There are a great many people who hold contrary opinions on climate change. Most of those people are not climate scientists. But there are even many climate scientists who hold contrary views to each other. Myriad blogs and news sites can help reinforce one’s view, be it that human induced climate change (or AGW – Anthropogenic Global Warming) is happening or not.

So how can we, non-climate scientists, know if climate change is happening, and if it is caused by human activities?

The natural starting point is to look for signs of scientific consensus. What are they?

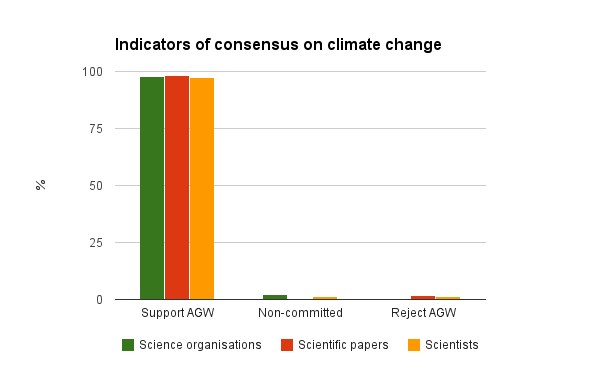

This graph gives the quick answer. It is a summary of the largest reviews of scientific publications, scientists views, and the statements of scientific organisations (here and here).

But let’s not stop there. What does that entail? There are a number of reviews and surveys. Depending on how they are set up, not all can say exactly the same thing. Furthermore, does consensus mean that scientists are voting about science?

To get a more in depth idea about the scientific consensus, let’s first take a look at:

1. Statements from scientific organisations

Wikipedia tells us the following on scientific opinion on climate change:

The scientific opinion on climate change is that the Earth’s climate system is unequivocally warming, and it is extremely likely (at least 95% probability) that humans are causing most of it through activities that increase concentrations of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, such as deforestation and burning fossil fuels.

They go on to provide synthesis reports, statements from academies of science, science councils, unions, societies, federations, and so on. They give this summary:

No scientific body of national or international standing maintains a formal opinion dissenting from any of these main points. The last national or international scientific body to drop dissent was the American Association of Petroleum Geologists,[10] which in 2007[11] updated its statement to its current non-committal position.[12] Some other organizations, primarily those focusing on geology, also hold non-committal positions.

Nasa provides another summary of the scientific consensus, with the same message:

The following page lists the nearly 200 worldwide scientific organizations that hold the position that climate change has been caused by human action.

On top of that, they also say:

Ninety-seven percent of climate scientists agree that climate-warming trends over the past century are very likely due to human activities

This is a somewhat different line of argument. It seems to be quantifying the opinions of individual scientists, not the conclusions reached by the institutions. What is this quantification of agreement among scientists based upon? Does each scientist get a vote? What do they have to be a scientist in? Do they all understand the problem in depth? Certainly there are some factors to be careful of before diminishing scientific agreement on real world phenomena into simple voting.

Asking scientists to ‘vote’ is indeed one of the ways to conduct these surveys. It does tell us something about the scientific agreement, but that’s not all consensus is about – there are more important ways of quantifying the degree of agreement.

For our second way of getting an idea about what is going on in climate science, let’s take a look at:

2. Surveys of scientific consensus

Nasa and Wikipedia mention of several surveys. From what I can differentiate, these include at least three different types.

A) Surveys of scientific publications

This means categorising hundreds or thousands of scientific papers on climate change according to positions expressed in their conclusions – if they reject or support human induced climate change. This method differs in an important way from voting. Rather it describes the scientific landscape on climate. To get published in a scientific journal, a paper must have original results to present and it must pass the scrutiny of peer-review. You don’t simply get ‘a vote’ because you are a scientist, you have to have something robust to say, too.

There are three surveys of this type what I can find:

- Powell 2013 quantifies 13,950 articles published in peer-reviewed journals, and finds that only 24 rejected Anthropogenic Global Warming (AGW). More about this study and its methodology here.

- Cook et al 2013 looks at roughly 12,000 abstracts and out of those that take position, 97% agree with AGW. In The second part of their study they asked the authors of the papers to categorise their own papers themselves. This also showed a 97% consensus. More on that here.

- Oreskes 2004 categorises more than 900 abstracts, and finds that none of them disagreed with the consensus position of human induced climate change.

Nasa mentions Powell 2013 and Oreskes 2004 in their conclusion, as well as a third survey, which is of a different type:

B) Studies with a mix of factors – scientists’ views and the relevance of their field and their body of research

There is only one study of this type that I know of, Anderegg et al 2010. They say the following about Anthropogenic Climate Change (ACC):

Here, we use an extensive dataset of 1,372 climate researchers and their publication and citation data to show that (i) 97–98% of the climate researchers most actively publishing in the field surveyed here support the tenets of ACC outlined by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, and (ii) the relative climate expertise and scientific prominence of the researchers unconvinced of ACC are substantially below that of the convinced researchers.

Then there is the third type, we could call this the democratic one:

C) Polls of scientists’ opinions

These surveys use ‘mere voting’ so to say as their methodology, and they tend to have more variability. A score of early polls conducted in the nineties have very variable rates, some majorities rejecting, some accepting AGW, depending on the wording of the questions and the subgroup of scientists asked. Among those conducted since the year 2000, I count 6 surveys of purely this type from the Wikipedia surveys page.

Most of these 6 surveys receive responses from only a few hundred scientists at a time (of the field or society of choice). The only one to go above a thousand is the survey by Doran and Kendall Zimmerman, 2009, which reached 3000 or so out of the 10 000 earth scientists polled.

Wording and rating systems differed greatly, but the overall trend is in support of predominantly human induced warming, as follows:

- 72 % (Staats 2007)

- 83.5 % (Bray and von Storch, 2008)

- 82 % (Doran and Kendall Zimmerman, 2009)

- 84 % (Farnsworth and Lichter 2011).

Two surveys stuck out of this trend:

Lefsrud and Meyer, 2012, a survey of engineers and geoscientists reported that 51% were skeptical of AGW and only 36 % ‘comply with Kyoto’, and an earlier survey by Bray and von Storch from 2003, which uses a more complex rating, seemed split roughly 50-50.

One thing that is worth considering, is that voting is indeed a crude indicator of what the body of science is agreeing on (when looking at the papers being published). Voting or scientist’s views are also not equivalent – does somebody who has published one paper have as good a grasp of the field as one who has published 15? Or someone whose topic touches on the topic of climate in a marginal way?

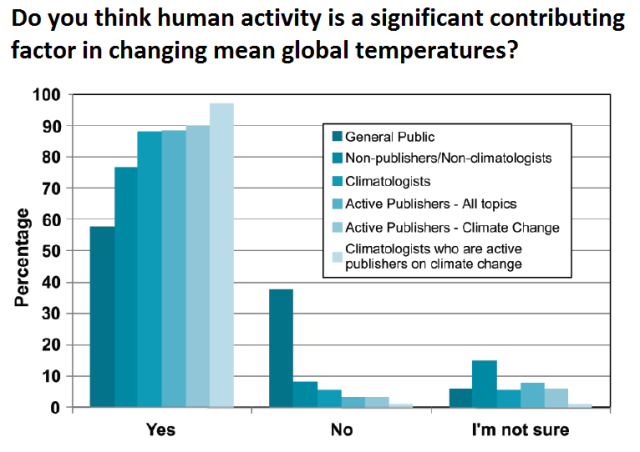

This is well illustrated by this graph which sorts the views according to their relevance, taking in consider the relation of the scientists to the active field of climate science. It also shows the difficulty that climate science has in communicating to the general public.

In the summary graph included at the beginning of this piece, the most important support for a consensus is what the landscape of scientific papers tells us. The next best indicator are the organisations’ positions. Nevertheless, scientist views can also be of interest, and to represent them I chose the datasets that incorporated an aspect of relevance in their analysis. There are two – the Doran and Zimmermann (see the graph above) and the Anderegg surveys. Incidentally, they arrive at the same degree of support among the actively publishing climate scientists (97.4% and 97-98 %, respectively).

What does all this tell us?

I understand that there is an uncertainty included in the wording of the consensus. This uncertainty, and the complexity of a topic such as global climate, probably explains why there is some room for the vocal movement of skepticism. According to the IPCC it is with 95 % certainty, or ‘extremely likely’, that global warming is mainly caused by human activities. Science as a process holds itself to such scrutiny that it can’t ever be completely sure about anything – one can only speak of different degrees of support as judged by looking at the evidence. This ‘science speak‘ may feel iffy for many people, as it always leaves room for doubt. But science should not be arrogant, because the alternative would be terrible.

Likewise, there is a clear message for me here. I should not be so arrogant as to claim that I know we should listen to a different line of reasoning than that expressed by the consensus of the ever-doubtful community of scientists. They say that the climate seems to be warming and will keep doing so if we continue emitting too much CO2.

To go against that, I should come with a whole body of new research that gives evidence of the contrary. Despite several long discussions with climate skeptics I haven’t uncovered such a body of evidence.

Any place in time is only the starting point for science, however. We shouldn’t work to polarise the debate to the point that scientists will be attacked for any criticism they make of the uncertainties of specific practical predictions of some of the climate scenarios.

Scientists will continue their attempts to uncover how exactly climate change is happening, what we can do to stop it, and what its effects on different parts of the globe, and aspects of the environment, will be. We should not make this discussion about whether AGW is happening or not, we should follow suit, and ask ourselves the interesting questions: can science tell us what the most tangible impacts will be? How should we best prepare for them? What solutions can best help us mitigate the effects?

For more on the topic of climate, you can find other pieces over at Climate and Energy. If you would like to ask a question or have a discussion in the comments below, you are very welcome, but please take note of my Commenting policy. In a nutshell:

- Be respectful.

- Back up your claims with evidence.

Well written, well researched, logically presented… and unfortunately beyond the reading comprehension level of those who could most benefit by reading it. We support a rigorous debate about these and any scientific matters. Instead, what we have is a large group of Americans treating this as a political issue, aligning themselves as cheerleaders for the side they’re on, ignoring evidence that doesn’t please them and desperately seeking scientists – or anyone with a degree – who will join with them. The result is that most of the people who are cited as “skeptics” or deniers regarding this issue are either a) on the payroll of big timber, big mining, big oil, etc., b) are an assortment of psychologists, weather forecasters, psychiatrists, etc. who really don’t understand climate issues, or c) turn out to be grinding an axe with former colleagues.

LikeLike

Thanks Barbra and Jack. I am in a process of working on different aspects of science communication, and thanks to your comment, I revisited the topic of complex vs simple messages with other people interested in science outreach, and there were some interesting resources on what works best to reach the minds of those who are opposed to the information. This was particularily inspiring: http://www.forbes.com/sites/stevemeyer/2014/06/12/persuasion-fascinating-study-shows-how-to-open-a-closed-mind/

Humans are visual animals, and I think I will do well to try to remember that including a visual representation of ones message can make a difference when words can’t. Images like simple graphs have a way of sticking with you and making you consider their message.

LikeLike

Infographics are all the rage these days. We look forward to more of your posts. Cheers!

LikeLike

Hi Iida good review. You might have been a little more critical of the methodology of some of these studies though- I have reviewed some of the critiques leveled at some of the more prominent studies here:

The kind of “consensus” you get in a social studies survey depends on the question asked- if you set the bar low enough you can get a consensus on anything!

The vast majority of so-called “skeptics” or “deniers” are well within this consensus.

The wider problem is that continual focus on this shallow consensus- which is little more than that human CO2 is exerting a warming pressure on the climate- serves to conceal what have always been the real debates, questions and uncertainties: how much warming, how dangerous, what impacts, what, if anything, can we or should we do about it.

The way this plays out in the political arena is that real policy decisions are being made now about trade-offs in the real world, about which there is no consensus at all- these are not after all scientific questions alone. Thus, on the strength of this “consensus” the US “is essentially prohibited from investing in energy projects that involve fossil fuels, a policy that may have profound consequences in places like sub-Saharan Africa that are seeking to develop oil and gas resources to help alleviate widespread energy poverty.” as discussed here:

http://www.bishop-hill.net/blog/2015/3/17/in-which-computer-models-collide-with-the-real-world.html

The shallow consensus that CO2 is a warming gas is transformed seamlessly, without democratic debate, into a scientific consensus that hypothetical deaths 50-100 years hence are more important than real, current deaths in the here and now. This is what is at the core of the heated political debate on climate, not the false-flag bogus debate about whether the world is or has warmed due to CO2.

LikeLike

Hello Graham, and thanks for your comment. I have read some of the criticism against a selection of these surveys, and a couple of good responses addressing some of the criticism in turn too. Considering the many ways one can frame a survey, there certainly are many benefits and drawbacks that can be taken into consideration. There are no reviews of the scientific landscape that would come to a decidedly different conclusion, however, because as you say as well, this is really a discussion of details. The question of human induced climate change isn’t the one under debate in the realm of scientific publications.

What comes to the heated political debate, I would point out that, sadly, policy discussion is impacted largely by what is happening in the minds of the general public, not by what the science says. Science communication is lacking – as illustrated by the second graph in the end of my piece (I added the second graph now that I had some time for finishing edits): the disconnect between the general public and the scientific views on climate change are huge. Majority of people opposed to climate action hold those positions not thanks to their expert appraisal of what adaptations would be most feasible and most necessary ones to make – but thanks to their belief that there is no AGW. Almost 40% think AGW is not happening, and another 15% are not sure what to think.

This varies by country, but the trend is worrisomely true for a large part of the globe. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Climate_change_opinion_by_country

Of course there is a lot of uncertainty in the future that climate change will bring. One of the latest set of scenarios I’ve seen is here.

http://www.newscientist.com/article/dn26243-world-on-track-for-worstcase-warming-scenario.html

There are also problems with ideological hijacking, using the threat of climate change as the reason for calling for ones’ favoured type of change in the society. I’ve even heard the term ‘solution denial’. I will continue looking to expert bodies like the IPCC and IEA for direction in climate mitigation (touched on that here, and also on the important role you mention of energy supply in alleviating poverty: https://thoughtscapism.com/2015/03/06/energy-solutions-in-a-changing-climate/ ), and hope that the more grave consequences can be avoided.

LikeLike

Thanks Iida for your reply.

This is all true but begs the question: why is such a shallow consensus that doesnt really ask the important and interesting questions made such a big deal of? Cook especially has made it quite clear that the intention was advocacy- to bring climate change center stage and push for “action.” Why? What for when the “consensus” that they have produced tells us nothing about “action” or how urgent or anything really. It is banal.

And why can’t the researchers ask more interesting questions, such as if scientists feel climate change is the biggest threat or urgent etc.. One study that has attempted this is van Storch 2009- why can this not be replicated?

So my opinion is, focusing on the consensus is a very poor mode of science communication. Consensus is only something that emerges from the data, it is not in itself how science works, so just talking about the consensus is somewhat alienating- “just believe what the scientists tell you, they all agree!” But what do they agree on? It simply isnt clear, and I think that the public to a large degree sense this. They smell a rat because they are given a mixed message- the “science” is portrayed as being this consensus, but the consensus itself is banal. So it is not very informing, and in fact drives people away.

It may not even be that people “reject the science”- more, just a big shrug. The fact is that climate change is currently progressing very slowly, has been for nearly 20 years, and is not impacting most people’s lives in any tangible way. I think this is what you are seeing in your surveys of the public who dont believe the science- it is not so much they dont believe it, bit they feel alienated from it, and they feel they are being manipulated.

And, in a very real way, they are.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Going forward our best option is to look at the problems with the best scientific data we have and which we continue to uncover. Understanding scientific consensus as the starting point for that is important. Science is the best method we have to help avoid manipulation by the media or by any one political agenda.

To quote Richard Feynman:

“Science is a way of trying not to fool yourself. The principle is that you must not fool yourself, and you are the easiest person to fool.”

IPCC is the largest and most focused organisation I know that is working on understanding climate science. Their conclusion does not ignore the uncertainties involved, neither does it aim to manipulate the public or make them jump on any ideological bandwagons, but it does acknowledge the likelihood for significant consequences as supported by the evidence we have today.

“Scientists have high confidence that global temperatures will continue to rise for decades to come, largely due to greenhouse gasses produced by human activities. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), which includes more than 1,300 scientists from the United States and other countries, forecasts a temperature rise of 2.5 to 10 degrees Fahrenheit over the next century.

According to the IPCC, the extent of climate change effects on individual regions will vary over time and with the ability of different societal and environmental systems to mitigate or adapt to change.

The IPCC predicts that increases in global mean temperature of less than 1.8 to 5.4 degrees Fahrenheit (1 to 3 degrees Celsius) above 1990 levels will produce beneficial impacts in some regions and harmful ones in others. Net annual costs will increase over time as global temperatures increase.

“Taken as a whole,” the IPCC states, “the range of published evidence indicates that the net damage costs of climate change are likely to be significant and to increase over time.”

As summarised by NASA

http://climate.nasa.gov/effects/

LikeLike

First off, there are no sources listed on your graph. I guess a preacher who’s preaching to the choir doesn’t have to give his sources. After all, it’s a choir. Secondly, if you actually weren’t a preacher, you’d talk about the cases in which scientists — and their “consensus” — were wrong, and were overturned by contrary facts. But then, who needs to do that here? It’s a choir, after all.

Nice illusion you’ve presented. Well, actually not nice at all, and not well done. But it’s a choir, after all.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hello Jake, and thanks for taking interest in my piece. Good of you to let me know that you were disappointed you could not find the sources for the graph. I should include the source links directly in the figure text too, as I understand that it’s not realistic to except that everyone will read the piece, even though I did include the links to the sources in the two-sentence paragraph just below the graph:

“This graph gives the quick answer. It is a summary of the largest reviews of scientific publications, scientists views, and the statements of scientific organisations (here and here).”

Let me paste the links here for you directly too:

Scientific papers: http://www.jamespowell.org/PieChart/piechart.html

(used the largest study, though could also have used the largest two pooled, but they have very similar results)

Scientists’ views, Doran: http://tigger.uic.edu/~pdoran/012009_Doran_final.pdf

and Anderegg: http://www.pnas.org/content/107/27/12107.abstract

Science orgs: http://opr.ca.gov/s_listoforganizations.php

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scientific_opinion_on_climate_change#Non-committal

The other significant paragraph expanding on the sources is from the end of my piece, excerpt here for your convenience:

“In the summary graph included at the beginning of this piece, the most important support for a consensus is what the landscape of scientific papers tells us. The next best indicator are the organisations’ positions. Nevertheless, scientist views can also be of interest, and to represent them I chose the datasets that incorporated an aspect of relevance in their analysis. There are two – the Doran and Zimmermann (see the graph above) and the Anderegg surveys. Incidentally, they arrive at the same degree of support among the actively publishing climate scientists (97.4% and 97-98 %, respectively).”

What comes to ‘scientific consensus has been wrong before’, there are a couple of good sources of reading for that.

Rational Wiki entry on ‘scientific consensus was wrong before’ argument:

“Primarily it misrepresents how science actually works by forcing it into a binary conception of “right” and “wrong.” To describe outdated or discredited theories as “wrong” misses a major subtlety in science: discarded theories aren’t really wrong, they just fail to explain new evidence, and more often than not the new theory to come along is almost the same as the old one but with some extensions, caveats or alternatives. Often enough, these “new” theories are already in existence and just waiting in the wings ready for new evidence to come along and differentiate them.”

“the “science was wrong before” argument conflates different types of errors within science, confusing incompleteness of theories with being outright wrong. This, as Isaac Asimov called it in his essay The Relativity of Wrong,[2] is a form of being wronger than wrong.”

http://rationalwiki.org/wiki/Science_was_wrong_before

Also connected to something I wrote on science:

“It all really boils down to: Why science? Aren’t there other just as important sources? What makes science so infallible? I’ve often heard the counter-argument that science doesn’t know everything. So why should we listen to it?

The answers are: science is not infallible. It doesn’t know everything. But it’s the only one in the game. There is no competing system of knowledge. Science is the common denominator for all those endeavours that openly admit that ‘we think that this might be the case but we will test real hard to see if it turns out really to be so’. If you are looking for knowledge about the world, science is the one gig in town that’s sitting down around the table and thinking hard on ‘how can we truly know something?’

Here is a great take summary of the scientific method

The Method of Science or Reflective Inquiry:

The other methods discussed are all inflexible, that is, none of them can admit that it will lead us into error. Hence none of them can make provision for correcting its own results. What is called scientific method differs radically from these by encouraging and developing the utmost possible doubt, so that what is left after such doubt is always supported by the best available evidence. As new evidence of new doubts arise it is the essence of scientific method to incorporate them – to make them an integral part of the body of knowledge so far attained. Its method, then, makes science progressive because it is never too certain about its results.”

And I really like the graphic representations of this in this Quora answer: http://qr.ae/0WO2L

Thanks for stopping by!

Iida

LikeLiked by 2 people

Pingback: Genetically Engineering Foods Involves Greater Precision and Lower Risk of Unintentional Changes Than Traditional Breeding Methods – The Credible Hulk