops and conservation tillage. Thus, in addition to its direct effects on herbicide usage, adoption of herbicide-tolerant crops indirectly benefits the environment by encouraging the use of conservation tillage.

The way I see it, being labeled organic really shouldn’t stand in the way of choosing environmentally friendlier methods. Looking at the evidence I can find, sadly at this time this seems to be the case. It’s conventional farming that has the freedom to choose among many methods which are favourable for the environment. I’ll end with a quote from farmer Richard Wilkins in an article from Washington post, “Organic standards fight over synthetics shows there’s room for a third system”:

He rotates his crops (corn, wheat, soy and vegetables), plants cover crops and pays a lot of attention to the health of his soil. When I asked him if he ever considered growing organically, he said, “I’m too much of a believer in the benefits of science and technology to go organic.”

For more pieces on these topics, you can find my collections of articles under Farming and GMOs or The Environment.

If you would like to ask a question or have a discussion in the comments below, you are very welcome, but please take note of my Commenting policy. In a nutshell:

- Be respectful.

- Back up your claims with evidence.

Pingback: Delving deeper into the roots of organic | Thoughtscapism

Pingback: GMOs and the environment | Thoughtscapism

Pingback: [Trad] Les OGM et l’environnement | La Théière Cosmique

Pingback: Am I biased? Are you? | Thoughtscapism

Pingback: Organic vs conventional food | Thoughtscapism

Pingback: Plants don’t have problems | Thoughtscapism

Pingback: Organic Vs. Non-Organic Food: Which Is More Nutritious?

Hi!

Great article! Finally someone who takes the ecological perspective in this debate. It is constantly rotating around human health issues in the fat west and it makes me tired.

There is an alternative to “organic” meat in Germany: Neuland http://www.neuland-fleisch.de/landwirte/neuland-erzeuger-haben-vorteile.html

I still have not managed to find details of their regulations, but I find the concept interesting. Neuland consists of farmers who grew tired of the organic label process, which is both expensive and long and decided to start up their own label that focused more on animal welfare. They still are non-GMO, but I presume that they had to if they were to sell any meat at all in the Berlin area…

It should be noted that “organic” vs “conventional” can mean a huge difference for products from certain areas such as seafood. Also, in the developing world it can mean that usage of highly toxic compounds are not permitted protecting the farmers. I underline CAN mean. I think the issue is more complex that be for or against “organic” and that the main problem lies in the labeling jungle (I am currently writing an article on just that and it makes me quite upset!).

Thank you again for a great article!

/ Anna from The Imaginarium

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Iida

Like you, I care very deeply about the environmental friendliness and sustainability of our food and have been consuming Swiss bio products (almost exclusively) for many years, in the idea that this helps. Also like you, I am very attached to science and the scientific method (have been doing scientific research for the past ~7 years or so, albeit not in the life sciences).

Needless to say given the above, that your writings on the subject of bio agriculture have absolutely intrigued me. However, on careful consideration, I think they are missing a bigger picture (beyond single details like using GMOs or synthetic substances). Here is an attempt to explain what I mean, though I am certainly not as good at writing as you are.

The evidence you’re presenting above shows that some types of “organic” agriculture (the ones studied in all those references) have some issues. Yet you seem to be drawing the conclusion that bio agriculture in general (does that even exist??? there are so many standards/labels!) is netly(?) inferior to conventional agriculture in general (again, I doubt one can throw all conventional agriculture practices in one big pot and make statement about the whole pot). Some types of conventional agriculture have issues too (different from the one listed above) and I think we’re a long way from finding the perfect agricultural system.

I entirely agree that whatever that system is called/labelled (bio/organic/conventional etc) it should be open to new scientific findings, new ideas and generally evolvable — with the note that findings/ideas need to be thoroughly confirmed both “in lab”/theoretically, as well as in practice on a larger scale, before being officially adopted as part of a standard.

I don’t know about other standards, but I believe the Swiss Bio Knospe standard definitely aims to fulfil these requirements, as far as I can tell. Here is the 2015 edition of their requirements (available in 5 languages) http://www.bio-suisse.ch/en/downloads.php

Just from skimming, as I don’t currently have time for more, I would like to point to a few points relevant to your current post (and related ones):

— evolvability: “Bio Suisse continually updates its standards. A production operation may contribute ideas and help shape these standards through its member organization or by participating in Bio Suisse committees.”

— environment: “‘Bud’ market partners agree to improve the environmental footprint of their

operation or business over the long term. They refrain from seeking a market advantage at the expense of the environment.”

— energy efficiency: page 94

— social accountability: the entirety of section 4 in part I.

— fair pricing: in section 5 of part I

— limitation on the distance travelled by fertilizers that come from outside of a bio-operation (aka farm) – page 84 at the bottom.

So, yes, MAYBE excluding _all_ GMOs and synthetic fertilizers/pesticides is less than ideal and a lot to do with image as well. But I will have that any day over mostly profit-driven, industrialized/factory farming with no sense of social responsibility, fair pricing and so on.

In other words: bio/organic agriculture is constrained in the use of GMOs and some synthetic substances; but conventional agriculture is far from being as free as you portray it: the main driver was, is and will be profit — anything else is a side effect. And profit-hunting is almost never compatible with protecting the environment, in fact, it is mostly exactly opposite: http://www.exposingtruth.com/new-un-report-finds-almost-no-industry-profitable-if-environmental-costs-were-included/

Many rules of bio agriculture are beneficial and there is no need for science to prove that (e.g.social responsibility, fair pricing etc). Some rules may be questionable, but I cannot agree that they are inherently bad.

GMOs (in the current state of how they’re marketed and sold, not in their original scientific vision), are still very controversial and cannot be analyzed as a whole (see the successful case of papaya vs. the more controversial cases of soy and corn).

On synthetic fertilizers/pesticides, I admit I am less informed, but assuming they are 100% beneficial, it is a price I personally would be ready to pay for the rest of the “bio package”. Also, as a side note, a Greenpeace analysis has shown that the amounts of pesticides/herbicides in conventional produce in Germany/Austria is often much higher than the amounts permitted by legislation. If this much makes it to the produce, how much still ends up in the environment and what are the consequences? (e.g. on bees, (super)weeds and other entities).

On the origins of bio agriculture: yes, there was the “mystic” current that turned into present-day Demeter. But there is also the not-unrelated, but largely parallel current that turned into the Bio Knospe, and which is more science-rooted. (See here, hoping you read German: https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/%C3%96kologische_Landwirtschaft).

On the higher use of land of bio agriculture: this one does trouble me a lot. However, again, it is a matter of _overall_ cost versus benefit. Could it be that this extra cost is offset by the sum of beneifts? I am unaware of any comprehensive/”panoramic” study comparing family-farm based bio agriculture, to industrial/factory-based conventional agriculture…

So, my current preference for produce is: 1. family-farm over industrial (industrial may be more efficient in some ways, but it has lots of large scale, severe issues and no incentives to solve them). 2. bio over conventional (not because I believe that bio is inherently better — I believe it’s very difficult to properly assess which one is overall better — but because bio has many “guaranteed” principles to which I adhere, while conventional could go either way, depending on incentives).

Finally, regardless of the debate, here is some reading you find interesting:

— the KAG Freiland standard (www.kagfreiland.ch) is the highest animal welfare standard in Switzerland and probably one of the highest in the world.

— Eating Animals by Jonathan Safran Foer – a very objective treatment of animal factory-farming with lots of researched details. As a small example, it very well illustrates the fate of the animal manure resulting from these farms and the huge problems it’s causing. Using this manure to grow plants seems much better than spraying it over populated areas, just saying…

— The World according to Monsanto by Marie Monique Robin (the book, not the movie) – a very detailed and well documented, award-winning history of Monsanto and its practices. After reading this, any hope I had that something good may ever come out of Monsanto has vanished. P.S. I had never heard about Monsanto before reading this book, so I went in completely prejudice-free.

All in all, while the scientific method and its results are of utmost importance, not everything reduces to that. Not everything can be found in scientific studies, there is also a reality out there, which may contradict them, factors that could never be accounted for in a study and may radically change its results etc…

Just out of curiosity, which bio-standard(s) are the cited studies referring to?

Ok, I have to go to bed now 🙂 Hope I will not have bored you too much with my writing…

Good night!

A

LikeLike

Hi Andreea! Thanks for your thoughtful comments, I appreciate you taking the time to look up all those sources, especially the Swiss specifics. I look forward to checking all your links and making a proper reply in a few days – birthday party for my 2 year old and visitor this weekend 🙂

Have a great weekend!

Iida

LikeLike

No problem, take your time! And happy birthday! 🙂

We’re also having a 2 yo party next weekend!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hello again Andreea! Thanks we had a great birthday 🙂 Happy birthday to your little one too in advance!

I’m really happy that you show such interest in this topic. I used to think farming was an important topic just because of my passion for the environment, but now I’ve learned a lot of fascination in the science of farming itself. I hope you find some of the further sources here helpful. I’m sorry it got so long… there’s so much to say, and I wanted to give you good answers to what is behind my conclusions.

So, firstly … I used to believe that organic labels in different countries could have very different definitions, and was surprised to find that the rules were in fact pretty similar. It is explained in part by their common roots – biodynamic agriculture – and roof organisations – International Federation of Organic Agriculture Movements IFOAM, http://www.ifoam.bio/

From the Bio Suisse:

“Swiss farmers played an instrumental role in the evolution of organic farming. Soon after Dr. Rudolf Steiner founded biodynamic agriculture in 1924, farming operations were started in Switzerland which utilized his methods and adapted them to local climatic and structural conditions. In the 1940s, Dr. Hans Müller developed the ‘organic-biological’ method. ”

The common roots being in biodynamic farming is a warning sign, and gets us onto very sketchy ground scientifically speaking. Buried animal organs stuffed with herbs and the like, and I’m not kidding! (see table of biodynamic preparations in https://thoughtscapism.com/2015/02/24/delving-deeper-into-the-roots-of-organic/).

Still, bio farming could have evolved to an evidence-based way to try to use the most environmentally friendly farming methods. But unfortunately what is the most important point and common denominator for all bio, all around the world, is this (again from Bio Suisse):

“We use natural means.”

The idea that ‘natural’ methods are best in a mysterious way that was above and beyond evidence – no bio movement or certification ever justifies this. They are not even looking to justify it with any evidence. They use natural, because it’s natural, even where evidence shows that ‘synthetic’ methods are better for the environment. They don’t need to consider that, because that is not natural, – and ultimately, that’s not their marketing tactic. All farming is profit driven. There is no difference there between bio and non-bio. If farming operation is not profitable, it is not going to continue. Also, if it’s not profitable, it is wasting it’s resources, as they are being poured out while not producing enough food.

Bio brochures use nice words about making the world better, and I used to take them by their word, too. Not that I think they treat their workers badly – I hope not. But that doesn’t mean other farmers do either. I have yet to actually see evidence of the making the world better part. Like you say, this is not mysticism. If they could actually show evidence of environmental benefits by measurable things like nutrient loss, yield, and carbon footprint, I would really listen. Notice the big meta-analysis on more nitrogen run-off in my Natural Assumptions piece is specifically done on European bio farming studies.

What differences I have heard about between different labels, are that there may be some additional restrictions on pesticides depending on country, mostly. They all still allow pesticides, and pesticides must by their nature be something poisonous to plants and animals, in order to work. Here the division between ‘synthetic’ and ‘natural’ has never been based on an evaluation of lesser harm. Among the organic approved pesticides in Swiss Bio standards (in appendix 3 among others) are things like plant oils, pyrethrins, and copper. And is there some evidence of them being so much better for the environment? None that I’ve seen.

“The three most common organic herbicides are clove oil, acetic acid (mixed with water it makes vinegar), and cinnamon oil. All three are more toxic than Roundup, which is actually less toxic than table salt. (Click on each for their MSDS.) Organic herbicides only kill the plant tissue that it touches, requiring more to be sprayed, and more repeated spraying.” http://welovegv.com/pesticides

Repeated spraying also means repeated rounds of tractor use (compaction, carbon emissions..).

But all in all, pesticide use is often really skewing the perspective on farming and its environmental impacts. This pesticide-fear is detrimental because there are other really important environmental issues that we should be focusing on instead. See this excellent Food and Farm Discussion Lab post on that:

“When you really dig into the research on the hierarchy of ecological impacts, pesticides represent a drop in the sustainability bucket when compared to land use, water use, pollution and greenhouse gases. In fact, it may seem counter-intuitive but, pesticides can play a substantial role in mitigating the damage associated with many of those other factors. Pesticides allow for us to grow more food on less land, limit the wasting of fuel and water, and help curb erosion and run-off. There is nothing sustainable about pouring inputs into growing food that is destroyed by pests.”

http://fafdl.org/blog/2015/03/06/focus-on-pesticides-is-a-distraction-from-major-eco-impacts/

Bio Suisse says:

“Therefore, it is vitally important to maintain and improve natural soil fertility through appropriate cultivation practices. Anything that detracts from this goal must be avoided. In particular, the use of synthetic fertilizers and synthetic or genetically engineered plant protection products is prohibited.”

So, how does one take care of the soil and its fertility?

From a great piece from an agronomist on what sustainable means:

“1. Protect the soil

2. Maintain soil fertility

3. Use water efficiently

4. Protect the crop”

On nr 1. :

“We must minimize erosion, as that is the greatest threat to the soil. This is the top priority because erosion is not easily fixed. We minimize erosion by protecting the soil surface from wind and rain. Here are the main practices used:

Maintain crop residues. This is the best way to keep the soil protected.

Minimize tillage. Tillage reduces soil cover leaving it more prone to erosion.

Avoid compaction. Fixing compaction requires deep tillage to fix, which increases the potential for erosion.”

And again for 2. Maintain soil fertility (among others, see the piece):

“Reduce erosion. Erosion is the loss of soil, but also of nutrients. Erosion can be reduced by the methods in #1 above.”

http://www.biofortified.org/2015/08/sustaining-agriculture/

And here the goal and the aversion of scientific methods contradict each other. What is best for soil is to avoid tilling (Bio Suisse says as much), but then without further justification they throw the biggest tool allowing no-till out of the window – namely GMO and otherwise created herbicide resistant crops.

Here are some summaries of how the environment benefits from biotechnology: “Shortly put, GMO crops have been found to increase farming efficiency: higher yields, reduced pesticide use, increased profits, and reduced farm labour.

GMOs help farmers make the best possible use of the land area used for farming. Does that mean that they are using the land somehow too efficiently, resulting in drawbacks for the environment? Not really. Farmers continue working their land for generations. What is best for them is a land that stays healthy and soil that retains its nutrients. On top of that, there are good arguments for farm efficiency being a good measure of its impact on climate change. To clarify what efficiency means in practice, I’ll borrow Marc Brazeau’s words over at Genetic Literacy Project:

High yields are an indicator of efficient use of resources. High yields indicate that water, fuel, fertilizer, pesticides, labor, etc were successfully transformed into food instead of weeds, bug food, and run off.

..

and

The US Department of Agriculture notes that the spread of the no-till method is largely thanks to the adoption of Herbicide Tolerant (HT) crop varieties.” More in the piece: https://thoughtscapism.com/2015/03/22/gmos-and-the-environment/

Other pretty awesome things being developed: https://thoughtscapism.com/2015/07/28/three-ways-science-could-improve-the-world-through-rice/

But NO Bio label can or intends to ever use these methods.. because – not natural.

Bio suisse:

“Propagation methods should be as close to nature as possible. … The use of genetically modified source material is prohibited in organic farming. The use of hybrid seed for the cultivation of grain (except maize) is prohibited.”

I am at a loss. I am an environmentalist, and I can’t see why people don’t want evidence of environmental benefits, but instead they would settle for a nice idea of natural with ‘surely it must be better for the environment’.

Even their ‘energy efficiency’ doesn’t say anything apart from ‘let’s not waste heat or lighting’. Nothing about pouring fertilizer, pesticides, tractor hours, irrigation, into producing a lesser yield (more eaten by pests, more runoff) and thus needing more land to make the same yields as farming methods that are optimised looking at the evidence?

If you look at that table on exposingthetruth on environmental costs in farming, it’s very much in line with the paper discussed in the Food and Farm Discussion Lab piece above – the developing countries especially are wasting resources, while the US farming sector has managed to significantly reduce it’s environmental impacts. In no way does it say that organic farming would be better.

It even connects to the big problem in rice cultivation – which GMOs could fix.

Also, it confirms that animal farming is a huge problem. Yet if we were to move to all organic farming, we would need way more cattle to produce all the manure, which is the only allowed form of fertiliser. Organic farming as is now, is dependent on manure from all the conventional cattle manure.

http://environmentalresearchweb.org/cws/article/news/56037

This comment of yours:

“But I will have that any day over mostly profit-driven, industrialized/factory farming with no sense of social responsibility, fair pricing and so on.”

really could have been mine a few year ago – it is very much how I used to assume it was – but after what I’ve learned the past years, I’d just ask you to stop and wonder, is this so? What is industrial/factory farming anyway? Do farmers have no sense of social responsibility of fair pricing? What bad things do they do in order to make a profit, that their bio colleagues aren’t doing?

I know there were several harmful pesticides in the 70s and earlier, and other methods that luckily were abandoned, and other methods, like Integrated pest management, and crop rotations, cover crops, that are luckily being used more nowadays. I know there are improvements that should and can be made, unfortunately I see many of them antagonised and shunned by the organic movement.

And “controversial cases of soy and corn” I wonder what you mean? They are not controversial if you look at the science of it. The popular culture does tend to vilify them though.

You can read more in the report by European Academies Science Advisory Council (ESAC):

Taken together, the published evidence indicates that, if used properly, adoption of these crops can be associated with the following:

• reduced environmental impact of herbicides and insecticides;

• no/reduced tillage production systems with concomitant reduction in soil erosion;

• economic and health benefit at the farm level, particularly to smallholder farmers in developing countries;

• reduction in greenhouse gas emissions from agricultural practices.”

Again from the piece: https://thoughtscapism.com/2015/03/22/gmos-and-the-environment/

What comes to Monsanto, I haven’t read that book, but I have heard so many incredible claims that turn out not to be true when I’ve tried to check them out. This is a good collection of links, might be helpful for double-checking, depending on what claims you may have heard.

http://wiki.skeptiforum.org/wiki/Marc_Brazeau's_Monsanto_is_Not_Evil_Starter_Kit

Thanks for the freiland link, I will definitely check that out! I only eat meat a couple times a month, and I try to make sure it is from a more animal-friendly label. I just love animals, and want to know they have had a comfortable and interesting life, really.

I’m sorry if it’s a bit mangled, and got so long.. please let me know if there’s something I missed to comment on.

I hope you have a good start of your week! Tschüss!

Iida

LikeLike

Hi Iida

Thanks for the wishes! 🙂

And thank you also for taking the time to respond and sharing your sources. I am also extremely happy that I am not the only one interested in the where and how our food comes from and how to optimize that. So many people I’ve talked to _refuse_ to be informed, for fear of having to change their eating habits! It’s driving me nuts.

Anyway, farming has been an extremely important topic for me ever since I can remember. I grew up in the countryside, where absolutely everyone grew their own food and many were also making a living out of selling food. So, I know a thing or two first hand about farming (at least on a smallish scale). I am also very fond of tasty, “real” food. In fact, I only got to know supermarket food when I left home for university. Around that time, I also got interested in agricultural science (or the science of farming, if you prefer) and started reading on it. At that point, I was still unaware of bio agriculture.

Then, in 2008, just before starting my PhD, I read “The World According to Monsanto” (and related sources) and was appalled at all the issues surrounding GMOs (will come back to these later). That’s when I actively started consuming bio food, with the goal of voicing my opposition to GMOs. I also continued to furiously read on the topic. I think I can safely say that I would have finished my PhD in 4 years instead of 6, had I not had such a relentless interest in agricultural and environmental topics.

I also joined all kinds of online communities opposing GMOs and was extremely disappointed to discover that many of them were mostly propagating complete nonsense about GMOs, instead of highlighting the actual problems and the accompanying evidence. These are the same people who make anyone opposing GMOs look like an anti-science loon. But, luckily, science-loving people have an open mind and are able to distinguish between fear-mongering and actual, very serious problems.

I also became skeptical of the bio food I was so eagerly consuming. I had never actually looked at the standard, I just knew that it was guaranteed to be GMO-free. But what if the bio farmers were the same kind of loons I had found in the anti-GMO online communities? So I went and looked at the actual bio standard (Bio Suisse, as I was already living in Switzerland at that point), but found nothing off-putting (please bear with me, will come back to your objections to bio later).

A couple of years later, in 2010, I read “Eating Animals” (and related sources) and was yet again appalled at the practices of large-scale animal husbandry. I became (almost) vegetarian (I still ate animal products from my home village, when I went back). I felt a profound disgust for everyone around me who stuffed themselves with cheap supermarket meat and was completely oblivious to the consequences of their actions! For my research, I had to do a good amount of travelling, mostly to the US. I always spent hours looking for local vegetarian restaurants, ideally also bio, for local bio supermarket and so on. I went to these, despite the long distances or other inconveniences. When I couldn’t find any, I ate just enough to function…

So, all in all, I think I can consider myself quite well-informed on the topic of bio agriculture and agricultural science. I will admit I haven’t had the time to read as much as I used to in the past two years: having a baby and leaving behind the time-flexibility of academia have definitely taken their toll. But I am trying to keep an eye on things and continue interacting with smart, interesting people (hence this discussion with you :)).

The auto-biographical rant is over, the interesting stuff will follow shortly in a separate comment.

LikeLike

P.S. Your original piece on organic farming “Natural Assumptions” seems to be mostly based on references relating to the American organic industry, which is radically different from the Swiss one, this is why I was asking which standard(s) are the actual studies about.

Also, as you may have noticed, some of the points I tried to address above actually appear in “Natural Assumptions”, not in the above.

LikeLike

[I’m putting the reply here, so that it doesn’t get super narrow and less readable.] [THOUGHTSCAPISM(Iida): I’m adding a few answers in line here for clarity so it won’t be too hard to trace the discussions]

I think your reply missed one of the two main points I made in my comment: the fact that it is prohibitively difficult to compare bio agriculture as a whole to conventional agriculture as a whole (if that exists). The final conclusion can only be a personal opinion, no matter how long and how solid the accompanying list of supporting studies. (The second main point was related to Bio Suisse and its particularities, on which you have commented.)

For you, the perception that bio agriculture is anti-science is a deal breaker. I disagree with this perception on the whole, although I can agree with a few of the individual points that contributed to it (more on these below).

For me, the problems of conventional agriculture (list below) far outweigh its higher willingness to adopt bleeding-edge methods and technology.

Before going once more through your list of objections to bio, let me once again state the reasons why bio is important to me, in order of decreasing importance:

1. environmental sustainability

2. minimized adverse effects on health

3. taste, aspect and diversity

And now to (some of) your objections. Just for overview, to keep some order:

— origin of bio agriculture

— lack of justification for using natural methods

— pesticide use

— GMOs

— profit, social responsibility, pricing.

Origin of bio agriculture.

So the “biodynamic movement” may have given the starting impulse to present day bio agriculture. So what? I see no warning sign in that. Just as I see no warning in the fact that medicine at some point included the practice of blood-letting and “barber-surgeons” as medical practitioners, or that people were recommended to avoid bathing as a disease prevention strategy, or that (some) pediatricians endorsed “crying-it-out” at some point. I could go on, but I hope you see the point.

Mind you, the team of guys who came right after Steiner (Mueller & wife, Rusch, etc) and were much more influential on bio (as opposed to Demeter-biodynamic) were a biology teacher (Mueller), a doctor (Rusch) and a microbiologist (Becker). They laid a scientific basis (at the time) of bio agriculture, based on their work on the lifecycles and functions of bacteria (published in an article called “The Cycle of Bacteria as Life Principle”). The work has apparently also recently (2009) been revisited: literatur.ti.bund.de/digbib_extern/bitv/dk042577.pdf (in German).

Going back to Steiner, yes, he seems to have been crazy. But he also pretty self-deprecating and told people verify what he was recommending empirically, as he hadn’t tested anything and had no clue about agriculture…

Finally, as an aside for your information, one of your links on biodynamic actually supports bio 😛 (https://biodynamicshoax.wordpress.com/ — A small box on the right sidebar: “This blog is about biodynamic viticulture. It is not an attack on organic or sustainable farming—both of which the author supports.”)

[THOUGHTSCAPISM (Iida): I’m adding a few answers in line here for clarity. The worrying thing with biodynamic farming is that organic farming is how close it still is the more mystical practices like biodynamic. It’s evident here, for instance, where I look at the UN report on organic: https://thoughtscapism.com/2015/09/21/myth-un-calls-for-small-scale-organic-farming/ which includes Steiner/biodynamic organisation in the mix. The page about biodynamic is useful for giving an idea what biodynamic is about. Whether its writer supports organic or not, is unfortunately not evidence for benefits or drawbacks of organic. I used to support organic too, but sadly that was not because I had properly looked into the evidence.]

Lack of justification for using natural methods.

Personally, I see lots of issues with both GMOs (in their current form) and pesticides — that is justification. I believe it is every person’s responsibility to check what they are eating, and whether the way it is produced makes sense or not. One could just as well argue that it is irresponsible of conventional agriculture to use GMOs and pesticides, without justification and without solutions for the problems created by them. [THOUGHTSCAPISM(Iida): this would be an important point to consider giving sources to claims, so that we know what problems you mean, and how they are not being handled responsibly, and how that has to do with the methods themselves]

Natural methods have been refined and have proved their worth over at least a thousand years. Sure, they don’t work in the context of the industrial-scale farm. But is that really such a bad thing? Are industrial-farms the way to the future? Not according to the UNCTAD Trade and Environment Report 2013 (http://unctad.org/en/Pages/Publications/TradeandEnvironmentReviewSeries.aspx). It suggests moving away from current industrialized farming to small-scale farming and to a “holistic”, integrated approach, where it is finally recognized that everything is connected to everything. You cannot optimize for one factor here (let’s say yield) and expect everything everywhere else to stay unchanged. In the same vein, it calls for a fair comparison between “single climate-friendly practices” (like the ones you argue for) versus “systemic changes” (like bio agriculture among others).

[THOUGHTSCAPISM(Iida): This UNCTAD report has come up so many times in discussions that I decided to write a whole post about it: https://thoughtscapism.com/2015/09/21/myth-un-calls-for-small-scale-organic-farming/ This report does not represent UN’s views, it’s authors feature many advocacy groups/companies, and there are some rather worrying choices among it’s writers. Note official UN view actually underlines that GMOs and biotech should be included in farming methods.]

This is also exactly the point of my first comment to your article, which I have apparently failed to express properly. You can hardly compare the individual optimizations of conventional agriculture to the approach of holistic optimization that bio agriculture is taking. If you have ever in your research work dealt with systems’ optimization in general (regardless of research field), you should see this point right away.

Incidentally, the Bio Suisse standard also has specific provisions for encouraging self-sufficient (or almost) small-scale farms, where natural cycles are not broken (e.g. manure going back to the soil as fertilizer for plants), where crop rotation is almost mandatory and so on. The highly specialized focus of industrial farming makes it impossible to balance out activities and their results (e.g. overproduction of a certain product or extremely high quantities of waste, that are very hard to deal with — like the manure from factory-farms, and so on).

Side note: I have said this before, maybe not clearly enough: as far as I know, animal farming is currently producing a large and problematic surplus of manure currently. There is no way we would need to grow more cows in order to sustain more bio agriculture (this would also not be in line with the mentioned holistic approach to agriculture that bio is following).

[THOUGHTSCAPISM(Iida): Again important not to assume. Did you read the citation I gave before? http://environmentalresearchweb.org/cws/article/news/56037 – organic as it is now is largely dependant on conventionally kept animal’s manure. Organic cattle just isn’t sufficient for the amounts of manure needed. The Federation of Swedish Farmers has even calculated that for the whole of Sweden to go organic – as the Green party calls for – they would need 3 million cows – an increase by 10 times compared to what the whole of Sweden has as is. (source in swedish, but can look for if they have it in English)]

Pesticide Use

Many pesticide are toxic way above and beyond the targeted pest. You may be familiar with the issues surrounding the dramatic decline of the bee population and how it’s very likely caused by synthetic pesticides. Other species are in a similar situation, though they don’t have as high a profile as bees (butterflies, small birds etc).

[THOUGHTSCAPISM(Iida): actually the confirmed reason for the recurring cycle of Colony Collapse Disorder has been known for some time to be the Varroa Mite. The bee populations have already bounced back again, also countries that do use neonics like Australia, didn’t have problems with their bees – because they don’t have the mite. The pesticides neonicotinoids helped substitute were more toxic to bees and other insects than neonicotinoids, which for sure are toxic to insects (insecticides..), but the realistic exposure is very little. There is lot of important research to follow on neonics, and it is also not a topic where one should rely on assumptions. I’m adding more reading in a separate new comment on this one. I’ll add info on the butterflies there too – not a casualty of pesticides or GMOs.]

The three most common organic pesticides you cite (btw, your link – http://welovegv.com/pesticides – is broken) seem to break down fast and leave little behind. Synthetic pesticides, on the other hand, tend to persist in the environement and to accumulate in relatively large quantities in the fatty tissues of various animals, especially fish (and including humans).

I have nothing against (synthetic) pesticides, but with the current issues still lingering, I think it is perfectly justified to exclude them from bio agriculture. [Big assumptions here. DDT accumulated in fatty tissues, and ever since the 70’s great care has been taken to use pesticides that do *not* bioaccumulate. Could you give a citation to one in use?]

GMOs

I have several bones to pick with GMOs:

— patenting of genes/seeds (I know GMOs are not the only patented ones, I support none)

— threat to biodiversity through cross-contamination and extreme competition

— huge pressure and ultimate destruction of small farms through monopoly

All this is nicely discussed in a very interesting MIT (Dept. of Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences) class called Mission 2017: http://12.000.scripts.mit.edu/mission2017/genetically-modified-crops/

I like it a lot because it is a very balanced treatment of GMOs, highlighting both the huge potential of GMOs as well as their equally big current problems. As you may know, this is extremely difficult to come across.

In short, I can only restate what I said in the previous comment: I am absolutely not against biotechnology and I am willing to accept your claims of improvement brought by GMOs in individual areas. I just cannot possibly support the current format of using GMOs. Hence, I also think it is justified for bio agriculture to reject it (for the moment).

[THOUGHTSCAPISM (Iida): Patents are universal for organic, conventional, biotech. Not a GMO issue. Threat to biodiversity? No references given. There is no known ‘outcompeting other plants’ that I know of that has actually happened. Food crops (most, whichever category) tend not to compete well (or even survive long) in nature unless they are specially taken care of – they have been bred for characteristics that are useful for us, like lot of energy poured into producing high yield. Cross contamination happens with crops made by all methods. Does not ‘lead to monoculture’. Mangles concepts here. No references given. This is a site by a group of MIT students. It might be useful to find more scientific / professional agricultural sources. Continue later, have to run now… have a great day!]

Profit, social responsibility, pricing.

As I pointed out before, these are an integral part of the Bio Suisse standard (btw, I believe the link I sent you is not a mere “brochure”, it is the actual standard to which the farms are held for certification).

These issues also appear time and again in UN reports (like the one I cited above) under “problems with the current industrialized agricultural system”. They are also discussed in the context of GMOs in the Mission 2017 class. Also, if you read the “Eating Animals” book, you will find out a lot more unpleasant details about what the idea of social responsibility and fair pricing/salaries represents for factory farms.

So yes, bio agriculture also needs to make profit in order to survive. But the mentioned provisions for social responsibility, fair pricing etc, as well as the focus on small scale farms, put it in a whole different league compared to industrial agriculture.

And this brings me to the end of my case (though I certainly cannot have covered everything relevant). There remain two footnotes:

On reconsidering my views of Monsanto.

I took a quick look at Marc Brazeau’s starter kit. I have not discovered any new information in there.

— I still disapprove of seed patents — Hawaiian papaya is the proof that GMOs work just fine without them as well. Also, enforcing seed patents on contaminated crops is beyond outrageous, as far as I’m concerned (also discussed in Mission 2017).

— I disapprove of the interdiction to save seeds for the following year.

— I am not familiar with all the trial cases, but I know the one of Percy Schmeiser. It touches exactly the issues of enforcing a patent on contaminated crops and of saving seeds. In my opinion, he should have won.

— There is no mention of the shady business of “substantial equivalence”, which meant that the safety for consumption of GMOs was initially not even tested, if the company could show that the new plant/organism is “equivalent in substance” (a completely meaningless expression) to the conventional version.

— Finally, even Marc Brazeau concedes that Monsanto has shady legal practices to say the least. In the book I recommended, there is ample information on that.

As far as I’m concerned, anyone believing that any corporation the size of Monsanto has the best interest of humanity and/or the environement at heart is incredibly naive at best.

On the standing of science.

Science is great and has helped accomplish almost everything we are enjoying today. However, modern day science is also deeply flawed. The biggest and well-known problem is the lack of reproducibility of studies. The amount of data or experiment setups that are made publicly available so that anyone can re-do the experiment and check the results is ridiculously small. Many studies declare that the “data is available upon request” and when you request it, there’s zero response.

Another issue is the peer review process, where reviewers volunteer from their already limited time and often produce very superficial and/or biased reviews, based on knowing the author or recognizing them implicitly from the article.

So, scientific studies are definitely not above and beyond all doubt.

Have a good week too!

A.

LikeLike

Hello again Andreea!

I’m happy that you are eager to discuss this topic. I do worry, however, that when there are so many topics up at once, some threads may get mingled and it won’t be easy for us to follow each issue clearly. It might be easier even to have this discussion at a discussion forum – say, Food and Farm Discussion Lab (https://www.facebook.com/groups/FAFDL/) or GMO Skepti-Forum (https://www.facebook.com/groups/GMOSF/ – you can get an idea about the discussions from their archived threads at a wiki here: http://wiki.skeptiforum.org/wiki/GMO_Skepti-Forum_Threads), with many farmers and scientists able to participate in the conversation. If you’d rather just continue here, I am happy to thoroughly discuss each and every one your points. But I hope you also find it a good idea to do that one at a time rather than all at once?

Maybe we should start with the most important one. You can choose – or I am thinking that maybe you would agree that it is this one: environmental sustainability – or the environmental impacts from farming. This is my main reason to stop buying organic labels, too. The deal-breaker. So we seem to have arrived at different conclusions on the question. So a good starting point would be: how can we look at the evidence together to reach one conclusion or the other?

How could we find out if organic (or specificaly Bio Suisse organic if you wish) is the better choice for environment than non-bio food? I am not sure what you mean exactly with your comment about not being able to compare different agricultural methods as a whole. Maybe you can elaborate? I’d believe that you think organic can be compared to conventional in some way, though, else how could you arrive at any conclusion of it being better?

Let me know which discussion format you would prefer!

Hope you are enjoying your day 🙂

Iida

LikeLike

Hi Iida

Feel free to move the discussion wherever you please. I am anyway not familiar with any of the proposals and I unfortunately also cannot take the time at the moment to check them out properly. This is also why I am still replying here.

I agree the main point is about the sustainability of farming (which for me includes also the issues of fair pricing, social responsibility etc). However, bio versus conventional is not the only dimension. There is also the matter of scale, i.e. industrial vs. “family-farm”. While bio is more often associated with the family-farm scale, they are not synonymous.

On comparing the bio as a whole vs. conventional as a whole: I tried to explain this better in the section on “Lack of justification for natural methods” of my previous post.

Basically, the UN report I linked to expresses it best: it is like comparing “single climate-friendly practices” (which conventional industrial agriculture is going for) versus “systemic changes” (which bio is going for).

If you have ever in your research work dealt with systems’ optimization in general (regardless of research field), you should see that it is very difficult (if not impossible) to compare the individual optimizations of conventional agriculture to the approach of holistic optimization that bio agriculture is taking.

My conclusion of bio being better is in part based exactly on the fact that it is going for systemic rather than individual optimizations…

Cheers

Andreea

LikeLike

Hello Andreea!

So, how can you show that bio but not conventional ag is going for systemic optimisations? I think you are making quite a leap there. Could you elaborate?

Cheers

Iida

LikeLike

From a mathematical point of view, what utility function are you trying to optimize with “holistic optimization that bio agriculture is taking.”?

LikeLike

Sorry for my shortness – before I get to bed, let me elaborate 🙂

See, the problem is that there are a lot of scientists who have taken care to look at several factors, all that goes into the concept sustainable – ‘holistic’ approach if you will. And they haven’t been able to confirm organic as more sustainable, actually the opposite. For us to say anything about them, these factors need some evidence behind them. Saying that ‘social aspects’ are reason that bio is better does not get far, unless we actually have evidence that it has any impact on social factors. If you have any evidence on any of the factors that bio might be better for, I would very much love to know. I have been looking.

There is a great thread on what sustainability means and how it can be studied here: https://www.facebook.com/groups/GMOSF/permalink/477782085694380/

You must join the group to view it though. Maybe I can post some resources to begin with.

Swedish agronomy professors have written a book on this topic, for instance:

“Many people believe that organic agriculture is a solution for various problems related to food production. Organic agriculture is supposed to produce healthier products, does not pollute the environment, improves the fertility of soils, saves fossil fuels and enables high biodiversity.

This book has been written to provide scientifically based information on organic agriculture such as crop yields, food safety, nutrient use efficiency, leaching, long-term sustainability, greenhouse gas emissions and energy aspects. A number of scientists working with questions related to organic agriculture were invited to present the most recent research and to address critical issues. An unbiased selection of literature, facts rather than standpoints, and scientifically-based examinations instead of wishful thinking will help the reader be aware of difficulties involved with organic agriculture.

Organic agriculture, which originates from philosophies of nature, has often outlined key goals to reach long-term sustainability but practical solutions are lacking. The central tasks of agriculture – to produce sufficient food of high quality without harmful effects on the environment – seem to be difficult to achieve through exclusively applying organic principles ruling out many valuable possibilities and solutions.”

http://www.springer.com/de/book/9781402093159

Also, a comment from another member with a very relevant source: “Assessment of agricultural sustainability”

Click to access 439.pdf

the comment

“basically there have been a number of “frameworks” for trying to come up with some sort of sustainability index, and they start to get pretty complicated when you include socio-economic indices.