Infestations rarer among professional beekeepers

Hobby beekeeping is very common. A European Bee Health Report found that in many countries, the majority of beekeepers pursue the activity as a hobby. They give Germany as an example: 80% of beekeepers keep just 1–20 colonies, 18% keep 21–50 colonies and only about 2% keep more than 50 colonies. They note that improving expertise and education are likely good ways to improve honey bee health.

I have delved into the complex factors of bee health earlier in the piece If You Care About Bees, Look Past Neonicotinoids

They may be on to something. In fact, in the past months two scientific publications – a large European surveillance study, and an essay in Journal of Economic Entomology – turn the spotlight on bee management, holding handling factors, like the lack of appropriate treatment, largely accountable for the spread of bee mites and diseases.

Bee epidemics have become a growing problem for both wild and cultivated bees thanks to the spread of the cultivated European honey bee. The Varroa Destructor mite is at the core of the problem, because it also passes on bee diseases (I have discussed this more at length in my earlier bee health piece).

The recent Pan-European epidemiological study reveals that honey bee colony survival depends on beekeeper education and disease control. It shows that it is first and foremost hobby beekeepers, who have trouble with epidemics:

[…] honey bees kept by professional beekeepers never showed signs of disease, unlike apiaries from hobbyist beekeepers that had symptoms of bacterial infection and heavy Varroa infestation.

The Essay in Journal of Ec. Entomology, Role of Human Action in the Spread of Honey Bee (Hymenoptera: Apidae) Pathogens, similarly asks beekeepers to look in the mirror, pointing out both inappropriate and un-approved use of treatments, which has hastened development of resistance, as well as the failure to treat Varroa infestations, especially among hobby beekeepers. As reported in the ScienceDaily:

The opportunities for arresting honey bee declines rest as strongly with individual beekeepers as they do with the dynamics of disease.

These ‘poor management practices’ pointed out above, however, may have less to do with errors or lack of education, and more to do with the personal convictions of the beekeeper, as one hobbyist beekeeper recently led me to understand. I decided to investigate, and I didn’t have to look long.

It turns out that for thousands of beekeepers, ‘management’ is a dirty word.

There are blogs, groups, a podcast, even a conference dedicated to going ‘treatment-free’, or ‘TF’ as they  call themselves. Some go as far as to say that any interference on behalf of the well-being of the hive is wrong. They think the Varroa mite should simply be allowed to run its course.

call themselves. Some go as far as to say that any interference on behalf of the well-being of the hive is wrong. They think the Varroa mite should simply be allowed to run its course.

I had stumbled upon the anti-vaccine equivalent of the beekeeping crowd. Let me walk you through what I found.

Hobby beekeepers flock to ‘treatment-free’ trend

I had to follow up to see if this ‘treatment-free’ philosophy really was a thing. True enough, there is at least a Facebook page called Treatment-free beekeeping, and it has more than 16,000 members. They define their group ethos like this:

[…] treatment-free beekeeping and the promotion thereof. We do not talk about treatments except to mention, in passing, the damage they cause.

The rhetoric is chillingly alike to that of the anti-vaccine proponents’: only expressing ideas about the purported dangers of the treatments is okay. This is concerning, considering that there are always risks to every choice we make, as with whether to treat or not to treat. It is only careful evaluation of those risks in context that can tell us which is the best choice to make.

In this case, thinking of risks in context goes out the window, however, for ‘treatment-free’ philosophy encourages allowing Varroa mites to kill bees. The infestation is seen as something ‘the hives must go through’, whereas any potential harm from treatments is to be avoided, period.

I continued looking to find out how widespread this line of thinking might be. I found the Treatment-free beekeeping podcast, which has over 100,000 downloads. I even stumbled on a Treatment-free beekeeping conference, held in the US for the 10th time in March 2017. Among their list of speakers, the official sounding title of ‘the director of the International Natural Beekeeping Federation’ caught my eye, represented by its director, Laura Ferguson. I quickly discovered that the federation seems only to exist on Facebook, however, but her other title ‘director of a Center for Sacred Beekeeping‘ yielded a web page. Reading from it, her aim is to bring a more ‘holistic’ view to beekeeping, so that it will be more ‘in tune with nature’. On her page she also refers to a ‘Bee healing guild’, a ‘non-profit BE-ing’, where Lady Spirit Moon teaches courses on ancient healing with bee venom. I feel we have come rather far from the earthly realm, where bees live, at this point.

It appears that this ‘treatment-free’ movement may be opposed to most scientific recommendations on bee management, and are more interested in what appeals to them as ‘natural’. Part of the attraction may also be a sort of ‘laissez-faire’ attitude, having an approach to beekeeping that requires less work – one ‘TF’ beekeeper and blogger I found, at Parker Farms, says his aim as a promoter and practitioner of ‘TF’ is to ‘eliminate dependence on the back-breaking and time and energy intensive manipulations’ in beekeeping.

This bee has a Varroa mite attached and it has suffered the results from the Deformed Wing Virus which Varroa spreads.

In fact, he argues that ‘treatment’ should be avoided on all levels, whether it be pest repelling substances or other ways of beekeepers interfering in bee survival. Anything ‘introduced by the beekeeper into the hive with the intent of killing, repelling, or inhibiting a pest or disease afflicting the bees, or in any way “helping” the bees to survive’ – even artificial feeding of a weak hive is a no-go. Being TF, he says, means also swearing off ‘manipulations or equipment that are done/introduced with the intent to “help” the bees survive’. He writes:

So, what is ‘treatment-free?’ Treatment-free is the way bees live in the wild. It’s the way the species ultimately survives. And it’s why I don’t treat my bees and you shouldn’t either.

[…] It’s a harsh reality, but nature consists of one harsh reality after another. It’s why gazelles are fast and cheetahs are faster.

This gives me pause. By this logic it is very much okay if a number of bee species should die out thanks to the Varroa mite and disease – those bees just weren’t strong enough as species. Too bad?

Many conservationists seem to disagree with the idea, and consider that if wide-spread cultivation of honey bees has caused a disease-epidemic, we should take steps to control it, and stop it from spreading to susceptible wild bee species. Diseases do spread when they have the opportunity to do so – that is perfectly natural. But ‘natural’ does not equal good, and if we are focused on the naturalness of things, current spread of bee disease does not fit the bill to begin with: a study from 2016 supports the view that the spread of bee diseases is man-made – commercial honey bee trade emanating from Europe is largely responsible for the spread of Varroa and Deformed Wing Virus.

Taking these factors into account, a ‘treatment-free’, ‘natural’ beekeeping philosophy may often result in exacerbating a human-made spread of epidemics, allowing human-introduced animals to suffer, and then in defending that experiment as the ‘natural way’. (European honey bees are, quite literally, a non-native, introduced species in the US).

It is not to say that we should not look for strains of bees with better resistance to mites and disease – but as an experienced beekeeper and blogger over at Scientific beekeeping points out, there are breeding programs and better choices of queens on one hand, and then there’s just bad management that creates problems for your bees on the other:

allowing untreated colonies of commercial stock to die from varroa year after year benefits no one, and hurts both your neighboring beekeepers, as well as the evolutionary process. […] So long as beekeepers continually replace varroa-killed colonies with fresh colonies of similar bloodlines, we artificially maintain the situation of an initial invasion, favoring the most virulent strains of the parasites. This makes it nearly impossible for any colonies with genes for resistance to survive, due to their being overwhelmed with mites from their collapsing neighbors.

From organic to ‘treatment-free’, to realizing beekeeping itself is not natural

The Parker Farms blogger laments that the organic label has gone downhill, having approved the use of too many ‘chemicals’ for his liking – he also scorns organic-approved treatments like essential oils. The Organic beekeepers Yahoo group (with over 6,000 members) supports this view as well, swearing off artificial feeding as well as any treatment of bees, whether natural of synthetic in origin.

The Parker Farms blogger is of the view that only professional beekeepers need treatments, because their bees are more stressed due to transport (migratory). What ‘needs’ means exactly, is unclear, as the presence of Varroa mite among TF beekeepers is definitely common – according to their philosophy it just doesn’t warrant treatment. Another TF blogger from Vermont talks about how a TF beekeeper will as a rule ‘have to watch’ one’s bee colonies die off at least twice due to Varroa infestations. He underscores that the Varroa Destructor mite should be treated as a ‘friend, ally and mentor’. In fact, he thinks beekeepers have a disproportionate role in ‘choosing which path to follow’, and hopes that by letting Varroa reign ‘as a friend’, it will result in a ‘world based on creativity and biological energy’.

‘Natural’ enough bee home?

This trend in thinking that humans should not interfere at all seems to have escalated to the point where even the TF beekeepers Facebook-group has had to take a tighter tone with their members, forbidding further topics of discussion – such as how bees should not be put in man-made hives to begin with.

Can’t fault those who made such suggestions, for it makes sense, if you follow the logic. Interfering is interfering… Beekeeping and honey-production itself can’t truly be considered ‘natural’. From the group’s pinned post:

We have had a number of threads with people proposing, essentially, that ‘all Beekeeping is a treatment’ – all bees should be in hollow trees and we should simply pack up out kit and go home. This line of reasoning is extended to say that if we are ‘treating’ by putting them into hives, then we aren’t Treatment Free so should allow other ‘treatments’ as well.

This line of argument is seductive to some, but flawed. It is seductive because it opens the door to allowing some forms of treatments, which makes beekeepers feel they can ‘help’ their bees. However this whole principal of ‘helping’ bees with mites works against the objectives of this group.

The TF beekeepers outlooks seem nothing if not optimistic. They seem to think that bees will be just fine without any help. The objective of TF proponents appears to be to let the evolutionary game play out, and see whether bees survive or not.

What happens to bees without treatment?

Does the ‘survival of the fittest’ experiment allow hobby beekeepers to sail clear of bee epidemics? Well, so far, the recent European study (discussed in the beginning) reported Varroa infestations exclusively among the hobby beekeepers (professional beekeepers seem less inclined to follow the TF philosophy). I can’t find exact data about the prevalence of TF beekeepers in Europe, so I can’t tell if this effect may be in part due to a refusal to treat the bees, but a 2016 analysis of the same Epilobee data (used in the European study) may hint at such a trend. They found Varroa mite infestation to be correlated more with hobby beekeepers with lack of cooperation with veterinary treatments. They found smallest losses among professional, migrating apiaries:

the highest winter mortality rate (14.04%) was affected to a cluster including hobbyist beekeepers over 65 years of age with small size apiaries, with a production including queens and a small experience in beekeeping. The lowest winter mortality rate (8.11%) was affected to a cluster with professional beekeepers between 30 and 45 years of age, with large migrating apiaries. The management promoted the increase of the livestock.

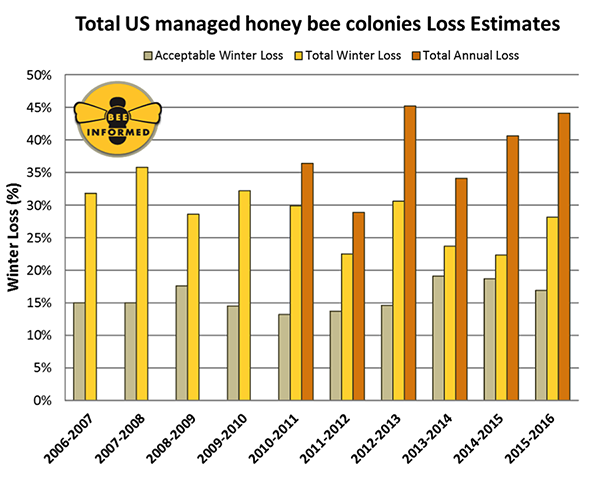

Looking at the situation in the US, a five-year -study clearly reports that the majority of hobby beekeepers do not treat for Varroa infestations. The US also continues to have the highest overall colony losses, with 44% during 2015–2016 according to Beeinformed 2016. In Europe, losses are much lower (see detailed sources of both US and Europe in the next chapter).

Bee with a Varroa mite on his back. Photo by USDA.

The US five-year -study paints quite a gloomy picture of the consequences:

National winter loss surveys indicate that 60 % of hobby beekeepers do not treat for Varroa (Steinhauer et al. 2014). Without beekeeper Varroa management interventions, these colonies almost inevitably crash (Francis et al. 2013), releasing abundant mites that invade healthy colonies by switching from nurse bees to foragers (Cervo et al. 2014) and swapping hosts via communal foraging or robbing (Frey et al. 2011).

The Food and Agricultural Organisation of the United Nations has a guide to honey bee diseases, where they outline the sad consequences of an untreated Varroa-mite infestation in a very similar fashion:

Without treatment the colonies normally die after two to three years […] In this way mites may cause colonies to die, as in some kind of domino effect, over wide areas.

The FAO guide notes that ‘The control of V. destructor is one of the most difficult tasks facing apiculturists and beekeepers throughout the world.’ Seems they haven’t considered the TF-beekeepers’s philosophy – it’s not difficult at all if you don’t have to lift a finger against it.

Perhaps it comes as no surprise, then, that the five-year study finds Varroa mites and viruses to be spread even more widely in the US than previously assumed. As reported by Science Daily:

Key findings show that the varroa mite, a major honey bee pest, is far more abundant than previous estimates indicated and is closely linked to several damaging viruses. Also, the results show that the previously rare Chronic Bee Paralysis Virus has skyrocketed in prevalence since it was first detected by the survey in 2010.

So, how are honey bees faring?

While discussion about definition of Colony Collapse Disorder (CCD), and which kind of losses constitute CCD, can be complex, the fact remains that honey bee losses in the US have remained higher than usual – according to the USDA, before Varroa epidemics, over-winter losses were 10-15% each year. Now, between 2007-2016, winter losses have been at 22-36%. Managed bee populations are able to compensate for these losses, split hives more often, buy more queens and bees when necessary, so honey production is not in danger.

However, the summer losses are high as well, as documented by the Bee-Informed survey (funded by the USDA), highlighting that there are significant problems facing bees still. Their piece points first and foremost to the problem with Varroa mites, noting, surprise surprise, the problem of hobby beekeepers, who may not know how – or as noted above – choose not to correctly stop their spread.

European honeybee situation looks a little better. Most of the European surveillance programs track winter losses, but at least one large data collection, Epilobee, in 2013 looked also at summer figures, and found them to be lower than winter mortality rates, ranging from 0.3% to 13.6%.

Europe-wide average statistics for winter losses fluctuate between 9-18 % (2010-2016 – see graph below), as tracked via the COLOSS project (see a recently published paper on its data, the project itself, or the Bee Health in Europe report presenting that data). In the lack of weighted summary statistics for the earlier years, various country averages in Europe ranged between 7-22% in 2008-2009, and 7-30 % in 2009-2010, according to Opera Research Center report on Bee Health in Europe.

Historical variance for some European countries can be found quite far back, like in Sweden, where average winter loss rates have been recorded to range between 6-27% in the last century (1920-2012). In the last decades, Finland recorded 10-34% average losses (1998-2008) and France 17-29% (2005-2008).

Historical variance for some European countries can be found quite far back, like in Sweden, where average winter loss rates have been recorded to range between 6-27% in the last century (1920-2012). In the last decades, Finland recorded 10-34% average losses (1998-2008) and France 17-29% (2005-2008).

Best advice to beekeepers?

It is clear that honey bees do suffer fluctuating losses, and the reasons are many – as I have discussed before. At present, pests and disease are among the largest concerns for bee health. The honey bee industry is coping with the situation, but the pest problems are real and in need of solutions – and letting the bees battle it out against their adversaries without outside help is not the recommended course of action from bee researchers or invertebrate conservationists. The scientific advice to beekeepers is summarized well by the Honey Bee Health guide to Varroa management:

remain vigilant to detect high Varroa mite levels and be prepared to take timely action in order to reduce mite loads. Effective mite control will reduce colony losses and avoid potential spread of infectious disease among colonies.

Luckily there are many beekeepers out there who listen to this advice, and help promote an evidence-based outlook to best bee management – see for instance the resourceful blog Scientific beekeeping by Randy Oliver, who tries to bridge the gap and reach also the ‘treatment-free’ hobby beekeepers, providing knowledge about when and how being treatment-free is realistic. He offers some great advice for beginner beekeepers, and makes the following plea:

I beg all beekeepers (professional and hobbyist) to become part of the solution to The Varroa Problem. Either get involved in a realistic breeding program, or support those who are by purchasing stock from them. And most importantly, monitor your hives for varroa, and treat them (if necessary) before they collapse, so that you don’t become a nuisance to the beekeeping community.

The larger version of the infographic I made to summarize the complex landscape of bee health

What is especially worrisome is the increasing concern that wild bees are taking a hit too, thanks to disease epidemics spread by commercial honey bee populations, recently reported by InsideScience, in How the Bees You Know are Killing the Bees You Don’t:

…the leading suspect in their disappearance is disease spread by other bees — commercial bumblebees raised by humans to pollinate crops.

It is important to remember that one big factor in the bee situation is habitat loss – if you would like to help the bees, plant native flowers to help create more natural habitat for all bees. Please think twice, however, before starting a honey-bee hive, especially if you do not think you want to put in the work needed to keep the hives disease-free. Please don’t join a movement bent on increasing the man-made spread of bee disease.

Update: While I am happy that my piece has attracted the attention of many beekeepers, unfortunately I don’t have time to keep up with all the commenters and address all of their questions and claims, many which seem to miss some of the points presented in my piece.

For those interested in bee breeding, please get in touch with scientists and strive to take part in realistic breeding programs. Please don’t simply assume that the scientists researching bee issues, as well as the USDA, FAO, etc, must simply be ignorant of the issue and you know better. It just may be more complicated than that.

Things in life and nature are seldom black-and-white (or boiling down to never treat / only treat). In the words of my local evolutionary biologist with a PhD in bumblebee disease (who also recommends formic and oxalic acid treatments): “I get the idea/hope that without treatment the bees will evolve resistance, but it doesn’t quite work like that and it definitely doesn’t work quickly.”

Echoing that sentiment, please do not dismiss the words of the leading American bee scientists, vanEngelsdorp, as being the result of simply not knowing better, from Scientists Recommend Treating Bees for Varroa Mites:

…research shows mortality is much lower among beekeepers who carefully treat their hives to control a lethal parasite called the Varroa mite.

“If there is one thing beekeepers can do to help with this problem, it is to treat their bees for Varroa mites,” said vanEngelsdorp. “If all beekeepers were to aggressively control mites, we would have many fewer losses.” […]

“Every beekeeper needs to have an aggressive Varroa management plan in place,” vanEngelsdorp said. “Unfortunately, many small-scale beekeepers are not treating their bees, and are losing many colonies. And those colonies are potential sources of infection for other hives.”

More of my articles on the the topic of The Environment here. If you would like to have a discussion in the comments below, please take note of my Commenting policy. In a nutshell:

- Be respectful.

- Back up your claims with evidence.

Very nice summary of a complex issue. Treatment-free is another manifestation of the “balance of nature” thinking that has infiltrated our thinking. Here in Washington state, we try to discourage homeowners from planting apple and pear trees because they often do not treat for pests, either by choice or by neglect. This not only ruins their fruit, but provides pest refuges that undermine the commercial control efforts.

LikeLike

Andrew, if do a quick Google search on “refuge zone for pest management” you may find some interesting information. To make it easier, I’ll give you a link directly to Monsanto (http://www.monsanto.com/products/pages/refuge.aspx) and take a quote from that page, “The purpose of the refuge area is to prevent pests from developing resistance to the technology.” Simply put, we cannot kill every bug to the extent that those bugs will not evolve resistance. So unless we maintain some vector of susceptibility to the poison in that population, the poison becomes ineffective. In truth, those homeowners who plant and don’t treat their apple and pear trees are doing the commercial guys a favor by saving them for planting and maintaining a refuge of their own… Cheers!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Charles, you are right, but I was using the word refuge differently, for a different form of control – pheremones for coddling moth. To be successful, this non-toxic control must be widespread, as far as I understand it, and homeowners who do not control the moth in some way mess this up.

LikeLike

Hey there, this is Solomon Parker, purveyor of a bunch of the TFB stuff you quoted above. If you are interested in a balanced view of what you’re talking about, I’d be happy to give you an interview.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Hello Mr Parker

Thank you very much for your offer, and for the friendly manner in which you made it – despite my piece being critical of you as a representative of the TF movement. Polite discourse is not very common on the internet, so I would like to express my appreciation for that right off the bat.

Would you like to elaborate here on the aspects you found unbalanced in my presentation above, so that the blog readers may see it? A trip over the Easter Holidays is likely to keep me busy for a while now, but your comments would be directly available for everyone here in the context of the piece.

Thanks once more for the offer. I am truly interested in your point of view, and I ask only that strong claims be supported by evidence, and considered in the context of the best available evidence overall.

In the meantime, Happy Easter!

Best regards,

Iida/Thoughtscapism

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi there, sorry I just saw this now. I wrote this off as a biased article long ago and had no intention of coming back to it. But users of my Facebook group still seem to want to discuss it, so I checked back.

I’m not interested in debates, much less in the internet comments of a hostile article. But I’m still happy to provide myself for an interview, or if you’d be interested, I’d love to have you as a guest for a conversation on my podcast, the Treatment-Free Beekeeping Podcast. If you truly want to discuss the concept with a real long term treatment-free beekeeper, I’m always interested. And you’d have direct access to the audience this article is aimed at debunking. I promise unlimited time, unedited recording. I love talking about this stuff, because it really is about the science of natural selection, the driver of evolution on our planet. What we’re seeking is bees that don’t need our inputs to survive. When humans are extinct, bees will probably still be here, and if they can’t survive without us now, how will they survive after the end of civilization? Though, it’s not really a problem, because they already are.

Anyway, I look forward to hearing from you. I have a pretty open schedule. Please contact me on Facebook or through the contact page on my website.

LikeLike

Believing that regular treatment or the use of prophylactic chemicals is not the sustainable solution to the problem is in no way comparable to those who shun vaccinations. Vaccinations are a known and proven preventative measure, which creates natural resistance. There is no form of treatment for varroa that is anything more than temporarily effective and usually with only 80% or so reductions in mite numbers.

While I agree that hobbyist beekeepers who simply replace lost stocks with swarms, or worse, package bees with known susceptibility, are doing nothing to help with the development of resistance, those who carefully select their stocks for observable behaviours, like uncapping cells and removing parasitised larva, are promoting the development of resistance.

Rather than promoting a ‘them’ and ‘us’ philosophy, national beekeeping organisations should be doing what is already done in France, distributing resistant queens around the country, and undertaking breeding programmes of ‘super hygenic’ bees.

The eventual solution can only be for resistant bees to predominate and both regular treatment by the professionals and the current behaviours of most hobbyists simply present obstacles to this.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hello Historyman,

Thanks for your input. I very much agree with you that carefully selecting for behaviours that help fend off the Varroa mite, and working toward a situation of not needing to use treatments, are good ideas. I am happy to hear about national breeding program for more resistant queens in France. Would you happen to have a link where I could read more about that?

There are naturally many dissimilarities between the TF movement and the anti-vaccine one, and vaccines and varroa treatments are very different in essence. Vaccines are very effective and safe and they preventative, whereas management and treatment for Varroa is largely about monitoring and reacting appropriately. The treatments are varied in effect and safety, and suit different situations. Improper use may create resistance in Varroa, and their use is altogether more complicated than simply getting a vaccine shot. Withholding treatment also brings no human suffering.

But I argue that there are few striking similarities as well. I outline the grounds for my comparison in the piece by specifying which aspects were similar. I can elaborate on that here.

There is a similar aspect of ignoring official health recommendations. Beekeepers who don’t protect their charges via proper IPM practices, to people who don’t protect their charges via proper vaccination practices. As a result of this behaviour, the situation is worse than it should be.

The analogy extends to the thinking I found expressed by some beekeepers, that the Varroa is a ‘good thing’. I don’t think all anti-vaccine parents share the view that diseases are good, but there are many who do. Similarly, there is probably plenty of heterogeneity of views among TF beekeepers, and they all have their personal outlooks on it.

There is the similar idea that simply allowing the disease to run its course strengthens the gene pool, without concern to the quite complex concepts of evolution and disease epidemics in practice.

I also compare the mindset of swearing off all medical means, and the culture of only allowing discussions about the harm in the treatments – being less afraid of disease and more afraid of the thought of applying any ‘chemicals’.

Add to that the pseudoscientific healing beliefs which I stumbled on to in this context (courtesy of Sacred Beekeeping and Lady Spirit Moon), which is similar to the trends often seen in the anti-vaccine circles. I’m sure many beekeepers do not hold these views, as, say, many anti-vaccine parents may not use water pills as medicine.

Anti-vaccine crowd causing much more suffering than bees is clear from a human perspective, as we talk about humans in that case, not bees. But this extreme mindset of avoiding all treatments and even any other intervention is still problematic. I do think we need to point it out and try to make people see why they should take a more evidence-based look at beekeeping, because they can have a significant influence on disease epidemics – alike to vaccination choices.

As mentioned in the piece, in the quote of Randy Oliver from Scientific beekeeping, taking part in a realistic breeding program is a good initiative. He also makes a great effort, I think, in trying to bridge the gap and reach out to TF-beekeepers, working together instead of trying to create sides. I understand that my honest astonishment over finding out about (more extreme aspects of?) the movement can come off as antagonising, and I am sorry if it has offended TF beekeepers. I hope I have managed to politely explain the basis for my concern.

I imagine most beekeepers would want to go without treatment, and have happy, healthy bees, and the differences are only about the best ways of getting there. Based on the evidence, it appears that some ‘ways of trying to get there’ applied by a well-meaning TF-attitude may be counterproductive, and with this piece I hope to draw attention to that.

Thanks for reading and for sharing your thoughts.

Best regards,

Iida/Thoughtscapism

LikeLike

Lida, While it may be a reasonable generalization to say antivaxers would probably be of the mindset that bees should be kept treatment free, to say all treatment free beekeepers have the same thought processes as antivaxers is erroneous and does not add to the discussion of the topic, to treat or not to treat. Labeling treatment free beekeepers in such a way is an “ad hominem” (logical fallacy in which an argument is rebutted by attacking the character, motive, or other attribute of the person making the argument) and in no way advances your argument logically. Since you seem to strive to stay above the fray in your discourse, I would suggest you include that consideration in your thought processes.

I’d like to inject the concept that all parasites must naturally come into equilibrium with their host. Because if they didn’t they would themselves die without any hosts. If you except that premise, varroa left to their own devices would either a) wipe out all honey bees and then cease to exist themselves, or b) come to an equilibrium such that they can successfully parasitize their host without killing them. As a treatment free beekeeper, I subscribe to the later. As a comparison, if we look historically, we will see the same pattern as tracheal mites at one point in time were a major parasitical impact on bees and nearly wiped out bees in England. Thanks to Brother Adam and his work developing the Buckfast bee, he was able to breed a bee that was resistant, all without any treatments. Tracheal mites still exist today, but they have come into balance with their host. So we have concrete historical proof that this type of thinking and solution is reasonable, valid and does work. Cheers!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hello Charles,

Thanks for sharing your thoughts.

I would like to point out that I didn’t use the anti-vaccine analogue as a ‘bad name’, which would be an ad-hominem, but to point out similarities in behaviours, which I then outlined. I have earlier dedicated a lot of time to address many of the problematic beliefs and behaviours of people who are anti-vaccine, and I have never in those contexts used the term as an ad-hominem either.

If you wish to criticize my viewpoints, then defend the problematic behaviours I described just above. To name a few anew:

-ignoring best available recommendations from agricultural institutions and bee researchers, thus allowing diseases to spread,

-acting on the basis of an over-simplified idea of evolution,

-committing the natural fallacy on how problems should be approached. ‘Chemicals’ does not equal bad, ‘natural’ does not equal good. Questions of better or worse approaches are much more complex than that.

I am happy that one parasite problem was earlier in history overcome by a bee breeder, and I welcome other such serious efforts of bee breeding. That, however, was the meticulous works of decades of deliberate bee breeding (70 years apparently) – exactly what I in my piece advocate for, as well, and quote Scientific beekeeping blog on – not the work of letting all cultivated bees among hobbyists the continent over continuously get overwhelmed by their parasite.

As an evolutionary biologist and friend of mine expressed it: if bees have small genetic variance in their ability to resist the varroa mite, then increasing pest pressure will not help. If there’s not enough variation, or selection is too strong (pest pressure), then you get extinction and not adaptation. What you need is a broadening of the genetic material to work with. In any case, you need a realistic breeding program.

Making bees with little resistance vulnerable to the pest and allowing them to spread the epidemics does not solve the problem. It upholds an ‘unnatural’ pest presence, which increases the pests’ chances of overwhelming the host, undermining any natural state of balance that may have existed before bees had so much contact with each other thanks to human beekeepers.

Being a bee breeder is one thing. Being a person with a few bee hives who refuses to treat them and allows them to spread parasites to others, is quite different. I welcome the former, and wish to draw the latter group’s attention to the complexities of bee health, and hope they will consider the most solid, evidence-based advice I can find from bee experts on the best ways forward.

Thanks for your interest in my piece, and Happy Easter,

Iida (that’s ‘iida’, btw :)/ Thoughtscapism

More on the Buckfast bee for those interested: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Buckfast_bee

LikeLike

Is there a photo credit on the picture of the live bee with a mite on its back? I would like to use that photo in a presentation without violating copyright. Thanks.

LikeLike

I found it labeled as public domain here: https://pixabay.com/en/bee-honeybee-honeycomb-close-up-85576/

Interestingly, now a search with different keyword returned the same photo as a USDA flicker photo, where they ask for attribution: https://www.flickr.com/photos/usdagov/14175583191

So I’ll add that. Thanks for asking, so I found out as well.

LikeLike

It is nice to see, argument for and against a subject so reasonably put, and with such well moderated responses. I lived in New Zealand for a while and regularly kept bees that would swarm on my property, but I did not take honey from them – they were kept out of interest and also to pollinate native flowering plants that I was re-introducing – because initially I had few native insects and birds visiting to do the job. I did not mention to anybody that we had a wild bee’s nest in the vicinity (even though I knew where it was), because I was told the Department of Conservation would destroy it because they feared the spread of disease. The colony was doing well and I think there is more to be gained by allowing wild colonies that are not heavily affected by parasites to continue to exist. Many of the problems that occur in the natural world are caused by farming; I am not suggesting that this is a reason to stop farming, but it should at least be recognised – keeping animals in artificially high concentrations is certain to promore disease. Any place there are flowering plants that rely on insect pollinators will have a full compliment of pollinators already present with none of the flowers simply waiting for honey bees to show up and honye bees will be competing with them. I don’t want to get involved in the arguments for and against pest control, just to say that bee keeping is essentially farming and has its own compliment of problems which impinge on the natural world. We should simply recognise this and fully appreciate the consequences. My bees never had problems with mites or other micro-organisms. Mostly it was introduced European wasps raiding and overwhelming the colony that caused problems. In this case, it was one introduced species hammering another.

In the original article I think it is a mistake to make a comparison with anti-vacinators; I understand why this has been done, but the basic premise is different.

LikeLike

Hello Stephen,

Thanks for commenting. I am very happy that all commenters here so far have demonstrated a very civil and eloquent type of discourse, so that I have not had to moderate at all.

You are spot on about this being a farming-problem in essence. I find your thoughts on this very similar to mine. Bees are livestock, and it’s the way we keep them and trade them that has created the situation we have today. Fitting together the agricultural needs and wants of such a large human population and those of those of the natural world is not an easy or a simple problem. I hope that following the best possible evidence as honestly as possible, we can improve on our ways of co-existence.

I respect your opinion about the use of the comparison. If I should reflect more on what in the premises of the two movements is most different, I would perhaps say that those who are anti-vaccine often act out of a close and personal fear, whereas the TF movement might be more about a general romanticism and yearning for a simpler time of co-existence with other animals and feeling one with nature.

Bearing the cognitive burden of being a part of an advanced society of very numerous populace with complex relationship to rest of the natural world, with mixed feelings of ownership, responsibility, and guilt can sure be a much more exhausting way of looking at things.

Thanks for stopping by,

Iida/Thoughstcapism

LikeLike

Hey Iida, sorry for misspelling your name on a previous reply. I only caught the mistake after I had hit submit and at that point I was unable to edit my post… mea culpa.

Just one more thought in regards to your viewpoint or characterization of treatment free beekeepers in which you still wish to basically dismiss them. Aligning a group of people with another or generalizing your classification of them, again and firstly, does nothing to advance your arguments in regard to the merits of or the necessity for treating bees. It would be best to completely leave those thoughts out of the discussion. As you rightly identified. The world is very full of so many people, that any generalization of them is very likely to be an over simplification which is exactly analogous to your point in terms of the complexity of nature. You advance the point that treatment free beekeepers are over simplifying the problem so they can justify a position. I’m saying you are doing the same by judging and otherwise classifying a group of people who happen to fall into a broad spectrum of people who loosely fall into common alignment on a particular point.

Hopefully you can appreciate the nuanced point I am making… I will get back to you with more counter points to your reply to me above as soon as I can find enough time to give a reasonably cogent and accurate response. This is precisely why I usually do not bother responding to posts like these because it becomes a job in of itself! 😀 Cheers!

LikeLike

I am a TF beekeeper in Los Angeles with 30 hives of feral sourced survivor stock honey bees that are never treated, are foundationless, and do not get any artificial feeds. I teach beekeeping via referrals from the public and municipalities, mentoring students in the craft of re-homing feral colonies from structures, tree limbs and other typical urban sites. I find this piece to fails to articulate the essence of the philosophy for not treating Apis mellifera for Varroa destructor and its vectored diseases. All creatures deal with pests and disease, and the Darwinian concepts of selective adaption to pest and disease pressure are at THE HEART of the TF model. It has become increasingly evident to me that the failure of newbees to learn the genetic requirements and sourcing for the bees they keep ( they “fall in love” with the TF idea but do not find out what the genetic underpinnings of the model require) leads to a massive level of failure, with the seasonal re-purchase of package bees raised on treatments a recipe for loss. In your quote of the TF beekeeping group guidelines, the copy does not include this important part “The basic philosophy behind a TF approach is that treating bees for diseases prevents the bees from developing the various genetic adaptations they need to be able to cope on their own. ” The attention must be on GENETICS of the bees being used. Package bees from breeders are notoriously susceptible to V.d, the queens are NOT related to the workers they are combined with, and the genetics of these bees have been heavily selected to reflect human desired traits that do not serve the bees. Since the piece mentioned Randy Oliver, I urge a reading of these two entries from his site that clearly make the case for chemical treatment creating weaker bees and stronger mites. The breeding reliance on only some 600 commercial queen lines in the US has led to very inbred bees and created a genetic bottleneck. A quote from the Randy Oliver link—“There is some evidence that some lineages are innately more resistant to certain parasites [44]. The question that haunts me is to what degree our recent elevated rate of colony mortality might be due to the limited gene pool of our managed stocks, which may simply be lacking critical genes for resistance to the onslaught of our recently-introduced parasites and the associated virus issues. Such a problem would likely be self correcting if it weren’t for the nearly universal reliance upon medications by our queen producers [45].”

“Perhaps of most practical application: a recent study by Tarpy [46] found that colonies that were less genetically diverse were 2.86 times more likely to die by the end of the study when compared to colonies that were more genetically diverse. This raises the serious question of whether our managed bees are a bit too inbred.”

There is much to be learned from these two links that the piece I am commenting on fails to take into account in any way.

http://scientificbeekeeping.com/whats-happening-to-the-bees-part-5-is-there-a-difference-between-domesticated-and-feral-bees/

The tradeoffs in fitness that we have inadvertently forced in the stock of honey bees used worldwide in the First World is examined in this link—-

http://scientificbeekeeping.com/whats-happening-to-the-bees-part-6-mitotypes-genotypes-and-tradeoffs-in-fitness/

One must remember that the commercial purchase and traffic in “bred bees” is a fairly recent human endeavor. For most of human history—and still in the greater part of the world where pastoralists practice beekeeping (Central America, Africa, SE Asia) —bees being used were caught from the local survivor stock. This is what we are doing in Southern California with the resilient feral stock widely available. No less a eminent entomologist as Thomas Seeley has been writing recently of the concepts of returning to a Darwinian informed model of beekeeping to overcome the weaknesses of highly selected stock.

LikeLike

Hello Susan,

Thank you for commenting. You make excellent points, and it seems to me that you are clearly participating in a type of realistic breeding program, as called for in the quote I included from Randy Oliver – with the insight that what is needed is a wider genetic base, and through that, greater resistance to Varroa mite can be achieved. This then can lessen the reliance or abolish the need for treatment entirely. The main point I was trying to make in the piece, was that simply overwhelming common bees vulnerable to Varroa as the initial ‘method’ does more harm than good, and is very unlikely to result in new adaptations. It is the commitment to a meticulous breeding program that will enable the goal of not needing treatments, not the commitment to not treating that will enable resistance.

I am very worried by what I hear about hobby beekeepers who simply allow varroa to collapse their hives, resulting in pest pressure on their neighbours that is too great even for somewhat more resistant bees to handle. I have also heard of a survey of commercial bee producers showing that 22 out of 30 now refuse to sell to hobbyists, because they will simply come out for more packaged bees in the next year, all their previous bees having died during the year. The remaining 8, perhaps even more worryingly, continue to capitalize on the frequently returning customers – just as you mentioned, this is what is problematic, not people who are involved in bee breeding and have as their goal not to need treatments. My piece draws attention to the problematic practice of *allowing Varroa mite free rein*, not to beekeepers breeding better lines that *can keep Varroa under control* (or stay Varroa free altogether).

Tom Seeley, too, from what I have read, represents this kind of a responsible way to approach the problem – monitoring and making sure that colonies do not go through high levels of varroa infestations, while finding lines of bees that are not as inbred and have more variance in their ability to resist Varroa to begin with. I hope his and your approaches can help sway the culture from a focus on treatment as inherently bad, to one with a renewed interest in bee genetics.

From Tom Seeley:

“I want to stress that it is not a recipe for let-alone beekeeping. Indeed, it requires diligent beekeeping, especially in monitoring colonies for high levels of Varroa and preemptively killing colonies that develop skyrocketing mite populations. Doing so selects against colonies without resistance to Varroa, it creates selection against highly virulent mites, and it prevents resistant colonies from getting fatally flooded with Varroa from the neighbors.” http://beeaudacious.com/index.php/2017/02/14/report-back-tom-seeley/

I couldn’t agree with him more. Thanks for underscoring the important concept of bee genetics with your comment.

I appreciate you stopping by, and I am happy to know that you are involved in the important work of breeding a wider genetic base to honey bees.

Happy Easter,

Iida/Thoughtscapism

LikeLike

No, there is a misunderstanding here. I am NOT engaged in any type of breeding program. There are no isolated DCAs, no queen selections/culling, no mite monitoring. Like many in the educated TF movement, we are using locally obtained survivor stock that has self-selected for varroa resistance through the Darwinian concepts of adaptation to selective pressure. Varroa arrived sometime in the ’90s and the local, abundant feral stock went through the die-off expected when a virulent pathogen and its vector arrive.

Again, I emphasize, these bees ALREADY manifest strong resistance to V.d. as evidenced by their large feral colonies established for years in structures throughout the LA basin. Colonies like this, as Randy Oliver points out (did you read the links I sent??) are not the result of absconding package bees riddled with mites, bees dependent on human applied chemical treatments. Such mite laden colonies do not make true swarm trajectories, but are ABSCONDING colonies. (if you are not a beekeeper, you many not know the term) They do not have the vitality or genetics (“fitness”) to become “founder colonies” as Randy names robust swarm established hives. Contrary to the mantra of the conventional bee world—using chemicals that impact the fertility of the queen, the health of the brood and the drones, and the gut ecology of bees— there are a lot of thoughtful, respected and long term beeks very successfully using survivor stock bees in all climates and not propping them up with chemical treatments. Please see the work of Kirk Webster, Sam Comfort, Michael Bush, or Dorian Pritchard— to name just a few. Why is there no indication in the piece written that any of these sources were reviewed?

The one criticism I would have with the writings of Tom Seeley is that in none of his pieces has he mentioned the importance of knowing the genetics of the stock one is using. By failing to articulate that package breeder stock is NOT the same as local survivor stock, too many people, the ones identified as “hobbyists” simple pull the meds from stock genetically dependent on supports and have bees that continually die.

I want to point out this common fallacy from the piece—“…or stay Varroa free altogether” is NOT the way of Nature. A organism does not develop and continue to manifest resistance to a pathogen by being totally free of the immune response caused by that pathogen. This is a artificial situation. Apis cerana, the original host of V.d., does not exist in isolation from the mites but in stasis. Your own body is constantly exposed to various pathogens and the immune response challenge is a practiced exercise of your system. Varroa IS in our colonies but at a well managed, background stressor population. Thousands of organisms exist in a bee colony, some like SHB and Hive Moths, which beek fixate on as “bad guys” But strong colonies manage all these stressors. Again, I emphasize that—varroa resistance is not something that “..can be achieved” but is already manifest in the colonies many TF beeks are keeping. Please consider interviewing Solomon Parker—it seems most of the scholarship of the piece written above is “received wisdom” and not direct experience with the beekeeping world.

LikeLike

I’d like to agree with your proposal that hosts come to an equilibrium with their parasites, but at the same time, we don’t treat any other managed animals like this. Could you imagine a farmer allowing cattle or pigs to suffer or even die from any of the internal parasites they can contract because they’re trying to hasten evolution, because if that cow can’t fend off that intestinal parasite, it should just die? They treat for these things as good stewards of their livestock. Even more far fetched but in the same vein would be a dog simply being allowed to die of heartworm because, “if that dog can’t live with the heartworm, I don’t want it.”

The queens not being related to the workers in packages is really a non sequitur. In 6 weeks, that queen will be the mother of every bee in the hive regardless of the bees that came with the package.

Also, bees, in the end, do need the traits that make them commercially viable. Africanized bees don’t have nearly the trouble with varroa that European bees do, but of course they also don’t hoard honey, are meaner than %$#@#, and swarm a *lot*. All of these things make them a poor choice for a managed pollinator unless the climate is such that there are blooms year-round and the population is extremely sparse. The same can (but not always) go for hygienic behavior. There are reports of hives that are so hygienic that while they survive very well, they never get large enough to produce any kind of honey crop or be large enough to fulfill a pollination contract. The usefulness of the resulting bees has to be understood as a requirement, not just a nice-to-have.

Finally, I’d say that beekeeping is probably one of the most “hyperlocal” endeavors in agriculture. I applaud that you can be TF, I’m even totally jealous. But in my area (southern PA), this just isn’t possible most of the time. Even the few commercial beekeepers we have here who I know do excellent in selecting breeding stock have to treat many hives each year. I think the internet is a beekeeper’s best friend and worst enemy. Those who begin beekeeping as a hobby hear about people like yourself. Many of those new beekeepers will be in completely different climates and areas but still think, “Well, he/she can do it. I should be able to do it too.” That’s just not always going to be the case. While they’re trying to be treatment free, they’re producing mite bombs that explode every fall and cause more treatments to be necessary, here by those who wish to keep their bees alive over our cold winters.

LikeLike

Matt—the analogy with other industrial animal keeping is not apt. This comparison is made ALL the time by people not looking at the biology of insects. Bees fly from their hives to forage and prosper as they see fit. We do not control them, confine them or make them bend to our wishes. As well, the reproductive rate is more rapid and overall population density of arthropods is much greater than any of the named mammals you mention. Because of this, the ability to adapt to selective pressures from the environment and disease is enhanced.

Regarding the queen of packages not being related to the workers, there is a common couple issues with this—the bees often kill her or supercede her—so, what have you paid for?

Please read the links to the Randy Oliver articles I posted. Your security with the commercially available stock may be changed—a quote of particular interest—“The question that haunts me is to what degree our recent elevated rate of colony mortality might be due to the limited gene pool of our managed stocks, which may simply be lacking critical genes for resistance to the onslaught of our recently-introduced parasites and the associated virus issues. Such a problem would likely be self correcting if it weren’t for the nearly universal reliance upon medications by our queen producers [45].

Perhaps of most practical application: a recent study by Tarpy [46] found that colonies that were less genetically diverse were 2.86 times more likely to die by the end of the study when compared to colonies that were more genetically diverse. This raises the serious question of whether our managed bees are a bit too inbred.”

….the nearly universal reliance upon medications…. Mite resistance is ongoing

As to this assertion “Africanized bees don’t have nearly the trouble with varroa that European bees do, but of course they also don’t hoard honey, are meaner than %$#@#, and swarm a *lot*. All of these things make them a poor choice for a managed pollinator unless the climate is such that there are blooms year-round and the population is extremely sparse.” Have you ever kept AHB or are you taking your information from the hoary and prejudicial “common knowledge” that gets bandied about? I keep AHB hybrids and find NONE of these assertions are true. The greater part of the southern US has AHB genetics (from the work of Dr Kerr in Brazil over 60 years ago) and some of the best bees to work for the Mediterranean climates come from these hybrids.

Since you express a wish to learn about TF beekeeping, know that there are scads of educated TF beeks in the Eastern US, (and PA) successfully using bees adapted to your local conditions. That is why the statement here is overlooking the points I made in the earlier post— ” Many of those new beekeepers will be in completely different climates and areas but still think, “Well, he/she can do it. I should be able to do it too.” Know the source and genetics of the bees you wish to hive! Look at the work of Kirk Webster (VT) Sam Comfort (NY) or Dorian Pritchard (England) None of these folks has the mild weather of Los Angeles, so you can’t hang the argument on that one.

LikeLiked by 1 person

by the way, there is a strong TF group presence here, with 14,000 worldwide members—https://www.facebook.com/groups/treatmentfreebeekeepers/

LikeLike

Can’t reply to your below comment Susan, not sure why.

I agree that insects reproduce much more rapidly than mammals, but the attitude is still somewhat the same. I searched and searched but I can’t find where Randy Oliver also stated that if a hive isn’t doing well managing its mites, that’s the genetics of that queen, it’s not those workers’ fault. So his advice there is to treat to rid that hive of its mites and requeen. Yes, you’re pinching a queen which is unfortunate and some might say cold hearted, but this is proper management. Letting a hive with poor genetics breed mites that it then spreads when it crashes is definitely not. If I find that post of his I’ll link it here.

I know there are TF beekeepers in PA, but not in my area of PA. No one’s been able to make it work here yet long term that I know of. In the wilds of PA, not too many hobby beekeepers who don’t treat and where there’s plenty of fall forage, the chances of TF I’m sure go up tremendously. We have over 65% agriculture and a successful fall flow for us is not having to feed. We make no fall honey where I am, there just isn’t enough forage. The nutrition game is stacked against us here, so our bees are at that disadvantage already. This along with many hobby beekeepers who do, in fact, let their hives crash in the fall because they just don’t believe that mites are the problem they are means being TF is all extremely difficult here. I’m certainly not a huge part of the solution. I select as best I can but it is just a hobby when I have a full time job. But I definitely do try to not be part of the problem.

LikeLike

I love the open approach Iida and I support your idea that blind idealism isn’t enough but like others I think the long term needs to be considered. Indiscriminate chemical use and reduced genetic diversity driven by short term economics has caused problems in past with fungus, weed and insect resistance and continues to do so. The same with bees. Relying on sugar supplements without the complex of unknown chemicals that bees have evolved with and keeping even the least resistant strains to make new hives can create problems now and for the future. Also – there is only one species of bee commonly kept in hives – Apia mellifera, the honey bee which has a number of sub-species. “ok if a number of bee species should die out” – do you mean species, subspecies or strains or maybe you are saying reduced genetic diversity? I believe, with you, that the key is good management, but as natural as we can manage, with intervention when required. What that means will vary massively from place to place and beekeeper to beekeeper.

LikeLike

Matt— the science does not back up the statement comparing industrial animals and insects that “…the attitude is still somewhat the same” From a link here https://projects.ncsu.edu/cals/course/ent425/text01/success.html

Under ADAPTABILITY–

“A combination of large and diverse populations, high reproductive potential, and relatively short life cycles, has equipped most insects with the genetic resources to adapt quickly in the face of a changing environment. Their record of achievement is impressive: ”

The quote from Randy Oliver’s Part 5 piece is essentially stating what you say here “Randy Oliver also stated that if a hive isn’t doing well managing its mites, that’s the genetics of that queen, it’s not those workers’ fault.”

RO’s writing— targeting queens—

“Such a problem would likely be self correcting if it weren’t for the nearly universal reliance upon medications by our queen producers” [45].

One of our most eminent TF writers is Michael Bush who lives in the heartland of mono-crop corn production in Nebraska. He is surrounded by miles of nothing but heavily sprayed and managed corn. He wrote the book “the Practical Beekeeper—Beekeeping Naturally” You can read the entire book on line (no purchase of the hardbound copy required) at http://www.bushfarms.com/bees.htm

A very interesting numerical examination of the “effectiveness” of chemical treatments is here—http://www.bushfarms.com/beesvarroatreatments.htm

I wonder if you posted a note at the TF facebook group site I noted above if you would not find a TF beek or two in your area. No harm in asking. That’s how a lot of folks from all over the world find the others. We have beeks from Bulgaria, Iceland, Sweden, Nigeria, Bangledesh, Thailand etc. asking for links to like-minded beeks via our FB group

LikeLike

Dr. Eric Mussen of UC Davis, State Apiarist for California for decades, called the “Treatment Free” approach “Nuisance Beekeeping”, and the results are exactly what one would expect where one is weak on the husbandry part of Animal Husbandry.

Beekeepers who hope that this fad will be a self-correcting problem underestimate the attraction of clickbait pitches to millennials with deficient math and science education, similar to “Veterinarians hate this one weird trick that saves you money!”, or the staying power of the charlatans who “educate” others for dubious fame and trivial fortune on this highly speculative approach, which rejects the “keeping” part of beekeeping as harmful. If not for the internet, these practices would have never spread beyond the first few dead hives.

But these earnest folks honestly believe that, despite honey bees having remained essential unchanged for the past 130 million years, they can some how re-route the course of evolution, two dead hives at a time.

LikeLike

Y.A.B.—these remarks are not only a indication of not having any biological knowledge of the adaptation of organisms to evolutionary pressures, but there are NO citations for any of the subjective assertions about keeping bees without human devised chemical treatments. Making references to modern human cultural phenomenons only makes the assertions more suspect. As well, your statement about Apis mellifera evolutionary records is way off—according to Tom Seeley, entomologist at Cornell Univ—“The oldest fossil honey bee is only about 30 million years old (from lignite shales in Germany), and it is Apis henshawi, not Apis mellifera. The oldest fossil Apis mellifera are in copal (fossilized tree resin) from Africa. These fossils are at most only 1.7 million years old. So the best we can say for now is that the genus Apis is more than 30 million years old, and that Apis mellifera is probably at least 1.7 million years old.

LikeLike

as someone who is just starting off as a beekeeper, i appreciate all the various viewpoints on “proper” ways to manage bees. But i have to say, that I am sorely dissapointed by those promoting the general “consensus” that “the science is settled” it when it comes to reasons for demonizing treatment free beekeeping

After taking an introductory course to beekeeping and receiving my Master Beekeepers Apprerentice, I never once was introduced to any alternative theories or solutions regarding varroa. There was no discussion of possible causes – just the “necessary” solutions which all involve are a myriad of chemicals that we are to accept will only work until the pests create a resistance.

I’m of the camp which accepts that beekeeping is by its nature, not “natural”. It’s almost an oxymoron to me to suggest it is. However, is it any less natural than raising livestock which we’ve learned over time to raise without antibiotics, monocrops, and hormones?

It seems that the mainstream (government science agencies) approach to beekeeping is always treatment. Where is all the science discussion at least about other possible factors? I.e. industrializatin of beekeeping, queen rearing, perpetuation of drug resistance, etc.

I came at this knowing nothing, but the most compelling arguments to me are from those like Lusby and Parker and not being dogmatic, I do see legitimacy in arguments on both sides but will choose to be “part of the problem” i guess, by taking the treatment-free, natural cell size approach.

LikeLike

I’m wondering at what point bees can be considered mite-resistant. 3 years with no treatments? 4? In order start a breeding program for mite resistant bees, there must first be bees monitored & left without treatment to identify which bees are resistant. Then, once those are identified a breeding program can take place. It seems as though the first step to a successful breeding program is what you are advocating against. In other words, you need to first have treatment free bees in order to breed bees that don’t require treatment for varroa.

LikeLike

Pingback: Are Honey Bees Dying - Are We Losing Our Food Supply? - Garden Myths

By the way, you can find a less dogmatic crew of practicing, aspiring and/or transitioning Treatment Free type beekeepers in the “Reasonably Treatment-Free Beekeepers” Facebook Group:

https://www.facebook.com/groups/1394858203868544/

I

LikeLike

Thanks. I see the person posting my piece on your FB group reasonably assumed I must be a paid shill for Monsanto or Syngenta right off the bat.

Sorry for the sarcasm, but in my defence that insult gets very old very fast. If someone criticises a view one holds, it is very intellectually dishonest (and overly convenient) for the person who is a proponent of that view to simply make up a reason for why they get to dismiss all the evidence.

I raised concern over the content of the pieces I read from beekeepers in the context of the evidence on the spread of Varroa mite, not for purpose of ridicule, but for the purpose of highlighting potential reasons why hobby beekeepers have so much higher levels of Varroa mite, as documented by the literature. I do this on my free unpaid time to promote a more scientific perspective on saving the bees. Beekeeping methods too should rely on the best possible evidence, and I make sure no one has to rely on my word on that – but I refer them to that evidence instead.

I am glad you do not forbid discussing treatments or other topic in your group. For longer answer, please see my response to your later duplicate comment.

Iida/Thoughstcapism

LikeLike

The beekeeper referred to in this article as “a TF blogger from Vermont” is Kirk Webster, who has been keeping hundreds of hives without varroa treatments for well over a decade now, and making a decent living from his beekeeping endeavors, producing considerable numbers of nucs and queens for sale each year, as well as honey. During this time he has also written numerous articles in the two leading bee journals here in the U.S., (Bee Culture and American Bee Journal), describing his methods, which have included using (partially) varroa-resistant Russian honey bee stock that was originally imported and developed by USDA scientists in conjunction with cooperating beekeepers. He has continued to develop the stock since then, with his own careful selective breeding program, and an “expansion model” based on raising and overwintering large numbers of nucleus hives.

In short, Kirk is doing exactly the kind of thoughtful, diligent treatment-free beekeeping that this article purports to support — the kind that involves a purposeful and realistic management and breeding plan to allow the beekeeper to keep bees healthy and productive without varroa treatments. Unfortunately the author of this article didn’t include any of this context, they simply refer to Kirk as “a TF blogger from Vermont,” and quoted a few out-of-context phrases from of his writings, apparently selected mainly for ridicule purposes. (And yeah, some of the philosophical “big picture” stuff in Kirk’s writings is a bit on the woo-woo / crunchy granola side for me too. But any actual examination of his methods, or indeed any actual conversation with the guy — and it’s pretty clear the author of the above article did not attempt either of these — would quickly reveal that Kirk has a strong grounding in both the science and the practicalities of beekeeping.)

This is all extremely unfortunate, since the author raises some very important points about the potential undesirable effects of a blindly dogmatic “just don’t treat them, ever” mindset that doesn’t involve a thoughtful approach to management and breeding. Unfortunately the author undercuts their own credibility with such a ridiculously superficial and context-divorced reference to “a TF blogger from Vermont.” This leads me to wonder if other aspects of the article, aspects which I am not as familiar with and therefore not in as good a position to judge, are equally superficial and distorted.

I don’t purport to be an expert on Kirk’s methods, but I was fortunate to have the opportunity to visit Kirk in the spring of 2015 on one of his “Field Days,” where he invites beekeepers to come have a look at his operation and learn a bit more about how he goes about managing, breeding and propagating his bees. I can assure you, there is nothing slipshod or haphazard about his operation, he is not just closing his eyes and hoping for the best, he’s deliberately and thoughtfully pursuing a strategy for sustaining and improving his stock. It’s not always easy, and he has had high winter losses some years (of course so do many heavy-treatment beekeepers) but overall his approach appears to be pretty successful. He’s certainly not getting wiped out and then making up his numbers by re-stocking his hives with package bees from the south, as many beekeepers in the Northeast (treaters and non-treaters alike) end up doing.

But the author does not need to take my word on it — they can go see Kirk’s operation and talk to Kirk in person during his upcoming Field Day on July 22nd. There is no charge, and no pre-registration is required…all you have to do is show up (and bring a bag lunch). If the author is interested in seeing an example of a smart, diligent approach to keeping bees healthy and productive without varroa treatments — and witnessing an operation with a considerable track record of success in doing so, I strongly recommend it. While you’re there, feel free to ask Kirk to explain what he means when he says that he now considers varroa an “ally” of sorts — that struck me as provocative as well, but makes a lot more sense when you understand the full context (I will refrain from offering my interpretation here, out of concern that I may not get it quite right).

Should a trip to Vermont be impractical for the author, I would suggest that the author try calling Kirk or writing him a letter — because despite the description “a TF blogger from Vermont,” Kirk doesn’t appear to spend much (if any) time online, in fact he doesn’t even do e-mail (at least not last I heard), he doesn’t do Facebook groups, and the so-called “blog” is just a website hosted by some friends of his who have posted his writings there.

Unlike the surprising number of beekeepers who seem to spend most of their time furiously blogging for or against TF beekeeping, while actually having very few hives and in many cases very few years of experience, Kirk actually has a whole lot of hives to look after, and a lot of queens and nucs to raise, and doesn’t spend his time in the blogosphere or Facebook, haranguing others on how they must treat or must not treat because otherwise they’re bad beekeepers.

For more info on the July 22 Field Day, contact information to call or write to Kirk, and for his collected writings (which is obviously the first place to start if you want to get a better understanding his methods), you can go to this website maintained by some of Kirk’s friends:

http://kirkwebster.com/

– Garrett Brinton

LikeLiked by 1 person

Not sure why this comment hasn’t made it through moderation, but I’ll try again…

The beekeeper referred to in this article as “a TF blogger from Vermont” is Kirk Webster, who has been keeping hundreds of hives without varroa treatments for well over a decade now, and making a decent living from his beekeeping endeavors, producing considerable numbers of nucs and queens for sale each year, as well as honey. During this time he has also written numerous articles in the two leading bee journals here in the U.S., (Bee Culture and American Bee Journal), describing his methods, which have included using (partially) varroa-resistant Russian honey bee stock that was originally imported and developed by USDA scientists in conjunction with cooperating beekeepers. He has continued to develop the stock since then, with his own careful selective breeding program, and an “expansion model” based on raising and overwintering large numbers of nucleus hives.

In short, Kirk is doing exactly the kind of thoughtful, diligent treatment-free beekeeping that this article purports to support — the kind that involves a purposeful and realistic management and breeding plan to allow the beekeeper to keep bees healthy and productive without varroa treatments. Unfortunately the author of this article didn’t include any of this context, they simply refer to Kirk as “a TF blogger from Vermont,” and quoted a few out-of-context phrases from of his writings, apparently selected mainly for ridicule purposes. (And yeah, some of the philosophical “big picture” stuff in Kirk’s writings is a bit on the woo-woo / crunchy granola side for me too. But any actual examination of his methods, or indeed any actual conversation with the guy — and it’s pretty clear the author of the above article did not attempt either of these — would quickly reveal that Kirk has a strong grounding in both the science and the practicalities of beekeeping.)

This is all extremely unfortunate, since the author raises some very important points about the potential undesirable effects of a blindly dogmatic “just don’t treat them, ever” mindset that doesn’t involve a thoughtful approach to management and breeding. Unfortunately the author undercuts their own credibility with such a ridiculously superficial and context-divorced reference to “a TF blogger from Vermont.” This leads me to wonder if other aspects of the article, aspects which I am not as familiar with and therefore not in as good a position to judge, are equally superficial and distorted.

I don’t purport to be an expert on Kirk’s methods, but I was fortunate to have the opportunity to visit Kirk in the spring of 2015 on one of his “Field Days,” where he invites beekeepers to come have a look at his operation and learn a bit more about how he goes about managing, breeding and propagating his bees. I can assure you, there is nothing slipshod or haphazard about his operation, he is not just closing his eyes and hoping for the best, he’s deliberately and thoughtfully pursuing a strategy for sustaining and improving his stock. It’s not always easy, and he has had high winter losses some years (of course so do many heavy-treatment beekeepers) but overall his approach appears to be pretty successful. He’s certainly not getting wiped out and then making up his numbers by re-stocking his hives with package bees from the south, as many beekeepers in the Northeast (treaters and non-treaters alike) end up doing.

But the author does not need to take my word on it — they can go see Kirk’s operation and talk to Kirk in person during his upcoming Field Day on July 22nd. There is no charge, and no pre-registration is required…all you have to do is show up (and bring a bag lunch). If the author is interested in seeing an example of a smart, diligent approach to keeping bees healthy and productive without varroa treatments — and witnessing an operation with a considerable track record of success in doing so, I strongly recommend it. While you’re there, feel free to ask Kirk to explain what he means when he says that he now considers varroa an “ally” of sorts — that struck me as provocative as well, but makes a lot more sense when you understand the full context (I will refrain from offering my interpretation here, out of concern that I may not get it quite right).

Should a trip to Vermont be impractical for the author, I would suggest that the author try calling Kirk or writing him a letter — because despite the description “a TF blogger from Vermont,” Kirk doesn’t appear to spend much (if any) time online, in fact he doesn’t even do e-mail (at least not last I heard), he doesn’t do Facebook groups, and the so-called “blog” is just a website hosted by some friends of his who have posted his writings there.

Unlike the surprising number of beekeepers who seem to spend most of their time furiously blogging for or against TF beekeeping, while actually having very few hives and in many cases very few years of experience, Kirk actually has a whole lot of hives to look after, and a lot of queens and nucs to raise, and doesn’t spend his time in the blogosphere or Facebook, haranguing others on how they must treat or must not treat because otherwise they’re bad beekeepers.

For more info on the July 22 Field Day, contact information to call or write to Kirk, and for his collected writings (which is obviously the first place to start if you want to get a better understanding his methods), you can go to this website maintained by some of Kirk’s friends:

http://kirkwebster.com/

– Garrett Brinton

LikeLike

Hello Garret,