There is a claim that keeps coming up in  discussions, namely, that one commonly used pesticide class would be the Number One enemy of bees. Unfortunately, deciding that neonicotinoids would be the root cause of bee problems, is a strategy that does not give the bees much cause to celebrate. The evidence points to a whole host of different factors as the main cause for their troubles – mainly mites, viruses, and habitat loss.

discussions, namely, that one commonly used pesticide class would be the Number One enemy of bees. Unfortunately, deciding that neonicotinoids would be the root cause of bee problems, is a strategy that does not give the bees much cause to celebrate. The evidence points to a whole host of different factors as the main cause for their troubles – mainly mites, viruses, and habitat loss.

Meanwhile, removing neonicotinoids would likely add to the environmental burden of farming. NOTE: Piece Updated with recent research in March 2017, particularly with the new sections: New studies on neonicotinoids and Recent studies confirm, honey bee-diseases and habitat loss cause problems for wild bees, as well as some new data on CCD and bee losses under Why is Bee Colony Collapse happening?

We are many, and we need a lot of food. It’s the act of farming itself (that is, our wish to be fed) that brings this difficult balancing act of providing for us while reducing the impacts on the environment. What we do and the space we take up does greatly affect the environment. It’s a difficult problem, and it calls for sophisticated, carefully analysed solutions, not for simple slogans.

We need to grow food. People want to eat that food themselves, instead of allowing it to become food for bugs, and that has implications for the bugs. All insecticides are by definition harmful for insects. It is important to know if innocent bystander insects are significantly harmed by the use of pesticides, and to have steps taken to reduce those impacts. Demonising one class of pesticides without conclusive evidence, in the meantime, is not going to be helpful.

It doesn’t matter what label you slap on the pesticides: organic, ‘natural’, or synthetic – as this recently published paper points out, organic pesticides are also toxic to bees:

Our results demonstrate the potential acute toxicity and sublethal effects of botanical insecticides on honey bees and, thereby, provide evidence of the importance of assessing the risks of the side effects of biopesticides, often touted as environmentally friendly, to nontarget organisms such as pollinators.

But this study, just like many on neonicotinoids, have some major shortcomings, as outlined here by the American Council on Science and Health. Their experimental settings (such as dosage, treatment conditions) do not reflect reality and they cannot actually address the question if these pesticides, under realistic field conditions, will have any significant effect on bee health.

Any insecticide that is used widely will have the potential to cause harm to beneficial insects. We need to know which and to what actual extent. Just showing that an insecticide under right conditions (high dose, administered directly) is able to harm an insect is not enough (in fact it’s a tautology).

A lot of pesticide residues can be found in bee colonies. What role any of them might play in bee health is not clear, other than it seems likely it isn’t very large. An excellent review of this can be found at BioFortified written by the entomologist Joe Ballenger:

“A lot of pesticides are found in honeybee colonies and based on pesticide survey data the USDA actually suggests that pyrethroid insecticides are a higher risk to honeybee colonies than are neonicotinoids.”

“Neonicotinoids are a small subsection of the pesticide story. Pesticides are a very small part of the CCD story, and are a small part of the overall honeybee health story.”

For nature’s as well as our own best interest, we should always take into account the total harm vs benefits of each farming method and rely on accurate data on its effects.

One new study looks at 42 pesticides (and even one herbicide, glyphosate) to determine if they would be harmful if the pesticides were sprayed directly on the bees in common usage concentrations. Note that this scenario applies to the (rare) situation of spraying a flowering crop with ongoing pollination, in the daytime – something that any farmer depending on pollinators would be sure to avoid (and which neonicotinoid labels directs against). However it illustrates the point that demonising one class of pesticides is misleading at best:

Using a modified spray tower to simulate field spray conditions, the researchers found that 26 pesticides, including many (but not all) neonicotinoids, organophosphates, and pyrethroids killed nearly all of the bees that came into contact with the test pesticide sprays. However, seven pesticides, including glyphosate and one neonicotinoid (acetamiprid), killed practically no bees in the tests.

While neonicotinoids are far from the monsters that some sources make them out to be, and most likely a better choice than the pesticides they replaced, some of them can cause harmful effects for bees. To what extent, in which situations, and to which bees is important to establish before we fool ourselves into thinking that we already know the best course of action. The current practices already in place greatly limit bee exposure to pesticides. In some cases dry and windy conditions have caused planting dust from pesticide-treated seeds to inflict great harm to local bee colonies, and German research paper from 2013 suggests mitigating strategies for this:

The total quantity of abraded dust as well as the actual emission of dust during the sowing operation can be significantly reduced by technical means (e.g. coating recipe and facility equipment, deflector technology) and by additional mitigation measures (e.g. maximum wind speed).

In addition to that, there are voluntary coordination and mapping projects (like Fieldwatch Indiana) that help farmers and beekeepers keep bees out of harms way.

New studies on neonicotinoids

In 2016, a couple of studies on neonicotinoids caught the public eye. One, published in Nature, looked at long-term effects in variety of bees – excluding honey and bumble bees. It looks at the situation of these bees during a period of increase in intensive oil-seed rape farming in the UK. The authors found 20 % declines near rape fields, and they say neonicotinoids could have a role in that decline, suggesting about half of the total impact, although they admit their study has no way of determining the definitive causes (they only look at correlations). A BBC article, despite a quite a a click-baity headline, does rather a good job of analyzing the paper. It aptly points out that you can’t grow oil-seed rape without pesticides. There might be some effects on (non honey-, non-bumble) bee numbers from pesticide use on oil-seed rape, but this might also be due to factors like habitat loss and increasing farming of one crop type. If neonicotinoids are banned, however, a shift to older types of pesticides may well result in more harmful effects for bees, not less.

Another 2016 study, from Washington State University, looked at the concentrations of neonicotinoids found in the field. The trace amounts they detected were so low as to warrant no reason for concern, as they were much lower than doses shown to cause any effects in bees. Perhaps farming practices differ enough so that some areas would regularly see higher residues in pollen, and there could be more notable effects, enough to cause a few percent decrease in bee populations – like part of the decrease observed in the UK study. The WSU study found:

Throughout the one-year trial, neonicotinoid residues were detected in fewer than five percent of apiaries in rural and urban landscapes. Two neonicotinoids, clothianidin and thiamethoxam, were found in about 50 percent of apiaries in agricultural landscapes.

Although neonicotinoid insecticide residues were detectable, the amounts were substantially smaller than levels shown in other studies to not have effects on honey bee colonies. The WSU researchers referenced 13 studies to identify no observable adverse effect concentrations for bee populations, which they used to perform a risk assessment based on detected residues.

“Based on residues we found in apiaries around Washington state, our results suggest no risk of harmful effects in rural and urban landscapes and arguably very low risks from exposure in agricultural landscapes,” Felsot said.

For a look at even newer research (June 2017), please see the separate post: New Study Finds Neonicotinoids May Have Harmful, Beneficial, or No Effects on Bees.

Bee health is complex

If you look at reviews over bee health, the influencing factors belong to many categories, many of them interconnected (as an example, weather can influence food supply which can be mitigated by management). While it is difficult to weigh the importance of each category in each situation, one thing is clear from all these sources: parasites and disease are the number one threat to bees. I’ve made a graphical presentation to illustrate the factors with this emphasis. Neonicotinoids are but a small part of the pesticide picture, and pesticides are but a small part of overall bee health picture.

Sources listed in full below

USDA lists Pathogens, Parasites, Management stressors, and Environmental stressors – this last category contains the categories I’ve separated above into Climate, Nutrition, and Pesticides. Croplife similarly divides the threats as follows: Pests and disease, Food supply, Climate and Weather, Pesticides, Beekeeping practices. A 2010 US survey of beekeepers lists factors that beekeepers have deemed influential in bee losses, and organises them roughly in the order of decreasing weight as follows: Starvation, Weather, Weak (hive) in fall, Mites, Queen, CCD, Nosema, Pesticides. They conclude:

Manageable conditions, such as starvation and a weak condition in the fall were the leading self-identified causes of mortality as reported by all beekeepers.

The German 2010 review paper Emerging and re-emerging viruses of the honey bee (Apis mellifera L.) highlights the impact of the spread of viruses by Varroa destructor and increased virulence of several bee viruses, and underlines the role of the mite together with Deformed Wing Virus (DWV):

DWV in V. destructor infested colonies is now considered as one of the key players of the final collapse.

The paper offers approaches for combating bee viral diseases such as selection of tolerant bees, RNA interference and prevention of new pathogen introduction.

Update: For some good news about finding a cure, you can read this thoughtful piece about a well-known bee scientist who joined Monsanto in order to try to create an RNAi cure for the Varroa Destructor mite. He was the one to witness one of the earliest sudden bee colony deaths ten years ago, and helped coin the term colony collapse disorder. Unfortunately, new five-year -study finds varroa mite and viruses to be spread even more widely than assumed earlier, as reported by Science Daily:

Key findings show that the varroa mite, a major honey bee pest, is far more abundant than previous estimates indicated and is closely linked to several damaging viruses. Also, the results show that the previously rare Chronic Bee Paralysis Virus has skyrocketed in prevalence since it was first detected by the survey in 2010.

Another study from 2016 supports the view that the spread of these diseases is largely man-made – commercial honey bee trade emanating from Europe is largely responsible for the spread of varroa and deformed Wing Virus.

Why is bee Colony Collapse happening?

This is the handiwork of U.S. Geological Survey Bee Inventory and Monitoring Lab

Looking up all the resources I’ve read every time this topic comes up is tedious. Instead, here I’ll provide a list of quotes and links that hopefully give a useful gateway for those who are looking to read more in-depth from evidence-based sources about bee health.

What comes to Colony Collapse Disorder (CCD), its cause has by no means been traced back to pesticides. It may be that pesticides play a small role, but parasites like Varroa mite and flowerless landscapes seem to be the main factor there, not the pesticides. Neonicotinoids are also used in areas with no CCD, like in Australia. Australia, however, doesn’t have the Varroa mite, which “remains the single most detrimental pest of honey bees” according to USDA:

“Since the 1980s, honey bees and beekeepers have had to deal with a host of new pathogens from deformed wing virus to nosema fungi, new parasites such as Varroa mites, pests like small hive beetles, nutrition problems from lack of diversity or availability in pollen and nectar sources, and possible sublethal effects of pesticides. These problems, many of which honey bees might be able to survive if each were the only one, are often hitting in a wide variety of combinations, and weakening and killing honey bee colonies. CCD may even be a result of a combination of two or more of these factors and not necessarily the same factors in the same order in every instance.”

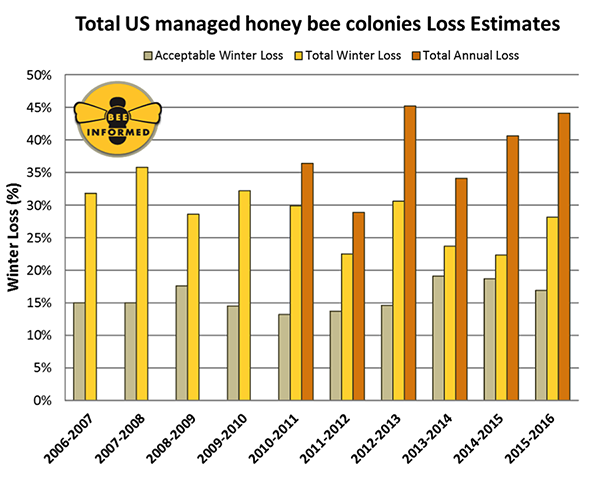

While discussion about definition of CCD, and which kind of losses constitute CCD, can be complex, the fact remains that honey bee losses have remained higher than usual – according to the USDA, before Varroa epidemics over-winter losses were 10-15% each year, and between 2007-2012 they were still 22-33%. Managed bee populations are able to compensate for these losses, split hives more often, buy more queens and bees when necessary, and honey production is not in danger.

However, the summer losses are high as well, as documented by the bee-informed survey (funded by the USDA), highlighting that there are significant problems facing bees still, and their piece points first and foremost to the problem with varroa mites, noting also the problem of hobby beekeepers who may not know how to correctly stop their spread (or choose not to – see more in: ‘Treatment-free’ Beekeepers Give Varroa Mite Free Rein).

Many claim that bees are not troubled at all, and that hive numbers are up, implying that all bee problems are behind us. But it is important to keep in mind that relying on hive numbers, instead of percent losses, or actual bee numbers, is a misleading statistic. Splitting a hive in two and buying a new queen does not have to be a sign of true improvement in bee health or numbers. The Mad Virologist has written more about that in Misusing definitions is not the way to counter misinformation. The honey bee industry is coping with the situation, but the problems are real and in need of solutions.

Many claim that bees are not troubled at all, and that hive numbers are up, implying that all bee problems are behind us. But it is important to keep in mind that relying on hive numbers, instead of percent losses, or actual bee numbers, is a misleading statistic. Splitting a hive in two and buying a new queen does not have to be a sign of true improvement in bee health or numbers. The Mad Virologist has written more about that in Misusing definitions is not the way to counter misinformation. The honey bee industry is coping with the situation, but the problems are real and in need of solutions.

Additional reading on neonicotinoids and CCD

For a scientific beekeepers perspective, read here:

“Some readers may wonder why I am spending so much time on the issue of pesticides, since to many (if not most) beekeepers, pesticides are a non issue. In answer, the main reason is that the public (and our lawmakers) are being hammered by the twin messages that the honey bee is on the verge of extinction, and that the reason is pesticides. In my writings, I’m attempting to address the validity of both of those claims. ”

http://scientificbeekeeping.com/sick-bees-part-18f7-colony-collapse-revisited-pesticide-exposure/

Another synthesis from a chemists’ perspective here:

“In conclusion, the evidence implicating neonicotinoid pesticides as being a major player in the collapse of bee colonies is still far from conclusive, but there are legitimate concerns. There’s certainly an argument that we should do all we can to preserve pollinator populations – after all, we’re reliant on either direct or indirect insect pollination for the success of a significant proportion of our food crops worldwide. Still, other potential causes of bee decline have to be identified and tackled too, and a ban on neonicotinoids alone is unlikely to prove the pivotal change that turns around bees’ fortunes.”

Another piece from the Genetic Literacy Project on this topic here (note, however, that they rely on the misleading statistic of hive-numbers to gloss over continued bee-losses and imply bees are not in trouble):

“Large-scale field studies – four in Canada, one in the UK, four in Europe, most done under Good Lab Practices — have reached the same conclusion: there is no observable adverse effect on bees at the colony level from field-realistic exposure to neonicotinoid-treated crops.

[…] Almost all of the research that suggest that neonics harm bees are in artificial environments or laboratory ‘caged-bee’ studies that have been demonstrated to greatly overdose bees.”

What about bumblebees?

This is the handiwork of U.S. Geological Survey Bee Inventory and Monitoring Lab

I recently read about research implying that wild bees, especially bumble-bees, would be more affected by neonicotinoids, and that many bumblebee species would be threatened. More about the study here.

Interestingly, taking a more careful look at the status of wild bees reveals that for a great majority of species, no population data exists. The chief for U.S. Geological Survey Bee Inventory and Monitoring Lab, Sam Droege estimates there to be 4,000 bee species north of Mexico, with about 400 which don’t even have a name. Check out his beautiful photos of bees, too, in this piece in Slate.

A paper published in Nature 2015 concludes that only a small subset of wild bees (2 %) are visitors and pollinators of crop species – this subset would be most exposed to pesticides. However, these species are not among the threatened wild bee species (see study in Nature).

For the bumblebees where observations have been made, data supporting a decline exists for just a few percent of the cases, and there it points to a similar picture as for the commercial honeybees. Here from a Status Review from The Xerces Society for invertebrate conservation (my epmhasis):

…several lines of evidence implicate introduced disease as the most likely cause of the declines of Bombus sensu stricto in North America.

It turns out that the pests troubling commercial Europen honeybees – an introduced species in the US – are also spreading into wild bee populations, causing decline in those most susceptible to the disease. One of these is the already mentioned Varroa mite infestation. Other bumblebee diseases that seem to be honeybee-derived are Deformed Wing Virus and the parasite Nosema cerenae, as reported in Nature in 2014.

A number of bumblebee species may be in decline, but there is so far no clear indication of a widespread threat, considering that the status of so many species is unknown and little tracking data exists. Quote from a paper in the Kansas Entomological society:

Clearly, most eastern North American bee species have persisted until recent times, with no evidence of widespread recent extinctions.

UPDATE: recent studies confirm, honey bee-diseases and habitat loss cause problems for wild bees

As we learn more about the (largely unknown) situation of wild bees, it seems clear that many of them are threatened. A lot of attention was given to the enlisting in US of seven bee-species as endangered. The reasons for the threat, as outlined by NPR:

…habitat destruction because of urbanization or nonnative animals, the introduction of nonnative plant species, wildfires, nonnative predators and natural events such as hurricanes, tsunamis and drought.

And there is increasing concern that wild bees are in fact taking a hit thanks to competition and, most of all, disease epidemics spread by commercial honey bee populations. You can read more about it at InsideScience, How the Bees You Know are Killing the Bees You Don’t:

…the leading suspect in their disappearance is disease spread by other bees — commercial bumblebees raised by humans to pollinate crops.

It is important to note that one important factor is habitat loss – so if you would like to help the bees, don’t start a honey-bee hive, instead plant flowers and help create more natural habitat for all bees.

Are bees more threatened than other species?

Looking at the numbers for the native continent of managed honeybees, a report by European Commission, which also notes that status is unknown for 80 % of wild bee species, but finds that nine percent of wild bees are threatened, and that further five percent of species are nearly threatened. They contrast this with findings among other animal categories, which unfortunately reminds us of the fact that many species are squeezed in rather tight in their fight for habitat among dense human population:

By comparison, of groups that were comprehensively assessed in Europe, 59% of freshwater molluscs, 40% of freshwater fishes, 23% of amphibians, 20% of reptiles, 17% of mammals, 16% of dragonflies, 13% of birds, 9% of butterflies and 8% of aquatic plants are threatened (IUCN 2011a, BirdLife International 2004). Additional European Red Lists assessing only a selection of species showed that 22% of terrestrial molluscs, 16% of crop wild relatives, 15% of saproxylic beetles and 2% of medicinal plants are also threatened (IUCN 2011a, Allen et al. 2014).

It is important to know if innocent bystander insects are significantly harmed by the use of pesticides, and to have steps taken to reduce those impacts – which to a great extent is already being done, including labels with directions about protecting pollinators, and information sites like Pesticide Environmental Stewardship. Pesticides are usually applied before flowering (for many reasons), early in the morning or late in the evening, and in ways that minimise dust and drift-off to any areas with actively foraging bees.

Demonising one class of pesticides, in the meantime, is not going to be helpful – the alternatives that are left if neonicotinoids are removed are most likely not better for bees. Neonicotinoids are much more targeted than older, broad spectrum, pesticides. The focus should be on what will likely have the greatest effect on bee health, disease and habitat destruction being among the top concerns.

The big picture

The most environmentally friendly form of farming is one that maximises yields – so that more natural habitat can remain outside of farmed areas – while minimising water use and waste – like nitrogen leeching and greenhouse gas emissions.

There are so many people on this planet that we are pushing on many natural habitats, with serious consequences to all plant and animal life. For the most environmentally friendly farming, smart pesticide use is actually an important tool. Pesticides are helping us minimise total impact on the environment and reduce farming acreage. Focus on pesticides is a distraction from major eco impacts, Food and Farm Discussion Lab:

“When you really dig into the research on the hierarchy of ecological impacts, pesticides represent a drop in the sustainability bucket when compared to land use, water use, pollution and greenhouse gases. In fact, it may seem counter-intuitive but, pesticides can play a substantial role in mitigating the damage associated with many of those other factors. Pesticides allow for us to grow more food on less land, limit the wasting of fuel and water, and help curb erosion and run-off. There is nothing sustainable about pouring inputs into growing food that is destroyed by pests.”

For a closer look at a worrisome trend among hobby beekeepers, read: ‘Treatment-free’ Beekeepers Give Varroa Mite Free Rein. If you would like to have a discussion in the comments below, please take note of my Commenting policy. In a nutshell:

- Be respectful.

- Back up your claims with evidence.

Could you comment on what seems to be greatly reduced numbers of bees overall after two very harsh winters in the Northeast. I didn’t see bumble bees this year until my sedum started flowering in late summer. Does winter normally kill off a small percentage of bees anyway? Thanks.

LikeLike

This is my understanding – honeybees at least have a 10-15% ‘normal’ over-winter loss. If your local bumblebees were among the ones more susceptible to the new pests and viruses, then the losses may be a lot greater, as more than a third of the bees dying over winter has been observed for commercial bees, and these insects are usually well taken care of (for instance given supplemental nutrition if need be).

LikeLike

Great piece

LikeLike

A pragmatic piece. Thank you.

LikeLike

Thank you for this article!

LikeLike

To be fair, they are not demonizing one specific class of pesticide. This is the Pesticide the NGO’s have a chance to ban and make it stick, may I add, based on pure emotion. (It fits so well with the phobia of Cigarettes/Nicotine) If they succeed they will demonize all synthetic pesticides based on more emotions. Dow Agro had Quebec back down to claims of 2,4-D dangers in a Canadian court of law using Science. They still banned the pesticide for home use. Josette Wier and WCEL claims of glyphosate dangers were dismissed in a Canadian court of law using Science. They are banning roundup now.

Nobody cares about ORGANIC Neem Oil (Azadirachtin) killing the Bees. TreeAzin the systemic pesticide for Gypsy Moth, Borer Control was not even looked at yet record numbers of ASH trees in Ontario were injected with it. Bees feed on Tree Sap.

The Bees would recover quicker if we banned organizations like NRDC, David Suzuki, Environmental Defense, GreenPeace, Ontario Nature, RNAO, EcoJustice.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think we all want something we can point a finger at to blame and work on to fix. I do feel when I read forums and see comments by beekeepers that they dismiss the idea that neocotinoids are not that thing. I often see dismissal of work done by anyone who has received any funding by companies who actually have money to support funding in research they care about, like Bayer and Monsanto or the government. I think that the feeling is that there will be undue influence or swaying of the results because of the funding. That may be the case some of the time but science does not hold up to scrutiny and show repeatability when that happens. I find it frustrating that this information is often dismissed out of hand without consideration. I appreciate your article here as it feels like a realistic and even handed discussion of the issue at hand. I most appreciate the commentary about the reality that pesticides are needed to fulfill the food requirement of the population and there are no better pesticide alternatives that we know of at this time that are less harmful.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Pingback: Environmental impacts of farming | Thoughtscapism

Pingback: ‘Treatment-free’ beekeepers give Varroa mite free rein | Thoughtscapism

The Environmental Risks of neonicotinoid pesticides: a

review of the evidence post-2013

Click to access 098897.full.pdf

The risks to birds, aquatic organisms, and other taxa has not been collated in one place, so this report attempts to do just that. Neonics are not the benign “crop protection products” the marketing language has repeatedly used. This report is a grounded examination of the unintended consequences of our reliance on chemicals and their usually prophylactic usage.

Susan, beekeeper

“Relative to the risk assessments produced in 2013 for clothianidin, imidacloprid and thiamethoxam which focussed on their effects on bees, new research strengthens arguments for the imposition of a moratorium, in particular because it has become evident that they pose significant risks to many non-target organisms, not just bees.”

LikeLike

I think you didn’t (yet) include this study (2017): Country-specific effects of neonicotinoid pesticides on honey bees and wild bees) http://science.sciencemag.org/content/356/6345/1393

From the abstract: “[…] For honey bees, we found both negative (Hungary and United Kingdom) and positive (Germany) effects during crop flowering. In Hungary, negative effects on honey bees (associated with clothianidin) persisted over winter and resulted in smaller colonies in the following spring (24% declines). In wild bees (Bombus terrestris and Osmia bicornis), reproduction was negatively correlated with neonicotinoid residues. These findings point to neonicotinoids causing a reduced capacity of bee species to establish new populations in the year following exposure.”

LikeLike

Haha, no didn’t include them yet, but I have been reading and discussing these papers which came out on Thursday (so soon three days ago). I can include the posts I’ve made on FB on the topic here:

Two new bee papers out! One of them was aimed to be a comprehensive test of neonicotinoids and… once more, its results are inconsistent. Three countries, a whooping 88 variables measured (different health measures, wild and honey bees, etc), but only 8 came out significant. Three of them even showed a *beneficial* correlation between neonicotinoid treatments and bee health. Much of the results were botched altogether because…. pests and diseases, particularly the Varroa mite, killed off many of the UK hives. But the study did not choose to track those variables.

This Arstechnica piece by a long time biology researcher gives a good short introduction to these science news (which are reflected in all kinds of headlines in the media already).

“a team of independent researchers purportedly tied neonicotinoids to bee colony health. But a quick look at the underlying data shows that the situation is far more complex. And a second paper, with more robust results, supports the idea that these insecticides are merely one of a number of factors contributing to bees’ problems”

https://arstechnica.com/science/2017/06/study-paints-a-confused-picture-of-how-insecticides-are-affecting-bees/

This also seems like an noteworthy factor, pointed out by an entomologist:

“But all three treatments (the control and the two different neonicotinoid treatments), had different fungicide treatments applied with them, violating the basic scientific rule to control all variables apart from the one you are interested in, or at least account for these other variables. This study, unfortunately, has confounded neonicotinoid treatment with fungicide treatment, so it is not really possible to draw many conclusions on neonicotinoids alone. So my personal opinion is that the effect on honey bees in this study is ambiguous at best.”

https://sciblogs.co.nz/guestwork/2017/06/30/more-evidence-on-the-effects-of-neonicotinoids-on-honey-bees-maybe/

Another good article on the new bee research, with a very responsible headline. Pesticides are likely to have some negative effects on bees, even though it is hard to pinpoint the realistic degree of the effect (and the effect in the large European study shows mostly non-significant effects, a handful of harmful, and even three correlations in a positive direction).

Nevertheless, it is clear that we can’t address the bee problem if we ignore the larger problems of pest, disease, and habitat loss.

“The differences between bees in treated or untreated fields were largely insignificant, and many of the bees in both groups died before they could be counted. ”

…

“the small number of significant effects “makes it difficult to draw any reliable conclusions,” said Norman Carreck, science director of the International Bee Research Association, who was not part of either study.”

…

“Christopher Cutler, who studies insect toxicology at Nova Scotia’s Dalhousie University, echoed Carreck’s concerns, pointing out that “when many different analyses are conducted” (42 in this case), “a small number of statistically significant effects are bound to emerge by chance.”

…

“An approach popular with activists would be to ban neonicotinoids altogether, but many experts worry this would cause farmers to turn to older and potentially more harmful methods of pest control. “Things are better for honey bees since neonics replaced more harmful insecticides,” said beekeeper and science blogger Randy Oliver.”

https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/speaking-of-science/wp/2017/06/29/controversial-pesticides-may-threaten-queen-bees-alternatives-could-be-worse/

The inclusion of the total data of the European paper in this piece is quite illuminating. 258 enpoints measured, 238 of them find no difference with or without neonicotinoids. 7 find a positive, 9 a negative effect (4 no data).

http://www.slate.com/articles/health_and_science/science/2017/06/the_data_do_not_support_the_idea_that_neonics_hurt_bees.html

The short of it is, there are still very little and inconsistent evidence for harm from neonicotinoids for bees in field conditions. Some harm in certain conditions does seem very plausible. Similar or more harm from neonicotinoid alternatives, as well as environmental drawbacks, seem likely however, if neonicotinoid use were to be banned altogether, and pests, disease, and habitat loss appear to be much larger issues.

Hope this was helpful. Thanks for posting!

Iida/Thoughtscapism

LikeLike

Thanks for this answer!

LikeLike

Ended up writing a piece on this as well: “What seems problematic in the logic of the authors, is that if the three observed beneficial effects can be considered the result of factors other than neonicotinoids, then the same could be said about the five cases where they detected harmful effects. If you consider that significant effects in either direction represent a very minor portion of the results, it seems like an awful lot of weight is being put on these five findings.”

LikeLike

Pingback: New Study Finds Neonicotinoids May Have Harmful, Beneficial, or No Effects on Bees | Thoughtscapism

Pingback: New study on neocotinoids and bee health finds little effect

Pingback: ‘Treatment-free’ Beekeepers Give Varroa Mite Free Rein by Thoughtscapism | Beekeeping365

Pingback: No, Glyphosate Is Not a Threat to Bees | Thoughtscapism