Whenever nuclear power comes up in discussions online, more often than not someone declares that all anyone needs to know can be said with one word: Chernobyl. This name evokes a chilling reaction in most of us, and the idea is that this should conclude the conversation. There can be no argument heavier than “What about Chernobyl?”

A ‘radioactive’ sign hangs on barbed wire outside a café in the ghost-town of Pripyat near Chernobyl.

Can there?

I’ve spent a lot of time trying to understand the impacts of Chernobyl nuclear disaster, as well as the overall effects of different energy forms on human health and the environment. I often try to make the argument that we should look at the big picture, the totality of the effects, at first hand.

But the big picture is vague, grey, and complex. The name of that place – Chernobyl – and the accident it’s irrevocably linked with, burns with a bright red focus in people’s minds. Chernobyl disaster might be the most famous accident in the world. It would definitely be wrong to sweep its effects aside – the tragedy of lives and homes lost is real, painful, and unforgettable.

But here we arrive at an odds. Do the lives of the people affected by the Chernobyl accident weigh more than the lives of people struck by man-made disasters elsewhere? Should we respect the memory of the victims of Chernobyl more than those who died as the result of the failures of other energy forms?

That does not seem to make sense. What about workers and their families who were killed and whose homes were destroyed by gas explosions or coal mine fires, or the tens of thousands who have drowned after dam breakages? And what about the millions who die every year, in the non-accident that is the steady production of particulate air pollution?

Pictured: Banqiao dam failure, the Great London Smog, San Juanico gas explosion, and Soma coal mine fire. Soma photo is a black and white version of the original by Mustafa Karaman, used according to licence CC BY 3.0.

It may be difficult for people to look away from the dramatic, swift, and deadly events that large energy accidents are. It may feel cold and detached to contrast such tragedies with the constant trickle of lives lost to the business-as-usual burning of fossil fuels, even if those lives are not any less real.

If we were to argue that these were two distinct classes of effects, and we wanted to look at impacts of energy accidents separately, the question remains: how can we justify only using certain accidents as dire warning examples, as end-all type of arguments, while ignoring others?

Let’s look at whether Chernobyl should weigh heaviest out of all energy accidents because of its death toll. (Note: I’ll look at Chernobyl’s impacts on nature next, and put world’s worst energy accidents in environmental perspective in the final article.)

Chernobyl in context

Chernobyl accident directly cost 31 lives, and caused some 106 injuries, among the cleanup-workers and firemen. Further injuries include thousands of cases of thyroid cancer. UNSCEAR report, summary on page 64:

To date, some 6,000 thyroid cancers have been seen […] of which a substantial fraction is likely to have been due to radiation exposure.

Most of the cases are easily treatable and fatalities are expected to stay low – so far, 15 deaths from thyroid cancer have been connected to exposure from the accident. This figure may eventually reach 160 by the time the cohort has reached the end of their lifespan. That brings the eventual sum to near 200 deaths.

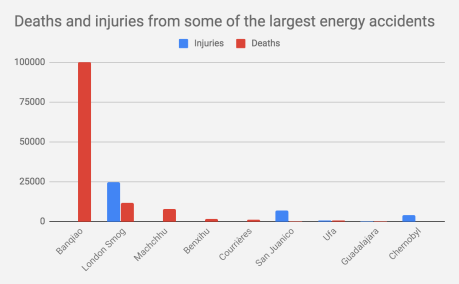

Direct deaths and injuries of 1975 Banqiao dam failure, the 1952 Great London Smog, 1979 Machchhu dam failure, 1942 Benxihu coal mine fire, 1906 Courrieres coal dust explosion, 1984 San Juanico gas explosion, 1989 Ufa gas explosion, 1992 Guadalajara gas explosion, and 1986 Chernobyl. (Note injury count not available for Banqiao, Machchhu, Benxihu, or Courrieres.)

If we compare direct death tolls of the largest energy accidents (graph), we quickly notice that there is one accident above others: the massive flood after the dam failure in Banqiao, China, in 1975.

Most people may not have heard of the accident, disturbingly enough, because the Chinese government did their best to contain all information about the disaster. It first became public knowledge after 30 years when the documents were declassified.

Banqiao flood is in a class of its own, with estimated death toll of 170,000-250,000 thousand. About 100,000 drowned directly (pictured in the chart), and as much or more died in the resulting epidemics and famine.

Dams harness formidable forces. Pictured: the biggest dam in the world, Itaipu in Brazil. Not an accident site.

There is no data easily available on the number of injuries, but 11 million people were left homeless as towns and villages were destroyed.

To get an idea about the relative sizes of the rest of the grave accidents, let’s remove Banqiao from the chart – its toll is so staggering it leaves everything else in its shadow.

The second-worst event took place in London – it was the Great Smog of 1952. Air pollution pooled over the city under problematic weather-conditions. Over ten thousand people died directly, and twice that number developed serious ill health-effects due to the smog.

Chernobyl is still not much more than one datapoint among others in this chart – a tragic, horrendous datapoint, to be sure, but by no means unique.

But pictured here are the more direct effects of the accident – the radiation poisonings and the thyroid cancer deaths so far, which scientists connect to the accident with good certainty. What about the more indirect, long-term effects of Chernobyl?

Realistic effects vs worst case scenarios

After the established 50 or so direct deaths and thousands of thyroid cases, the long-term effects on overall cancer risk become more speculative. As the risk consultant David Ropeik writes, in Fear of Radiation Is More Dangerous than the Radiation Itself:

Much of what we understand about the actual biological danger of ionising radiation is based on the joint Japan-US research programme called the Life Span Study (LSS) of survivors of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, now underway for 70 years. Within 10 kilometres of the explosions, there were 86,600 survivors – known in Japan as the hibakusha – and they have been followed and compared with 20,000 non-exposed Japanese. Only 563 of these atomic-bomb survivors have died prematurely of cancer caused by radiation, an increased mortality of less than 1 per cent.

I’ve written more about what we know about radiation exposures here.

The doses resulting from the Chernobyl accident were much lower. The extrapolation of effects on cancer incidence with such low doses is no longer considered scientifically justified, which is why the estimates of the other long-term effects from Chernobyl remain hypothetical. The hypothesis is that over the course of their natural lives, the populations who received an increased radiation dose near Chernobyl may have about 0.66 % added to their normal life-time cancer incidence of 40% – an increase on par with what we know about the effects of a couple of drinks of alcohol per week.

In 2005, based on this kind of extrapolation, the WHO and IAEA suggested that excess cancer fatalities could eventually number 4000. UNSCEAR has later refrained from quoting a figure, citing “unacceptable uncertainties in the predictions,” and underlined this extrapolation as a way of finding the theoretical worst case scenario, not a realistic one.

Not many energy accidents have these kind of thorough hypothetical analyses of the long-term effects exerted over the lives of those exposed (from exposures like smoke or poisonous gases from fires or explosions). But for the sake of the argument, let’s also look at the eventual and hypothetical death-toll of Chernobyl by the time the entire cohort has reached the end of their lifespan (still excluding Banqiao in this chart for resolution’s sake).

The worst possible outcome measured in health effects is that Chernobyl could qualify as the fourth gravest energy accident in history. Banqiao, 1975, the Great London Smog 1952, and Machchhu dam failure in Morbi, India, 1979, still caused thousands more direct deaths (no injury data or increase in eventual disease incidences available). The direct injuries of San Juanico gas explosion are also more numerous than the eventual ones from Chernobyl.

Update: a reader informed me of another large hydro accident in Italy, the Vajont Dam in 1963, leading to “1,910 deaths and the complete destruction of several villages and towns.”

If we were looking at single accidents as the end all, be all arguments, and the hypothetical death-toll of Chernobyl was the threshold of absolute opposition to an energy form, it appears that at least hydropower and coal, and possibly gas power, would also be out of the question.

These four together, by the way, at the moment represent about 60 % of the world’s energy sources.

What about repeat offenders?

Of course, here we run into the next problem – does it have to be a single large accident, or should we take into account how often such accidents occur? Looking at nuclear, the picture is not very complicated. There is only one nuclear accident that has claimed human lives over the history of the energy form.

What about Fukushima, you may ask? Well, while the tsunami killed almost 20,000 thousand people, radiation from the failed nuclear plant did not cause any casualties. The UNSCEAR conludes:

No discernible increased incidence of radiation-related health effects are expected among exposed members of the public or their descendants.

The evacuation, however, of the remaining Fukushima district was tragic. It was performed so hastily that many of the elderly and sick died – approximately 1600 people all in all. The decision was not based on the realistic risk from radiation, but on an inflated fear of it – sadly, Fear of Radiation Is More Dangerous than the Radiation Itself.

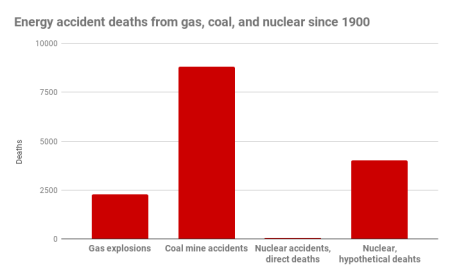

The picture is different for other energy forms. It is easy to find information about at least 26 grave gas explosions and 13 coal mine accidents that have occurred since the 1970s, resulting in 1492 and 1391 deaths, respectively. If we go further back, merely adding two of the largest coal mine accidents, those of Courrières, France in 1906, and Benxihu, China 1942, the toll climbs up to 4039 direct deaths for coal (and I don’t claim this list to be conclusive). How far back in the history of energy accidents should we go to make judgements for or against energy forms?

Comparing the lists of severe gas explosions and coal mining accidents to the nuclear accident since year 1900, the situation looks like this (chart). About 40 coal mining accidents have taken twice as many lives directly than the one nuclear accident ever will.

If we include the estimate of about 100,000-250,000 deaths from Banqiao, also adding Machchhu dam failure with its 10,000 victims, and compare them to the toll of coal mining, gas explosions, and the eventual nuclear fatalities all put together, they comprise but a modest piece of the tragic pie.

Why talk about accidents at all?

I have two major motives for bringing up these energy accidents. Firstly, it seems disrespectful to the victims that only some of these tragedies are looked upon with the austerity and respect they deserve. We should put names and images to these events, remember them, acknowledge that accidents come in many forms, and look for ways to reduce their number and impact.

Energy is, by nature, energetic: it makes things happen. When we loose control of these formidable forces, the things that happen are sudden and violent. We should have respect for energy in all its forms – the potential energy packed into vast masses of water, the chemical energy stored in combustible carbon compounds, as well as the nuclear forces within atoms themselves. None of these energy forms are without risk. I hope I’ve been able to show why fixating on Chernobyl alone is not warranted – that even the picture of energy accidents is complex and multifaceted.

The second reason, sneakily enough, is an attempt to bring us back to the argument I made in the beginning. Is a death more tragic if it happens violently, in one big flash together with hundreds or thousands of others – or whether it happens in hundreds of thousands of beds, hospitals, streets, or workplaces all over the world, day after day?

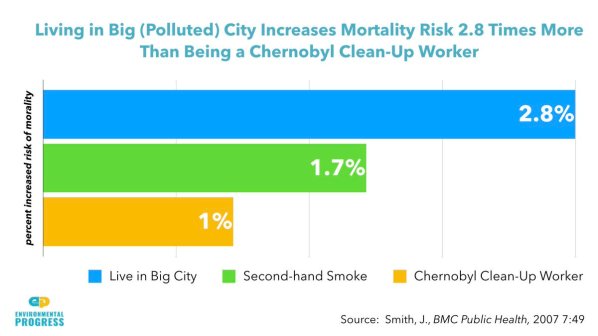

Environmental Progress’ Michael Shellenberger’s presentation of the findings of the 2007 study Are passive smoking, air pollution and obesity a greater mortality risk than major radiation incidents?

Is it ethically defensible to insist on focusing on hundred victims of a decades old disaster, while ignoring the millions who died this year because of the simple fact that they needed to breath air, which slowly damages their lungs with particulate pollution from burning stuff for energy?

Including the toll of the Chernobyl disaster, nuclear power has so far saved 1.8 million lives that would have been lost to air pollution from fossil fuels. If we value human lives, then all lives should matter – and if so, then we should move away from energy forms with the highest death-toll all in all. The data service Statista reports on energy forms in descending order of fatalities as follows: highest toll for coal, then oil, natural gas, hydro, rooftop solar, wind, and lowest toll, nuclear.

Considering that no energy form exists in a vacuum, climate scientist James Hansen and his colleague P.A. Kharecha published a paper in 2013, outlining the effects of nuclear power in Prevented Mortality and Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Historical and Projected Nuclear Power, concluding that nuclear power has saved a net total of two million lives by replacing energy that would have been produced by coal. Nuclear power continues to save about 80 000 lives per year, at current rate.

What about Chernobyl, you ask? Well what about Banqiao, London, Machchhu, San Juanico, Benxihu, Courrieres, Ufa, Soma, and Guadalajara? More importantly: what about the millions of human lives lost because our fears have stopped us from looking beyond that question?

The next part: “What about Radioactive Wastelands?” A Look at Chernobyl’s Effects on Nature – didn’t Chernobyl turn a huge swath of land uninhabitable? Finally I put World’s Worst Energy Accidents in Environmental Perspective.

For more articles on nuclear power and radiation, you can find my pieces under Climate and Energy. My largest worry used to be “What about the waste?” More about that in: Nuclear Waste: Ideas vs Reality.

If you would like to have a discussion in the comments below, please take note of my Commenting policy. In a nutshell:

- Be respectful.

- Back up your claims with evidence.

Hello Iida,

Thanks for putting the health impact of the Chernobyl accident in perspective. Very relevant indeed!

I would be interested to know if a similar analysis has been made of the financial impact of accidents with nuclear plants. Ideally such studies should incorporate an estimate of the economic value of the health loss (by assigning a value to the associated DALYs). Do you know if this idea has ever been explored?

Best regards

Han Joosten

microbiologist

LikeLike

I did this blog post 18 months ago. Might need a bit of updating if the Fukushima costs have gone up:

https://prismsuk.blogspot.com/2018/01/cost-of-nuclear-power-accidents-versus.html

LikeLike

Thank you very much for this very comprehensive article.

To be more complete I think one should add the uranium mining accidents. SDAG Wismut comes to mind, which was a uranium mine in East Germany under control of the USSR. According to Wikipedia there were 772 deaths associated with the mining operations. I have no idea how many fatal accidents in uranium mining happened elsewhere, but I don’ believe the death toll comes close to that of coal mining.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I have a minor issue with listing Banqiao as an “energy” accident. The dam was built primarily as a flood mitigation reservoir. The hydroelectric turbines were added because the dam was going to be there anyway, not as the primary use. That’s why the dam was so huge, many times bigger than would be needed just for hydroelectric power generation.

Having said that, I agree that the scaremongering over nuclear energy is not helping the discussion of how best to address climate change. Personally, I’d like to see a serious consideration of updated liquid salt reactors. They produce far less high level waste, the fuel is much less likely to be weaponised, and the risk of meltdown is all but eliminated.

LikeLike

Fascinating article supported with facts & figures. Perhaps the same methodology could be performed with the popular “safe energy” of “green”, solar & wind. I believe that the deaths from mining the necessary construction materials & installing the needed infrastructure, plus the eventual disposal after a much shorter life span vs. Nuclear, may increase the human fatality number. Reducing the overall safety of this energy source when viewed by the “Cradle to Grave” approach. Also might address the adverse impacts to wildlife.

LikeLike

You are comparing the deaths caused by nuclear energy vs other means of achieving energy.

But only toward the end I see that the number of deaths is compared to the amount of gigawatt produced.

In particular, I found misleading the graph “Energy accidents deaths … since 1900”, because I expect nuclear energy to have contributed less gigawatts than coal etc.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Here are a few webpages that address the issue of how many deaths per unit energy produced.

https://www.nextbigfuture.com/2016/06/update-of-death-per-terawatt-hour-by.html

https://ourworldindata.org/what-is-the-safest-form-of-energy

https://www.statista.com/statistics/494425/death-rate-worldwide-by-energy-source/

LikeLike

Hello, great piece.

That said, I think you should add the Ufa train disaster, in which an explosion following a leak from an lpg/methane pipeline killed 575 people and injured more than 800 ( https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ufa_train_disaster ), to the gas-linked accidents. Although not directly linked to a particular power plant, it’s safe to assume the pipeline supplied (or is still supplying, I can’t find more precise information on that particular pipeline) at least some power plants.

LikeLike

Sorry, my fault for not looking closely at the graphs, I just noticed that Ufa is indeed in there.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great article! Still, I believe the issue with Chernobyl and, possibly Fukushima, was not the death or/and injuries toll that were actually incurred. The issue was the potential for an even bigger and scarier outcome if certain measures were not taken. If, for example, they had not removed the water from underneath the reactor core, what would have been the outcome? Add this to the fear-mongering of these years, with the food curtails for example, due to possible radiation poisoning and you can understand why Chernobyl was such a big issue. Some even point the finger to the accident as a good starting point to the collapse of the USSR. Not one of the real issues, of course, but one good starting point of the cracks that brought the collapse.

LikeLike

One may argue that while accidents produced from fossil fuels/hydro plants are one-off events, nuclear accidents like Fukushima require expensive management for years, perhaps decades. The impact on the population is limited because billions of dollars are poured into nuclear post-accidents management and waste containment. Fukushima accident is not closed yet. How to factor that in your analysis? Thank you in advance.

LikeLike

Hello Dario,

Thanks for your interest in my blog and for your thoughtful question. To start off, it’s important to note that several huge dam breakages as well as oil leaks have been estimated to be much more costly than the worst nuclear accident ever, Chernobyl. If you are interested, there’s an older article on the costs of accidents here:

https://io9.gizmodo.com/what-is-the-worst-kind-of-power-plant-disaster-hint-i-5783526

To mention a few large costly accidents that were not covered by the above article, perhaps because they have impacted the environment more direly rather than taking as many human lives (I look at them here, https://thoughtscapism.com/2019/05/08/worlds-worst-energy-accidents-in-environmental-perspective/ ) I’ll mention 2 oils spills:

Deep Water Horizon and ExxonValdez have clean-up costs in the billions, they require decades-long restoration projects and many species have still not recovered even after 20-30 years. DeepWater Horizon has cost many times as much as the Banqiao dam failure, the company paying 65 billion dollars in cleanup and penalties (as much as 20 billion out of that might have been pure penalties) https://uk.reuters.com/article/uk-bp-deepwaterhorizon/bp-deepwater-horizon-costs-balloon-to-65-billion-idUKKBN1F50O6.

Now lets look at the Fukushima accident: it released very small amounts of radiation into the environment, so small that no health or environmental impacts have been seen or are to be expected. Yet it might end up costing even more than Deepwater Horizon! (I am not entirely sure how much the tsunami costs play in here, which should be separated from the nuclear accident costs.) How come? There are important factors to consider on the political nature of the decisions to invest in excessive remediation of the area, vs the physical or health grounds to do so. The Japanese officials have pledged to restore Fukushima to its previous levels of background radiation, for which there are no scientific rationalisations. The area is naturally a place with very very low levels of radiation. Most areas of the world would in other words, be ‘unclean’ by these standards, and require remediation, because the global averages lie markedly above the general levels in Fukushima. However in Fukushima, the government is scraping off vast areas of fertile topsoil (!) because it is somewhat more radioactive than before, never mind that it is worlds away from levels that would pose risk to anyone, or that would be unusual on global standards.

Side note, I am also very involved in discussions about environmentally friendly methods of agriculture, and maintaining soil is vitally important there – exposing soil layers to needless erosion is one of the most harmful things to do, never mind happily *scraping* it away…! This decision in Fukushima is so senseless and sad it blows my mind. It is also very costly.

There are many of these kind of examples that demonstrate the irrational nature of common attitudes toward radiation and nuclear power here. The Japanese officials also won’t release perfectly safe water from holding tanks out of fear, not of radiation, but of the impact on public image – you can read more about that in the excellent report from Mothers for Nuclear on their recent trip to Fukushima. https://www.mothersfornuclear.org/our-thoughts/2018/2/8/firsthand-in-fukushima

Another example is how Greenpeace thinks radiation that is normal for people living in Finland should elsewhere merit an evacuation. It is the association (natural vs connected to nuclear power), rather than the levels, or the actual size of the risk, that deems whether the thought of radiation causes an outrage. https://jmkorhonen.net/2017/02/22/hey-greenpeace-could-you-find-us-finns-a-warm-place-to-live-in/

So Fukushima may well end up the costliest accident of all time. Human errors in risk perception are the largest drawbacks to nuclear power, not only in this, but also in needless evacuations and effects on mental health, but it’s not entirely accurate to justify or gloss them over as ‘necessary’ or recommendable ways to handle a situation after a nuclear power accident. We should learn from our mistakes and do better, should we ever have a situation with such small levels of leaked radioactive contamination again. We certainly should not recommend spending vast amounts of money on undertakings that do not result in any improvements for public health. The inflated fear of radiation is an error of judgement that has already cost many dollars as well as lives.

I hope you find my answer useful.

Thanks for stopping by,

Iida/Thoughtscapism

LikeLike

Have you ever wondered about the beneficial effects nuclear power has had on the lives, wellbeing and health of people? Certainly there will be someone you know who has benefited – or even yourself:

https://bwrx-300-nuclear-uk.blogspot.com/2019/11/how-nuclear-power-in-uk-has-improved.html

And nuclear power has saved 15X more in healthcare costs than the cost of all of the nuclear power accidents. That’s money you’ve been able to spend on your own lifestyle choices, because of nuclear power:

https://prismsuk.blogspot.com/2018/01/cost-of-nuclear-power-accidents-versus.html

LikeLike

Commonly mentioned figures for the time reactor must be isolated are in the tens of millenia. As a physics undergrad in the 70s I heard this

a lot from the antinuclear crowd. When I pointed out that the nucleus was only discovered a century ago and how much we have learned since, I would then ask how likely it is that we would progress no further in the following hundreds of centuries. The answers were invariably unconvincing.

LikeLike

Pingback: Das Risiko, Risiken falsch einzuschätzen | Nuklearia

Hi. Thank you very much for this interesting post!

My major doubt about your claims was already mentioned in one of the comments above, and I’d love for you to elaborate on this. Some of the accidents you described – Chernobyl, London Smog, Benxihu – are clearly and directly related to energy generation. However, dams serve multiple purposes. My understanding – correct me if it’s wrong – is that their primary purpose is to regulate water flow, and then once you plan to build a dam, hydropower generation is a nice add-on.

What would you say to somebody who claims that these dam accidents cannot be understood as energy generation failures, and one should only consider projects built specifically for the purpose of energy production?

LikeLike

Pingback: Visiting Chernobyl, Day One, The Most Dangerous Part of the Trip: Kyiv | Thoughtscapism

Try this hydro accident in Russia. Its total deaths are not as high as those you discuss, but the immediate death toll is over twice Chernobyl’s

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/2009_Sayano-Shushenskaya_power_station_accident

LikeLike

Thanks for sharing, I had never heard of this one. 75 people killed directly, that’s tragic. And quite an environmental impact too, apparently: “The accident caused an oil spill, releasing at least 40 tonnes (39 long tons; 44 short tons) of transformer oil which spread over 80 km (50 mi) downstream of Yenisei.[16][34] The oil, which spilled during the approximately 2-3 hour cutoff of river flow when all the gates of the dam were closed, killed 400 tonnes (390 long tons; 440 short tons) of cultivated trout in two riverside fisheries, with its impact on wildlife as yet unassessed.”

LikeLike

Added some figures for the Ukraine to a blogpost regarding the health and lifestyle benefits derived from nuclear power displacing coal-fired power plants.

“…45,614 premature deaths saved…”

https://bwrx-300-nuclear-uk.blogspot.com/2019/11/how-nuclear-power-in-uk-has-improved.html

LikeLike

Pingback: Contaminated Concepts about Chernobyl | Thoughtscapism

Pingback: The Animals of Chernobyl – Trip Report, Day Three | Thoughtscapism

Pingback: The Town That Remained Despite the Chernobyl Accident | Thoughtscapism