Economy: an intricate system of mediums of exchange that enables many complex workings of our societies. It’s a wondrous interconnected network of symbols, really, a true testament to human ability of abstract thought.

How we should best steer or influence the economy is a vast arena for political debate. But even before we sit down for that political discussion, we should bring a few fundamental insights about the role and workings of the economic system to the table.

One thing is certain: any major change of our societies should take into account its impacts on the economy. Another thing is certain too: if we allow climate change to continue past several degrees in the near future, the effects will be so grave that many concrete fundaments of a working economy, things like resource availability and organised networks of laws and societies that coordinate their exchange, are set to change dramatically. There will also be a great deal of suffering, death, and major blows to many of the natural ecosystems as we know them, along the way.

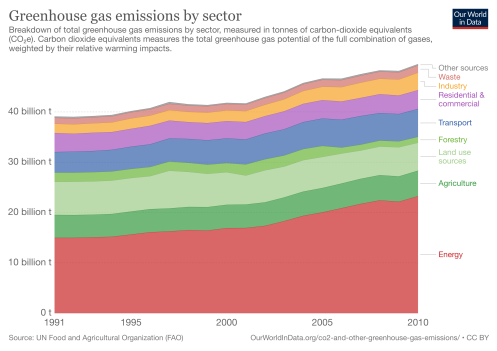

Our World In Data: Global greenhouse gas emissions by sector.

If we like things such as human wellbeing, the natural world, as well as organised societies and economies, we should try to find ways of making the economy work toward the goal of sustaining all these things in the future. That means urgently finding efficient economical paths to decarbonisation. This means tackling concepts like externalities, system costs, and ‘discount rates.’

The largest human source of greenhouse gasses by far is the energy sector. Electricity, heating, and fuels for transport account for more than half of greenhouse gas emissions – this is why a person like me, a biologist and environmentalist, has started reading and writing so much about energy.

The economy of emissions – it pays to externalise

There are many issues where economic evaluations fall short on decarbonisation goals. One of the largest is that so many of the true and debilitating costs of energy are externalised onto the society at large – that fossil fuels get to make a profit while the societies at large pay the costs of their emissions, through millions of loss of lives directly, every year, and changing of the climate in the long run. Fossils appear cheap, because our wondrous symbolic systems of value have made a terrible oversight concerning their true price. We should fix that.

Thousands of economists agree – they argue in favour of a carbon fee and dividend in The Largest Public Statement of Economists in History. It’s a simple system that will put a price on emissions, then pay it back to the public, allowing people to save money by making low-carbon choices. Borrowing a quote from the piece Bipartisan group of economists calls for carbon tax:

“this is not controversial […] the economics is really simple.”

It’s a first crucial step toward a fair economic system that does not freeload on the health and wellbeing of current and future generations’. But there’s more.

The economy of decarbonised grids

Even when we turn our attention to the economy of the alternatives, of low-carbon sources of energy, economic evaluations often mislead us from the real objectives. One of the common ways they do this is by ignoring that the goal is a working decarbonised grid. Economics of decarbonisation is about more than the current price of one particular installed unit.

This can be remedied by looking not only at the costs of separate parts of the energy sources on the grid (say with LCOE, levelized cost of energy), but by estimating the costs that go into an entire system maintaining a constant, reliable electricity delivery to the society at large.

This includes not only power plants but transmission lines, backups, batteries etc, looking at when and how much energy can be produced – the costs that go into the entire network.

The costs of getting to decarbonised grids was addressed well in a recent MIT report, which I wrote about earlier, and they clearly showed that Nuclear Power Is a Crucial Piece of the Carbon-Free Puzzle.

But there’s yet another concept insidiously baked into economic estimates, which easily distorts us from the objective – the best methods for rapid, scalable, and sustained decarbonisation.

I’m talking about something called ‘discounting.’

Will clean energy have value for our children and grandchildren? AKA ‘Discounting’

Calculating with a discount rate is a way for investors to figure out how they can quickly win back their money from their investment. In practice, by using a discount rate, we are estimating future profits to get ever smaller in value to us as time passes. In a hurry to make a profit? Use a higher discount rate to highlight investments with swiftest returns.

Graph adapted with permission from a Finnish article by physicist Jani-Petri Martikainen (article in Finnish, title translation goes along the lines of:) So you care about future generations. How does that show?

Even climate-focused institutions like the IPCC give out reports that use ‘discount rates’ as high as 10% (strikingly going against their own previous discounting recommendations). This has a dramatically devaluating impact on any investments that could benefit us just ten or more years down the line. The choice of such high discount rates should not silently be baked in the estimates, but rather lifted up for scrutiny for what it is: disregard of long-term action.

IPCC’s discounting practices were discussed in more detail in by physicist and blogger Jani-Petri Martikainen in Discounting and costs (Part 2): IPCC WGIII report on mitigation:

[…] the IPCC in Chapter 3 suggests a discount rate in the range of 2-6%. What discount rate is used in chapter 7 to compare levelized cost of energy (LCOE) for different energy sources? That would be 10%! Authors of WGIII decided not only to use a very high discount rate, but also not to give their results at different discount rates so that the effects of this assumption could be observed. Considering that authors of Chapter 3 specifically emphasized how crucial this issue is in evaluating mitigation policies, the approach in Chapter 7 seems indefensible.

I decided to illustrate the effects of discount rates visually (see below). I chose similar, medium to high discount rates of 5-10%, a range also used by the IPCC. At the 10% rate used in their report 2014, low-carbon energy produced in 30 years from now would be worth but 4% of its value today; only 1% after 40 years; and 0.1% at 60 year mark – the common life-time of a nuclear plant (with potential to prolong up to a century). That’s hardly more than a rounding error in comparison to the only ‘really valuable’ first few years of energy production.

In other words, with high discount rates, it pays not to be built to last.

Illustration of value deflation at discount rates of approximately 5-10%, used by IPCC. For a table of discount rate values over time, see Partanen on Nuclear Cost for Dummies, and Future Generations

If IPCC chose instead a rate at the lower end of their own recommendations, a 2% discount rate, then low-carbon energy produced in 35 years from now would at least be viewed as retaining about half of its value, and less than 30% of it after 60 years.

It is in fact mind-boggling that the value of an environmental investment should be considered worthless in a few decades. For me, the knowledge that we can make decisions today that will provide my future grandchildren with vast amounts of low-carbon energy, are among the most important aspects about investing in nuclear power.

While the existence of various ‘short return of investment’ -dynamics is important for the smooth workings of the economic system, especially for actors with only little resources at their disposal (not to lock their scarce resources into something that will profit them only slowly over a longer time), when applied too generally, the practice helps cement one of the least admirable qualities of economics, and indeed, humanity: our focus on short term gain even when it means disregarding actions necessary for our long-term wellbeing.

Survival of the wisest

It all comes back to the point that economic systems should, quite self-servingly, be steered in a thoughtful manner concerning things like the role of freeloaders and choice of discount rates. Harnessing our economies to help with quick and sustained action on climate change is a matter of self-preservation. Put in terms of economic research, in MIT Review of Economics and Statistics, the dangerous uncertainty of the future can’t be ignored in economic policies:

the economic consequences of fat-tailed structural uncertainty (along with unsureness about high-temperature damages) can readily outweigh the effects of discounting in climate-change policy analysis.

Energy analyst Rauli Partanen re-iterates many of these concepts in a very approachable fashion in his article Cost of Nuclear for Dummies , and Future Generations. To borrow his words:

We are supposed to be leaving the earth a better place for our descendants. Discounting is one of the economic mechanisms that can make this practically impossible.

Most people also don’t recognize that we are doing discounting (or they might not understand the principle) because the chosen rate for a particular report or scenario, and the reasoning behind it, is almost never presented clearly or discussed openly. As a society, we should recognize that discounting at higher rates leads us to prefer consuming more fossil fuels today instead of building nuclear, wind, or solar. Fossil fuels give us immediate benefits (profits) and leave problems (costs) for the future, where they don’t seemingly matter anymore.

Although we may often be short-sighted, human ability for abstract thought is nevertheless formidable. Economic systems today are a testament to our ability to handle symbolic tokens of value in intricate societal networks. But we shouldn’t sell next generations short on our abstract human marketplace. Instead, we should view this as a challenge: how to evolve our financial systems so that they may help us safeguard and self-regulate, not only for our benefit, but for our children’s as well.

If our economies are to survive, they need to allow for vital long-term investments. They must become sustain-economies.

For more of my articles on climate and energy, look here. I also recommend the short, evidence-dense book Climate Gamble and the graphs available in their blog. If you would like to have a discussion in the comments below, please take note of my Commenting policy. In a nutshell:

- Be respectful.

- Back up your claims with evidence.

Iida, I appreciate the analysis of discount rates, but consider that nuclear power plants can have very long lives. The one in Florida is being extended to 80 years. Its value to future customers persists, undiscounted.

The money to build a nuclear power plant can be a investment, but the investor sees two components: 1) the cost of money, which you describe, and 2) the risk of loss, which can be from some technical error or a political/regulatory blow. Examples would be improperly cutting a hole in the containment dome to replace equipment, or shutting down all nuclear power plants because one failed.

Best is to lower the capital cost required to be invested. Your low-cost scenario results in 5 cents/kWh; our ThorCon design of $1.2/watt leads to 3 cents/kWh, coming out of the plant, before government taxes, fees, licenses, etc.

LikeLike

In many comments I’ve made on facebook and elsewhere, I’ve mentioned the beneficial effects of nuclear power on a nation’s health and wellbeing. I suspected the ‘health/body-count’ would be high enough to state that those effects would apply to ‘someone you know’.

Well now I’ve done some figures for the UK and they are impressive – at least, they impressed me.

Might I suggest other pro-nukers do the same for their country and use this ‘someone you know’ counter, particularly against the radiophobes wanting to ban nuclear on the grounds of the terrible effects that nuclear waste might have on health and wellbeing:

https://bwrx-300-nuclear-uk.blogspot.com/2019/11/how-nuclear-power-in-uk-has-improved.html

LikeLike

Thank you for demonstrating how critical thought is used in Science. Far too many of us treat scientific institutions as oracles — submit a question, receive a definitive answer. We are much less comfortable with what Science actually is, a framework and process by which to manage uncertainty. It is an ongoing process that converges on the best possible understanding. It relies on challenges as well as independent confirmation. It is not a vending machine.

Thank you for doing your part!

LikeLike