Perhaps you’ve seen one of these videoclips: the scene opens up of wolves galloping in the snow, then landscapes of rivers and mountains opening up before you. Pictures of deer and elk, bears, bison, beavers, badgers, foxes, eagles, and so on, are paraded before us to beautiful music. They are all told to be living again in harmony and balance, thanks to one factor: wolves. You hear the exalted voice of George Monbiot saying things like “Birds began to return to the park!” and “But this is where it gets truly remarkable, it turns out that reintroduction of wolves even changes the course of rivers!”

Large predators are an important part of upholding the balance of ecosystems, for sure. But does an ecosystem “miraculously” return back to normal, including its physical landscape, by introduction of one of its main predators, 70 years after its removal?

Uplifting videos, like the ones produced by the Sustainable Human and the National Geographic, certainly do a good job convincing us that this is what has in fact happened. They are truly lovely (if a tad melodramatic) stories, too. But I think they would be better if they were accurate.

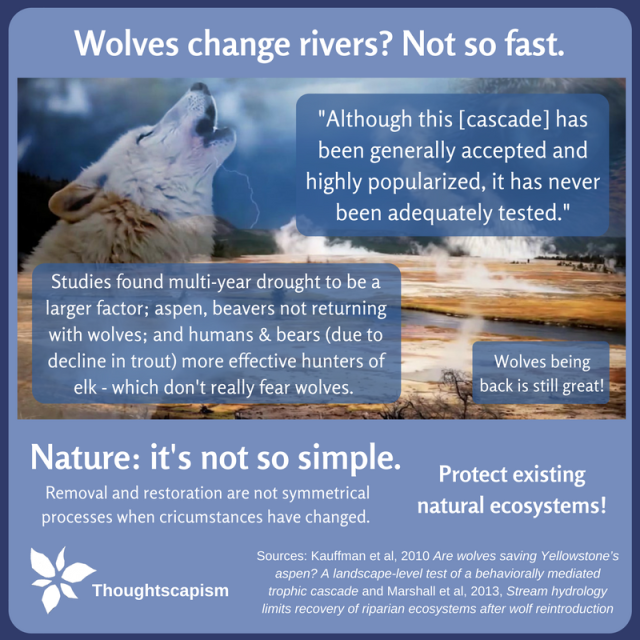

When I started reading more about this fantastic phenomenon of wolves in Yellowstone restoring the entire habitat to its former glory, what I found out was that this inspirational story does change the course of several lines of evidence on the workings of the Yellowstone ecosystem, in order to make its message simple.

As the 2010 ecology paper Are wolves saving Yellowstone’s aspen? A landscape-level test

of a behaviorally mediated trophic cascade puts it,

Although this BMTC [behaviorally mediated trophic cascade] has been generally accepted and highly popularized, it has never been adequately tested.

National Geographic (screenshot here) and George Monbiot suggest this sparked a vast and dramatic change remarkable enough to change rivers

The paper found that aspen trees were not in fact recovering in the Yellowstone even in the presence of wolves, partly because wolves are not a big enough threat to the elk.

Another paper from 2013, which performed a decade-long experiment in Yellowstone, titled Stream hydrology limits recovery of riparian ecosystems after wolf reintroduction found that wolf reintroduction have not lead to return of beavers or increase in willow growth.

Beavers could, in fact, change landscapes

They suggest that disappearance of beavers, unfortunately, is a catch-22-like factor in that it creates a natural hinder to their reintroduction:

The current state of the landscape is resilient to the trophic effects of wolf restoration because the absence of beaver opposes the return of tall willows and the absence of tall willows opposes the return of beaver.

Simply reintroducing wolves does not seem to make a great impact in the landscape that used to be maintained by the populations of beavers. Willows remain small, and beavers remain absent. This shows the value of maintaining ecosystems, because putting them back together again will not be quite as simple (still from the 2013 paper):

The frequency distribution of willow heights closely resembles the distribution observed before wolves were reintroduced (figure 4). Landscape-level restoration of historical conditions in willow communities is opposed by hydrological changes in the riparian zone caused by beaver’s continued absence. Our results amplify the fundamental importance of conserving intact food webs because changes in ecosystems caused by removal of apex predators may be resilient to predator restoration.

Spreading evidence-based, nuanced views is an uphill battle

These complexities in the interacting network of factors behind the Yellowstone ecosystem have been highlighted by scientists in the media before. Unfortunately these stories don’t appear to reach the same kind of audience as do the inspirational videos.

Here, an example from PBS Did wolves help restore trees to Yellowstone? interviewing wildlife ecologist Dan MacNulty:

“The question is: Do these changes have anything to do with the wolf reintroduction?” […] that’s a tough link to prove, because there are so many environmental variables at play. Most significantly, a multi-year drought was in full swing right around the same time as the wolf reintroduction. Aspen and willow trees need a lot of moisture to grow. In fact, MacNulty says there has been a long-term drying trend in Yellowstone since records started to be kept in the late 1800’s.

It’s a source of active debate and there is no consensus on whether the aspen decline was caused by long-term drought, over-browsing by elk, or a combination of the two, MacNulty said.

The field biologist Arthur Middleton, who has published observations on the dynamics of Yellowstone predators and prey, elaborates about the relationship between elk, wolves, and other predators, quoted in this blog piece by an animal behaviour writer, Maybe Wolves Don’t Change Rivers, After All:

A few small patches of Yellowstone’s trees do appear to have benefited from elk declines, but wolves are not the only cause of those declines. Human hunting, growing bear numbers and severe drought have also reduced elk populations. It even appears that the loss of cutthroat trout as a food source has driven grizzly bears to kill more elk calves. Amid this clutter of ecology, there is not a clear link from wolves to plants, songbirds and beavers.

Does this all mean that wolves don’t matter? Of course not. Wolves are an integral part of many ecosystems, and their disappearance from the world would be a great loss. I heartily second the update on the top of that same blog post:

ecological researchers agree that reintroducing wolves to their former home range across the American West is a major benefit to wildlife and healthy habitats. It is also essential. All this article says is that the results are not as quick or simple as some environmentalists want to believe

In fact, probably good NOT to expect miracles. Let’s not promise them either. Screenshot of the Natural Geographic and Newsner videoclip.

It is wonderful that wolves have returned. Perhaps further evidence will come to light supporting a stronger link between wolf predation and other ecosystem effects – that would be great, and it would be fascinating to read more about actual confirmed effects.

Meanwhile, re-wilding and re-introduction are valuable efforts, even when their results are perhaps not as miraculous as suggested. They can make a big difference where species or entire ecosystems have been lost. I’m all for supporting efforts of restoring ecosystems, and apex predators can help achieve those goals in many ways. But it may well backfire if we promise magic or miracles as a result from a few simple actions, like these videos have done.

For a more of my articles on the topic of environment, please look here. If you would like to have a discussion in the comments below, please take note of my Commenting policy. In a nutshell:

- Be respectful.

- Back up your claims with evidence.

We like simple answers, simple solutions, clean narratives. We like to hear stories that verify our ethics and belief systems. Its difficult to remain critical in such occasions. Its like you really want this video to be true.

Truth is Nature is wonderful to observe and study without the anthropomorphic characteristics we feel that we ought giving it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

RE: Spreading evidence-based, nuanced views is an uphill battle

Hi all

The same kinds of stories are told regarding the impact (or not) of the so-called “invasive” honey bee. A new paper out contends that honey bees do ecological damage *even* where they are native. These views are based primarily on conjecture and are tainted by bias.

See: Conserving honey bees does not help wildlife; High densities of managed honey bees can harm populations of wild pollinators. SCIENCE • 26 JANUARY 2018 • VOL 359 ISSUE 6374

BUT SEE: Mallinger RE, Gaines-Day HR, Gratton C (2017) Do managed bees have negative effects on wild bees?: A systematic review of the literature. PLoS ONE 12(12)

LikeLike

The wolf researcher David Mech’s “Sanctifying” paper did probably more than anything else to debunk the myths. https://www.scribd.com/doc/104750776/333-is-Science-in-Danger-of-Sanctifying?secret_password=35hwawnibboc5yb6gjm

Anytime I read the word “balance” to describe nature or any facet of nature I’m very leary. Nature is not balanced nor are ecosystems. Yellowstone is what it is today because that’s what we chose to make it. There is no possibility of return to yesteryear, we are in today and tomorrow will too be different.

LikeLike