In my series 17 Questions about Glyphosate, last but not least comes a post about the integrity of research, how funding may influence research results, and what corporate involvement with scientists may entail. And if scientists mostly are not influenced by industry, why are there so many conflicting study results?

In my series 17 Questions about Glyphosate, last but not least comes a post about the integrity of research, how funding may influence research results, and what corporate involvement with scientists may entail. And if scientists mostly are not influenced by industry, why are there so many conflicting study results?

What about conflicts of interest and industry funding?

This question often comes up whether the one posing the question knows about a definite connection to industry or not. Sometimes the concern goes as far as to include the ‘medical establishment’ as a pressuring actor that hinders scientists from publishing differing results. What many don’t realise, is that new and different results are actually the best thing a scientist could hope for. As long as you have quality evidence supporting your findings, publishing new results that go against an earlier understanding is one of the most exciting things that could happen to a scientist.

What comes to connections to industry, there is a worrisome state of affairs around the concept ‘Conflicts of interest’, or COI. In discussions online people often look first at who has funded a study. That in itself is fine, and it’s good information to have in the background. But that is not what usually happens. Instead, if they find that the study authors have an (openly declared) COI of some kind, they announce that to be the end of discussion – the study’s findings can be dismissed directly.

This break-down of 197 randomly selected safety studies on GE foods demonstrates the lack of funding bias: all the studies follow the same trend no matter funding source. The GENERA database has a collection of over a thousand studies and their funding information. See also About Those Industry Funded GMO Studies by Marc Brazeau.

This is intellectual dishonesty at its finest: using the existence of a COI as a magic weapon that frees one from the need to consider evidence, especially if one does not like the direction of its conclusions. In some contexts, merely implying that a scientist has a connection with industry – any connection, at any point of their career, however flimsy – is taken as near-certain evidence of fraud. Take the case of Kevin Folta: an independent genetics researcher whose non-profit outreach program, where he volunteered his time, received modest amounts of travel money from Monsanto for speaking engagements. When this came to light, he was widely trashed in social media, personally harassed, and his office was broken into – the whole campaign was an attempt to smear him as if he was ‘bought and paid for’.

I was once laughed at by a commenter who implied how ridiculous it was even to consider my words on vaccines – because I had once worked for a pharmaceutical company (but not in vaccine research). Take a moment to think about this. Think of some of your previous employers – or even current ones – what is your relationship to them? Would you wish to distort the truth in order to twist important facts so that they appear in some former employers favour? What lengths would a company have to go to, even a current one, to get you to compromise your integrity by committing fraud, and in so doing endangering your credibility and career?

Being bought and paid for is far less likely, than the option that people on any side of a debate – activists, skeptics, scientists – simply believe they are doing the right thing and think they are seeing things from the correct perspective. But if they all equally sincerely believe they are doing the right thing, how can we know who is actually in the right? The best tool for determining which view indeed lies closest to the truth remains the objective assessment of data. We are easily blinded by our biases, especially when our beliefs are an essential part of our identity. Whoever disagrees with you is not the enemy – the important fight is against our own cognitive failings. And this IS the science fight: to weed out bias, and get us closer to understanding what truly goes on in the world.

It is bizarre for people to declare a person ‘dirty’ on the basis of them building bridges between the academia and the industry, or for agreeing to test an important part of a company’s research at an independent location, or even for something as simple as having once earned a living in one’s field. But it does make for a convenient excuse for not having to listen to anyone with the relevant know-how, and for not getting into the complicated workings of the scientific process.

In science, credibility is everything

It’s important to keep in mind that having a COI does not mean that a study is biased. Alison Bernstein, aka Mommy, PhD, has written a great piece about this, titled Credibility is Our Currency, over at Biofortified:

While conflicts of interest may lead to research misconduct, they are not evidence of misconduct nor are conflicts of interest necessarily misconduct on their own. The presence of a COI may demand closer scrutiny of the research to determine if misconduct or bias affected the interpretation of the results. However, a COI itself is not research misconduct, nor does the existence of a COI automatically mean that research misconduct occurred. This is not to minimize the importance of the disclosure of COIs. It is this very transparency that allows us to identify problems, limit COIs and scrutinize research that may be biased. In science, credibility is our currency.

No sweetening the deal here

It is very grave and risky business for a researcher to commit misconduct, one that could cost them their entire career. Not only that, to become a researcher is a painstaking and not very well paying process that is hardly attractive if your primary motivation is monetary gain, and unless you actually are interested in finding out how the world actually works. Turning one’s back on all of that may not happen so easily. For perspective, there are a couple of striking examples of results that even go against the clear COI of their authors: Honey-industry funds a comparison study of honey, and the researchers find honey is not better than high fructose corn syrup:

Honey has an aura of purity and naturalness. Fresh air, birdsong, forests and meadows. High-fructose corn sweetener? Not so much. So you might think that honey is better for you. But a study published this month compared the health effects of honey and the processed sweetener and found no significant differences.

The honey industry funded scientists studying honey. And the scientists… swiftly surrender their morals and go against the essence of being a scientists in order to produce a paper that shows how great honey is? If you’ve listened to much of the anti-glyphosate and anti-GMO rhetoric, that surely is the logical conclusion. Funnily enough, in this case the scientists found nothing to make the honey industry happy and went forward to report it anyway. Fancy that! Could it be that these scientists were in it for the science?

There was another ironic case, when an anti-vaccination organisation funded an autism study, and the study showed no connection between the condition and vaccines. The organisation had hoped to confirm a preliminary inclination of some measurable difference in monkey babies’ development after vaccines, but the data came up empty. Needless to say, the group behind the funding was unhappy with its results: Administration of thimerosal-containing vaccines to infant rhesus macaques does not result in autism-like behavior or neuropathology. Newsweek reported on it as well: Anti-vaxxers accidentally fund a study showing no link between autism and vaccines.

But biased studies do get published

So COI alone is definitely not proof of manipulated data or even a study conclusion drawn in the funding parties’ favour. But that doesn’t mean that research misconduct motivated by a conflict of interest could not happen or would not have happened at all. Sadly, sometimes even when a scientist is directly and fully funded by industry advocacy groups, and a Freedom Of Information email request uncovers a clearly communicated expectation that the scientist should find and publish evidence to support a preconceived conclusion, the COIs are swept under the rug by the media.

This, in fact, is what happened with the only case of misconduct/undeclared COI which has come to light on a study of glyphosate. This particular interest which conflicted with objectivity of the research was the interest to find evidence that would reflect negatively on glyphosate and genetically modified crops. The case concerns economist Charles Benbrook and his undisclosed ties to the organic industry, which ended with him losing his position at Washington State University. It was reported on FarmOnline Emails expose anti-GM science for hire, and over at Genetic Literacy Project here and here:

University of Melbourne senior lecturer in food biotechnology and microbiology, agriculture and food systems David Tribe said the FOI email exchange showed that there was a PR plan to produce a predetermined outcome on the efficacy of GMs — not a scientific one.

“This exchange shows that Kailis is prepared to pay for research that has a preordained outcome and is confirmation of bias,” he said.

The hard currency of evidence

But even before the undeclared and inappropriate conflicts of interest came to light, the most important analysis of Benbrook’s claims had already been made. Secondary to any potential agenda or bias he might have had, scientists went straight to the data presented in his studies, they critically evaluated his methods, and pointed out how the conclusions he drew ignored some important factors entirely. They focused at first hand not on what his monetary incentives may have been, but on the value of his work from the perspective of the only hard currency in science: that of evidence.

An example of the hierarchy of evidence in human health topics Wikimedia CC BY-SA 4.0

Evidence is what we should use to evaluate a claim, whether we like the claim or not. Resorting to smear-tactics only obscures the really important discussion underneath. If we want to understand how the world works, critical thinking and careful evaluation of data is what counts.

Some people look at cases of misconduct (cases do get revealed, and papers retracted), at COIs, at single studies which never get confirmed, or point in starkly different directions, and say that science is broken. But this is just the messy process of science in action. Could the process be improved? Certainly, it should be, and improvements do happen.

Meanwhile, scientific process is still, has been for a long time, and will continue to be the best bet we have at getting at true knowledge. This is why we should turn to science with our questions. No matter how much science improves, however, it will always be true that a single study does not a fact make. Science is about degrees of uncertainty – only through entire bodies of research, which together point in a certain logical direction, can we come to any kind of less uncertain conclusion about how the world actually seems to work. A great look at the faulty sides of science and analysis of its self-correcting nature can be found on the journalist blog fivethirtyeight. They write:

…headline-grabbing cases of misconduct and fraud are mere distractions. The state of our science is strong, but it’s plagued by a universal problem: Science is hard — really fucking hard.

If we’re going to rely on science as a means for reaching the truth — and it’s still the best tool we have — it’s important that we understand and respect just how difficult it is to get a rigorous result.

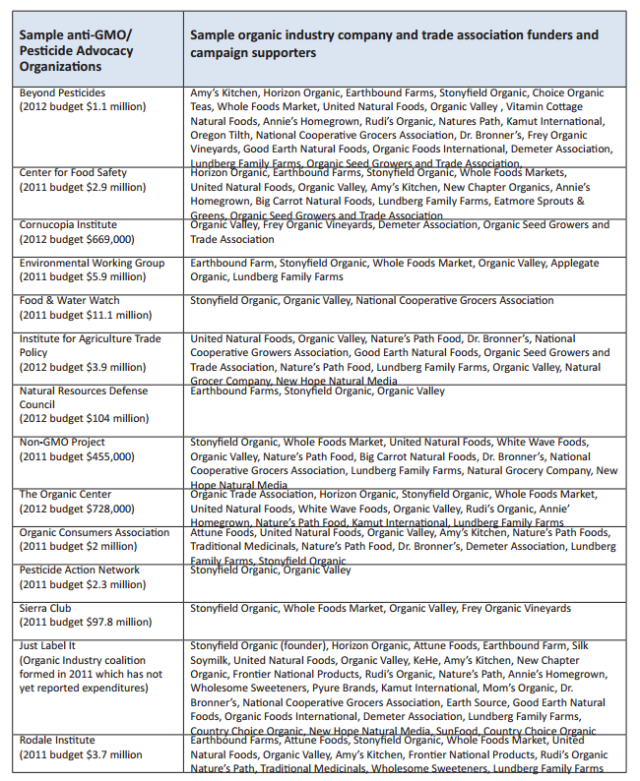

In fact, industry influence has rarely if never managed to sway the state of research – one biased study quickly gets left behind as confirmations fail. This is why the bigger industry bias in fact can be found in marketing and political lobbying, as succinctly presented here by the farmer and science communicator Farm Babe. An academics review paper on Organic Marketing Report shows that wealth of funding is being poured into organisations which oppose pesticides, spend their fund by purchasing adds and billboard campaigns, and targeting parents and health-conscious consumers by scare-campaigns.

The intricate network of activist ‘grass-root’ organisations who are against pesticides and biotechnology and their funding ties to the organic industry from the Organic Market Report.

But haven’t industries influenced the state of research before?

Even in the much publicised recent case of the 70s sugar industry scandal, it’s important to remember the following, very well outlined in this piece: the nutritional sciences field was full of incomplete and uncertain results, and there were many independent scientists looking at both, the health effects of fats as well as sugars, and some simply thought the evidence on one or other was more alarming. One of the scientists who already subscribed to the idea that sugar was the lesser evil, later received undisclosed funding from the sugar industry – a clear breach of research ethics. These ideas were already being battled by several independent scientists, however, and the funding simply aligned with a team who already thought there was more support for the dangers of fats (there are dangers to fats, but that doesn’t mean sugar isn’t also harmful) and the field of human nutrition is an especially hard one, seeing as it is hard to conduct controlled long-time experiments.

Nutritional scientist Andrew Brown examines the topic well in his article, So what if the sugar industry funds research? Science is science, in Slate. He writes:

…a single narrative review was unlikely to sway academic thought for 50 years. The evidence that the nutrition evidence-base was compromised by the review is weak.

[…]

Down-weighting or ignoring data from people or sources we dislike without empirical reasons to mistrust the data is to willingly position ourselves in a world with less information in the thin hope that the remaining information will somehow be better—but with no such guarantees.

Science has come a long way from those times both in our knowledge about nutrition and the metabolism, as well as the regular scrutiny of funding sources – this kind of undisclosed sponsorship would never have gone unnoticed today. In any case, scientists and research are much more difficult to influence than public image in the minds of consumers (as the tobacco industry, for instance, learned a long time ago, well outlined in this piece by the Credible Hulk), and the returns of investment are much greater in an avenue where teams of independent scientists aren’t continually poised to go on picking apart any flaws or inconsistencies in the narratives offered.

Thank you for reading my series on glyphosate. A few concluding words…

New innovative research is always welcome, especially for a substance as widely used as glyphosate. We should always strive to honestly evaluate the evidence before forming our views on a topic. As the numerous examples of this series of 17 Questions About Glyphosate demonstrate, the greatest glyphosate-resistance around may indeed be one of a more psychological kind: it has become a fix idea in many minds that glyphosate must be behind a whole host of ills in our world. Trying desperately to fit the evidence into the idea, rather than allowing our ideas to be shaped by the evidence, is what has resulted in this process of claim-whack-a-mole. I have no doubt that next month some new variation of glyphosate-sensationalist news will give wings to yet another far-fetched or misleading claim. The game might never come to a real conclusion, for it may be that for many, the only acceptable kind of world is one where glyphosate can only be a bad guy.

If you are interested in other environmental or health topics, you can find my other pieces and further resources under Farming and GMOs, The Environment, and Vaccines and Health. If you would like to have a discussion in the comments below, please take note of my Commenting policy. In a nutshell:

- Be respectful.

- Back up your claims with evidence.

Thanks for all your hard work…this is stuff I understood, but did not have the time to write. You are doing a great service to the understanding of science by lay-people.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: 17 of 17 – Can Glyphosate Research Be Trusted? – GMO Building Blocks

This is a really great piece. Congratulations and profound thanks for putting all the facts together.

LikeLike