I finally found time to write about my visit to Chernobyl. I hope to do justice to the tremendous impression left by the people I got to meet, including locals living in the area, former clean-up workers, as well as scientists currently working in the Exclusion Zone. First up: arrival in Kyiv.

I finally found time to write about my visit to Chernobyl. I hope to do justice to the tremendous impression left by the people I got to meet, including locals living in the area, former clean-up workers, as well as scientists currently working in the Exclusion Zone. First up: arrival in Kyiv.

The first thing I noticed about Ukraine were the fires. As my airplane descended toward Kiev in the east, I saw three large pillars of smoke rising from the countryside underneath. I can’t be entirely certain as to their causes. I arrived during an early-autumn heat-wave, and the fires could have been accidental. But the Ukrainian conservationists I talked to later told me that there was a widespread problem with burning fields to get rid of stubble or similarly ‘cleaning public areas’ of leaves or other plant matter. Driving across the countryside the next day, we again witnessed a large stubble field burning.

Farmer burning stubble on a field near the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone

But I’m getting ahead of myself – on day one, I met up with documentary film-maker Frankie Fenton (Kennedy films) and his crew at Boryspil airport. After a half an hour of calls back and forth and wandering across the parking-lot, we finally located our driver. He showed us to his old German cleaning van repurposed as a minibus, still proudly advertising “Reinigungsgeräte” and “Gabelstapler” on all sides.  We packed ourselves into the van and headed through the congested traffic to our hotel in the center of Kyiv. I could hardly contain my excitement, because we were about to meet up with some big time environmental scientists:

We packed ourselves into the van and headed through the congested traffic to our hotel in the center of Kyiv. I could hardly contain my excitement, because we were about to meet up with some big time environmental scientists:

- Jim Smith, a physicist working in the area since the 1990s, who literally written the book on the effects of the accident;

- Mike Wood, a biologist conducting award-winning research on Chernobyl wild-life (the TREE project);

- and Gennady Laptev, who actually worked as a Chernobyl liquidator for three years, responsible for helicopter dosimeter surveys around the plant after the accident. Nowadays he is the head of the Radiometric Laboratory in Ukraine.

There was no lack of interesting discussion topics! Gennady, Mike, and Jim took us to a nearby Ukrainian granny-style restaurant where we sketched out our plans for our visit to the Chernobyl zone. First we’d travel to Narodychi, a town some 10,000 strong, still stubbornly located in the “zone of obligatory resettlement.” The scientists were meeting with the town administration, and we would also visit and see some of the local life in the town’s kindergarten. By evening we’d aim to be at the Exclusion Zone, go through the check-point, and head over to our hotel in Chernobyl town. Next morning in Kyiv I woke up early, plagued by a particularly persistent cough. I admired a breathtaking sunrise over the city from my hotel balcony while waiting for the first opportunity for tea. The declaration of ‘room service 24/7’ and ‘breakfast at 7’ had little meaning in the context of eastern European service mentality – in practice it was an unyielding ‘earliest at 7:30.’ The lone waiter finally had mercy on me at 7:20, after I’d been coughing miserably at my empty table.

There was no lack of interesting discussion topics! Gennady, Mike, and Jim took us to a nearby Ukrainian granny-style restaurant where we sketched out our plans for our visit to the Chernobyl zone. First we’d travel to Narodychi, a town some 10,000 strong, still stubbornly located in the “zone of obligatory resettlement.” The scientists were meeting with the town administration, and we would also visit and see some of the local life in the town’s kindergarten. By evening we’d aim to be at the Exclusion Zone, go through the check-point, and head over to our hotel in Chernobyl town. Next morning in Kyiv I woke up early, plagued by a particularly persistent cough. I admired a breathtaking sunrise over the city from my hotel balcony while waiting for the first opportunity for tea. The declaration of ‘room service 24/7’ and ‘breakfast at 7’ had little meaning in the context of eastern European service mentality – in practice it was an unyielding ‘earliest at 7:30.’ The lone waiter finally had mercy on me at 7:20, after I’d been coughing miserably at my empty table.

Kyiv sunrise from my hotel balcony

I begun to wonder if the fog, which so poetically enveloped the cityscape, wasn’t a sign of a more worrisome problem. A heat-wave with stagnant air pooling over the city? Check. Congested traffic with a large percentage of old cars, check. Culture of illegal clearing of plant matter with fires, check. Heavy industrial areas a few hours south of Kyiv, check. I decided to try to find out. I discovered a warning from earlier in the summer from the State of Emergency, declaring nitrogen dioxide levels at five times the norm (NO2 is a pollutant from traffic and fossil fuels). I also found out that Ukraine has one of the highest mortality rates from air pollution in Europe, ranking fourth in WHO statistics, after Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, and Albania.

View over the Dnieper River running through the center of Kyiv.

Although I couldn’t find current local data on air quality (in English), it wasn’t completely unreasonable to suspect that my aggravated cough and the heavy fog could have been side-effects of air pollution. The sun burned through the fog soon, in any case, and we had another windless 30-degree (88 F) day on our hands. Before we set out in our cleaning van, our cameraman went out for a smoke, then came back and struck up a discussion about what kind of risks the visit to the Exclusion Zone would entail. His concern is perfectly understandable. It’s the kind of thing that any sensible person visiting Chernobyl would want to know. Frankie, being a good boss, had underlined that he would take the matter of his crew’s safety very seriously, and made sure to have appropriate protections like gloves and breathing masks at hand. My husband, too, had expressed being nervous about me going – and bought me a pack of hazmat suits.

The crossing next to our hotel didn’t have traffic lights, only one traffic police. The concept of lanes was relative.

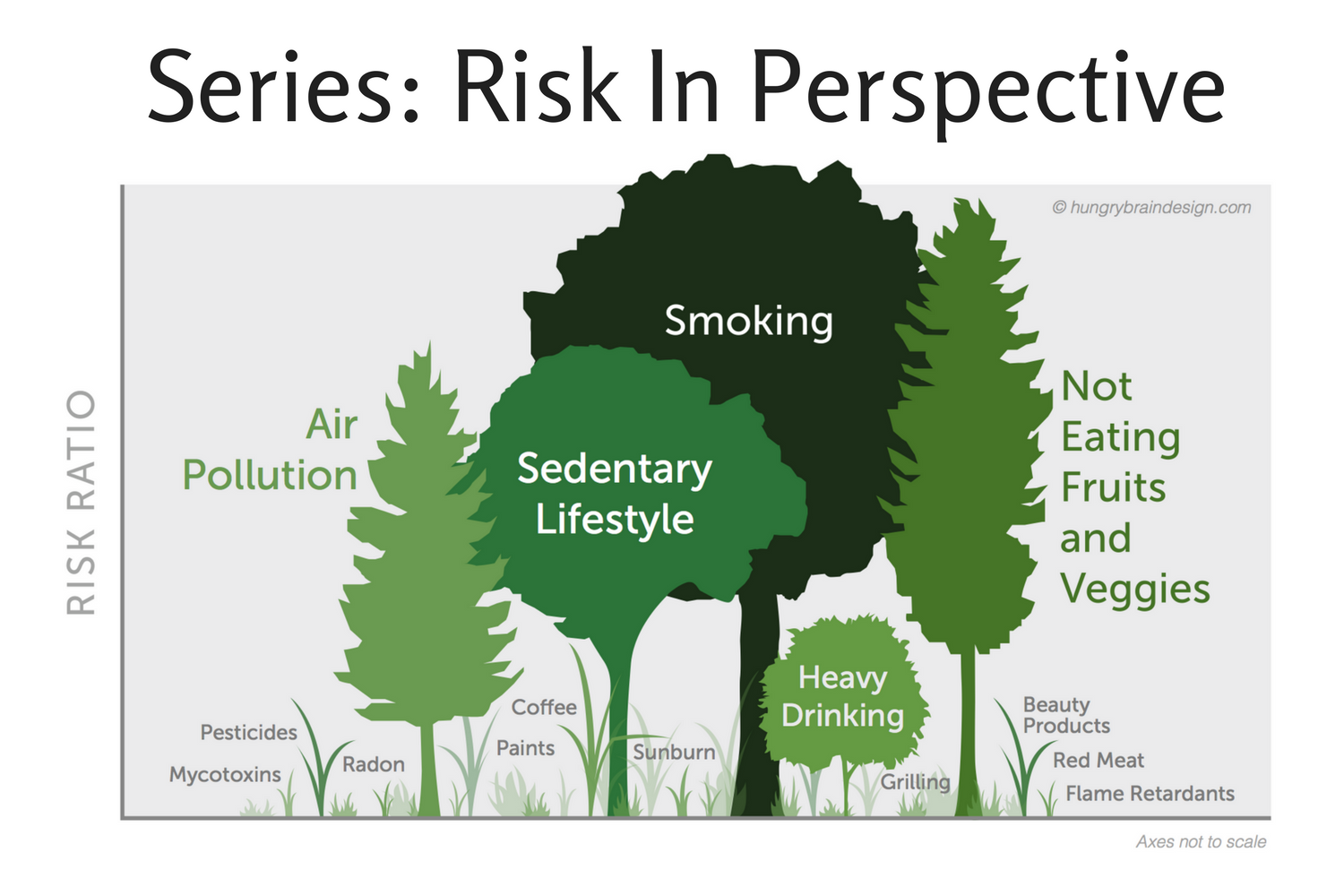

But looking at a pack of cigarettes in the camera-man’s hand, having the constant cacophony of the chaotic multi-lane traffic in the crossing behind us, waiting for us to dive into it… I didn’t even know where to start. I didn’t want to be blunt or inconsiderate. But nevertheless, I have to call a spade a spade, so let’s start here: CDC estimates that smoking increases risk of death by about a 3-fold (ie, by 300%). It’s one of the leading causes of death in the world according to the WHO, with estimates that it kills up to half of smokers. Tobacco has been indicated as a cause of as many as 20% of all deaths in developed countries. Next up, we were just about to embark on a long drive. Being in Ukrainian traffic probably increases our risks of accident by about two or three-fold compared to our home countries (although accidents like falls and drownings still claim more lives, even in Ukraine, and we are by no means immune to such risks during our trip either).

Hotel Salute, Kyiv, central Pecherskyi District. Photo wikimedia, Tiia Monto, CC 3.0.

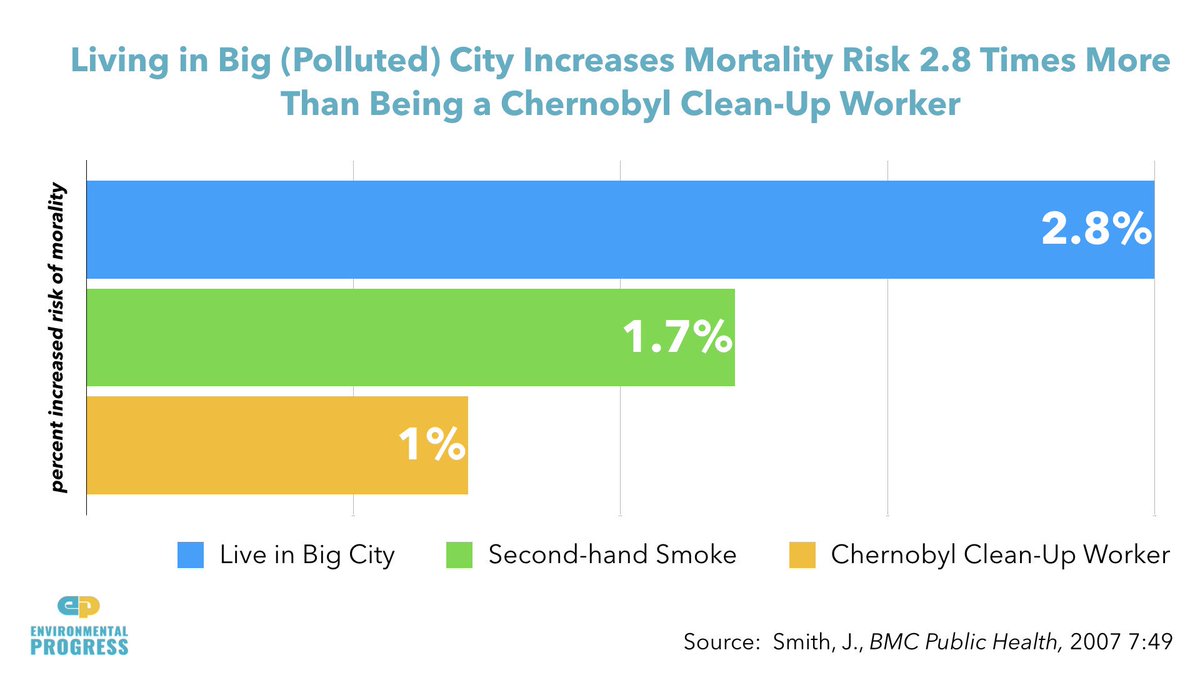

Coming from a place with good air quality, long-term exposure to levels of average Ukrainian air pollution (16.9 ug/m3 PM2.5) would increase all-cause mortality by more than 6% (WHO estimate). Short-term exposure to air pollution might not sound like a very dangerous thing, but even a few days at the average Kyiv levels is associated with around a 0.5-1% increase in daily mortality rates (more on that in a fresh study in the New England Journal of Medicine). That’s still a smaller risk than regular exposure to second-hand cigarette smoke. (Ukraine, btw, is in the top ten tobacco-smoking countries in Europe.) Meanwhile, in Chernobyl? To date, there have been on the order of 200 confirmed deaths caused by radiation from the Chernobyl accident, 30 right away, and about 160 in the decades after – that’s on average about seven deaths per year. The WHO’s theoretical estimate of the maximum number of deaths in Ukraine, although they cannot actually be confirmed from the data (hence the ‘theoretical’ part), are a few thousand total. That would be on the order of 50-100 per year. In contrast, almost 60,000 people die from air pollution in Ukraine every year. Even Chernobyl liquidators, like Gennady – people who worked to help clean the acute leakage of radiation around the plant – have had but a 0.4-1% increase in their all-cause-mortality. So, unless you were a Chernobyl clean-up worker… your risk from being in Chernobyl is not likely to come close to the risks of even spending a few days in big city with less-than-optimal air quality.

Pictured is the risk for the high-exposure group of Chernobyl liquidators (250 mSv) – low exposure group (100 mSv) had a 0.4% increase in risk. For more, see the study (authored by our travel companion Jim Smith).

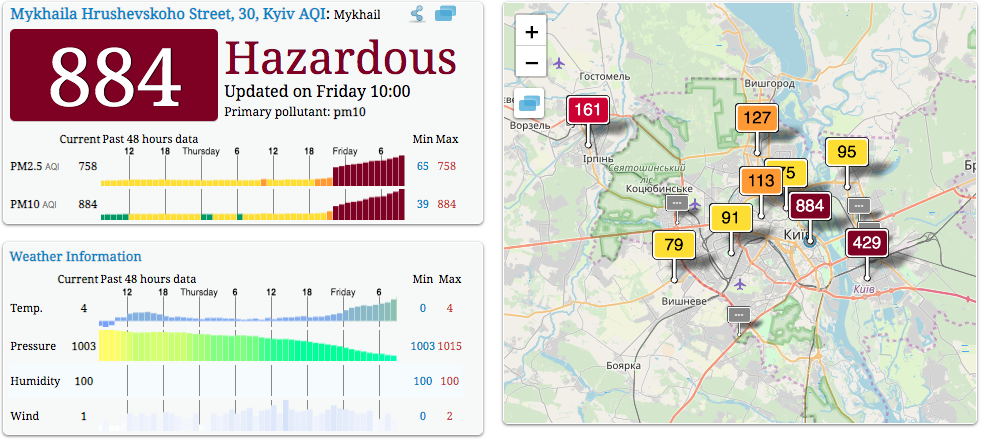

Visiting Kyiv could be considered downright hazardous if you come during a bad time. In addition to the warnings given in the summer, a worrisome spike of air pollution was reported again a month after our visit. The smog forced Boryspil airport to make a halt in flights on October 21st. They measured particulate levels at 196 PM2.5 – 196 micrograms of particulate matter smaller than 2.5 micrometers in size, found in one cubic meter of air. These are the smallest and most dangerous kinds of particles, because they can enter deep into our respiratory system. A few days with such levels could entail more than 10-fold increase in daily mortality rates (though the increase tapers off somewhat at higher concentrations). They are higher even than PM2.5 averages in the ten most polluted cities in the world (in India, Pakistan, and China, ranging from 110 to 140). I discovered another troubling spike right as I was writing this – a whopping high of 758 PM2.5 (with PM10 particles at 884 ug/m3, see screenshot below) according to The World Air Quality Index. I could hardly believe my eyes – and this measurement station is only a ten minute walk down the street our hotel was on.

Kyiv had severely poor air quality on 29th of November according to The World Air Quality Index.

The spike carried on to the next day, with PM2.5 maximum at 778. While only two stations reported “hazardous” levels, another two showed levels over 100, described “unhealthy for sensitive groups,” and one with reading above 150, simply “unhealthy.” On Monday, the situation returned to a more normal spread (15-100).

Air pollution is no small risk. The Great London Smog 1952, worst air pollution disaster in the world killed 12,000, and currently 7 million people per year die from air pollution. More in World’s Deadliest Energy Accidents ion Perspective.

I’ve found no explanation or news about the situation, which The World Air Quality Index says is based on data from the Central Geophysical Observatory of Ukraine. If these readings were accurate, the pollution levels were serious. Similar were reported in Delhi during their worst smog in 17-years in 2016, and in Beijing during a record-high called ‘the blackest day’ in 2013. After two days of >700 PM2.5 levels, we could expect more than a 40-fold increase in daily deaths. That’s seriously risky. But to bring us back to the topic at hand…

Is it risky to visit Chernobyl?

How could I try to give an appropriate answer someone sincerely asking about the risks of visiting Chernobyl? How to explain that all the caution, the check-points, the tight regulations around the Exclusion Zone, are there because we instinctively feel nervous about radiation? So for this one particular type of hazard, we have decided to limit our exposure to extremely low levels. Whereas much greater risks in our environment are treated as mundane. No check-points protect us from the largest risks of our journey, like air pollution, road injuries, falls, alcohol, cigarettes, or infectious disease. The breathing masks and gloves which we brought would benefit our health much more if worn while going through airport security checks, say, or walking amidst the thick traffic of central Kyiv. The hazmat suits (that my husband so kindly bought for me) I left at home. The long-sleeve shirts and trousers, dictated by the Chernobyl rules, would protect us nicely from the UV-radiation of the blazing sun.

Cryptic declaration over the tap in the bathroom.

Ahead of our car ride to the Zone, I was a little apprehensive about the prospect of bad roads, Ukrainian driving, or potential permit complications with the officials (and possibly the quality of drinking water – see photo 😉 ) – but not our stay in Chernobyl. I had read enough to know that even the most contaminated parts of the Zone were not dangerous to visit. For any statistically detectable (population level!) effects we’d practically have to eat or inhale a dustbath from a rare hotspot or become permanent residents right on top of one. “You don’t have to worry,” I told our camera-man and smiled, feeling helpless over how difficult it is to convey how misplaced our intuitive fears can be. “It’s more dangerous in Kyiv than it is Chernobyl.”

Next up: The town that Remained Despite the Chernobyl Accident. Whole series:

- Visiting Chernobyl, Day One, The Most Dangerous Part of the Trip: Kyiv

- The Town That Remained Despite the Chernobyl Accident

- The Animals of Chernobyl – Trip Report, Day Three

- Contaminated Concepts about Chernobyl

For further articles on Chernobyl, you can read my pieces: “What About Chernobyl?” World’s Deadliest Energy Accidents in Perspecive and “What About Radioactive Wastelands?” A Look at Chernobyl’s Effects on Nature, or on radiation: Radiation and Cancer Risk – What Do We Know? and Radiation Exposures at a Glance. If you would like to have a discussion in the comments below, please take note of my Commenting policy. In a nutshell:

- Be respectful.

- Back up your claims with evidence.

Pingback: The Town That Remained Despite the Chernobyl Accident | Thoughtscapism

Pingback: Contaminated Concepts about Chernobyl | Thoughtscapism

Pingback: The Animals of Chernobyl – Trip Report, Day Three | Thoughtscapism