The first in my series of 17 Questions About Glyphosate is the one topic made famous by a somewhat confusing classification system of potential cancer hazards.

The first in my series of 17 Questions About Glyphosate is the one topic made famous by a somewhat confusing classification system of potential cancer hazards.

Much media and public attention on glyphosate followed after World Health Organisation subgroup, International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) declared that according to their classification, glyphosate falls under substances 2a – “probably carcinogenic”. What the media attention often failed to report is that IARC does not actually look at risk – how big is the risk for said carcinogenic effects? What levels are safe and what aren’t?

Instead it aims to classify a kind of absolute possibility as a hazard: would the exposure to agent x be carcinogenic in any possible scenario, dosage, length of exposure? Its classification of glyphosate to a “probable carcinogen” has been under some criticism, considering that IARC excluded much of the existing reputable evidence on the topic, that the IARC made connections to human effects where certain study authors themselves did not agree, and also for non-declared political conflict of interest within the IARC, and the way these actors have used the classification for political lobbying (for more, see The Shady Politics Of The IARC Glyphosate Hazard Assessment – the site is down for the moment, meanwhile there’s also a GLP aggregate page for it).

But even if we set these questions about the validity of the assessment aside, and simply assume it to be accurate, what does classification as a 2a substance mean? The scale IARC uses includes the following groups:

- 1) definitely carcinogenic

- 2a) and 2b), probably and possibly carcinogenic

- 3) not classifiable, and

- 4) probably not carcinogenic.

Bloomberg has a very user-friendly graphic in their article on red meat as a carcinogen, where they give an overview of a multitude of substances (and other exposures, such as occupations) classified within the IARC system. You can find a screenshot of their great interactive graphic below, with processed meat featured from group 1, and red meat from group 2A (in the same class as glyphosate). They write:

It’s important to note that the agents at the top aren’t necessarily the most dangerous. They’re the ones with the clearest evidence of hazard. WHO seeks to identify carcinogens “even when risks are very low at the current exposure levels, because new uses or unforeseen exposures could engender risks that are significantly higher,” the agency says. In other words, even though WHO has determined that red meat is a carcinogen, the report doesn’t quantify how much meat it would take to cross into the danger zone.

Bloomberg’s article and interactive graphic is definitely worth taking a look at. Just a screenshot sample pictured here.

So far out of all the near thousand substances evaluated, IARC has named only one ‘probably not’ a carcinogen. Of course, most of the substances studied are chosen because an idea that they may under certain circumstances cause cancer. IARC does provide potentially useful information, just not the kind which a typical consumer might think of when they read the headlines. IARC provides no insight about which kind of exposure would be significant for our day-to-day lives. IARC is not really a valuable consumer information service – after the media attention given to IARC’s classifications, Ed Yong over at the Atlantic went as far as to call for “a separate classification scheme for scientific organizations that are “confusogenic to humans.” To steer ourselves further away from the confusion, let’s remember that exposure and dose remain the crucial questions when it comes to making good health choices.

There are several scientific review papers (collected here on this excellent resource wiki of the Food and Farm Discussion Lab) that have looked at real world data of glyphosate exposures and their connection to health effects. Four of these review articles look specifically at cancer and genotoxicity, and they all conclude that there is no connection between glyphosate and cancer incidence.

So why did IARC classify it as a probable carcinogen? To make things less confusogenic, there is a very illuminating blog post from weed ecology professor Andrew Kniss, over at WeedControlFreaks blog, on the studies IARC used in their monograph: Glyphosate and cancer what does the data say? Andrew Kniss provides a very useful graphic to help us make sense of the evidence landscape:

See the excellent blog post, Glyphosate and cancer – what does the data say? Over at WeedControlFreaks.

If you are interested in the spike of Non-Hodgkins Lymphoma, it good to start with mentioning that those were case-control studies, where the number of people actually exposed to glyphosate were very small – tens, not hundreds, and even within the population of cancer sufferers, only a few percent had glyphosate exposure, as Andrew Kniss lays out in his piece. This means that the evidence is far from conclusive. Now, let’s compare Andrew Kniss’ graphic to this one from another great piece in Vox, This is why you shouldn’t believe that exciting new medical study:

From This is why you shouldn’t believe that exciting new medical study, based on Schoenfeld and Ioannidis paper in American Journal of Clinical Nutrition.

One way to sum it up: cancer – it’s not that simple. Evidence that seems to support or reject a hypothesis may still be wrought with complexities that eludes simple interpretation. It is no wonder if it’s difficult for lay people to try to put all the data from scientific studies into proper context and perspective. The Farmer’s Daughter helps with the effort by comparing the classification to that of other known definite or probable carcinogens: very hot beverages, wood dust, and shift work for instance, which also fall under class 2A, are all things we can more intuitively assess (it’s better not to eat all too much meat, or breath in wood dust, or get yourself too exhausted with shift work, especially if it doesn’t suit you). She writes:

The following things have also been included in the 2A classification: manufacturing glass, burning wood, emissions from high temperature frying, and work exposure as a hairdresser.

But what’s even more revealing are the things that have been classified in Group 1, things that do cause cancer: drinking alcohol, formaldehyde, radon, solar radiation, wood dust, and estrogen. So these are things that will cause cancer, while glyphosate (according to IARC) might cause cancer.

So, if glyphosate could cause cancer, does it? According to several reliable sources, no.

An actual risk assessment on glyphosate by the WHO and the United Nations Food and Agricultural Organisation (FAO) finds no reason to think glyphosate in the amounts found in our food or through normal occupational exposure would be carcinogenic to humans.

Evaluations by Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in US and European Food Safety Authority (EFSA, report here), as well as the German Federal Institute for Risk Assessment (BfR statement here, and their evaluation in English here) have also reached the same conclusion. The WHO statement as reported by Reuters:

“In view of the absence of carcinogenic potential in rodents at human-relevant doses and the absence of genotoxicity by the oral route in mammals, and considering the epidemiological evidence from occupational exposures, the meeting concluded that glyphosate is unlikely to pose a carcinogenic risk to humans from exposure through the diet,” the committee said.

If you would like to watch a video on the topic, this civil and informative discussion where two scientists are interviewed in a Canadian News show does a good job of neatly clarifying many of the important aspects in just 15 minutes. They illustrate he difference between a ‘hazard’ and a ‘health risk’ by likening the risk of glyphosate to the consumer to a visit at the zoo. Is the bear in the zoo a risk to your health? In the right (well, wrong) context, yes. But should you be afraid to visit the zoo? No. For more on hazard and risk, see the series I’ve written on risk with neuroscientist Alison Bernstein, Risk In Perspective: Hazard and Risk Are Critically Different Things.

A 2013 review on glyphosate and glyphosate formulations deems neither to be genotoxic under normal human or environmental concentrations. The most recent review on glyphosate and cancer from 2015 concludes:

The lack of a plausible mechanism, along with published epidemiology studies, which fail to demonstrate clear, statistically significant, unbiased and non-confounded associations between glyphosate and cancer of any single etiology, and a compelling weight of evidence, support the conclusion that glyphosate does not present concern with respect to carcinogenic potential in humans.

UPDATES: More research

Recent European Chemicals Agency review on glyphosate has also concluded that Glyphosate is not classified as a carcinogen:

Glyphosate not classified as a carcinogen by ECHA

ECHA’s Committee for Risk Assessment (RAC) agrees to maintain the current harmonised classification of glyphosate as a substance causing serious eye damage and being toxic to aquatic life with long-lasting effects. RAC concluded that the available scientific evidence did not meet the criteria to classify glyphosate as a carcinogen, as a mutagen or as toxic for reproduction.

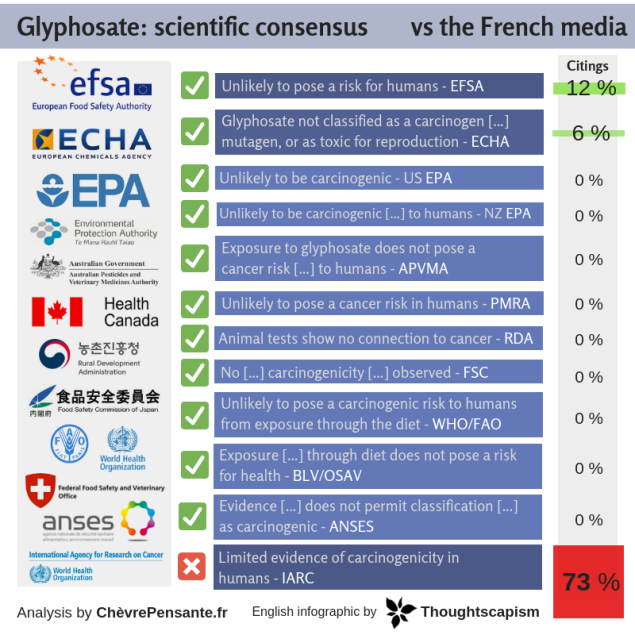

While the agreement on glyphosate and cancer is very robust among scientific organisations, sadly the media often does not reflect that. See the french media blogger Chèvre Pensante’s analysis contrasted with the positions of scientific organisations below:

In November 2017, a study in the Journal of National Cancer Institute, following 54,000 agricultural workers over a period of two decades, found that “glyphosate was not statistically significantly associated with cancer at any site.”

In the light of recent reviews, I have also written an complementary piece titled IARC Under Fire from Scientists: Mission Outdated, Methods Lacking, in short:

- Cancer classification on hazard-identification such as IARC and UN GHS are outmoded.

- Chemicals with differences in potency and modes of action placed in same category.

- Unintended consequences: health scares, costs, and diversion of public funds.

- Modern approaches based on hazard and risk characterization should be used.

- International initiative needed a consensus on for carcinogenicity.

I hope the health authorities over the globe will get the message and form a clearly communicated consensus based on up to date scientific methodology that does not have the side-effect of creating needless scare campaigns.

For more about glyphosate health claims, please see questions 2.-3. Glyphosate and Health Effects A-Z.

Please see the parent post, 17 Questions About Glyphosate, for more information on connected topics. If you are interested in other environmental or health topics, you can find my other pieces and further resources under Farming and GMOs, The Environment, and Vaccines and Health. If you would like to have a discussion in the comments below, please take note of my Commenting policy. In a nutshell:

- Be respectful.

- Back up your claims with evidence.

Pingback: IARC Under Fire from Scientists: Mission Outdated, Methods Lacking | Thoughtscapism

Pingback: 1 of 17 – Does Glyphosate Cause Cancer? – GMO Building Blocks

Pingback: Roundup (glyphosate), Cancer and the Courts - What Does It All Mean - Garden Myths