After visiting the town where people had remained despite orders to move, we had spent our two days in the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone talking to groups of field researchers, scouring the wetland bushes by the cooling pond, and hiking the grasslands in search of a herd of Przewalski horses within a fifteen kilometer radius from the accident site. On our last day, we finally got a tour of the power plant itself.

Our guide was an international PR representative of the power plant, a man whom the researchers had met before. He was a very experienced and well-spoken, and had a flair for showmanship, too – I got the feeling that he knew how to give the visitors what they wanted out of their tour.

Our scientist hosts told us that they had earlier caught the same guide telling the visitors tall tales about the death count of the accident. I was uncomfortably aware that people may visit the place “for kicks,” in order to revel in an aura of horror, in the process unnecessarily mischaracterizing the true nature of the tragedy. Drawbacks of disaster tourism. The scarier the stories the guides could tell them about the place, the greater the dramatic effect.

After our plant tour was already over, when asked if he might sometimes embellish the truth a bit in the spirit of telling a more dramatic story, our guide neither denied or confirmed directly, merely smiled and shrugged in a suggestive fashion.

It turned out we did some embellishing of our own 😉 unwittingly confirming the Simpsons view of the glowing green nuclear plants. Jim Smith (on the right in the photo) had kindly loaned his fancy geiger meter to me for the duration of my visit. It had nice luminous green numbers on its display.

The readings were particularly interesting right around there: we were in the turbine hall that is wall-to-wall with the accident site, some 50 meters from the molten reactor itself. I recorded the peak rate of my trip a few meters from that spot, at 23.7 µSv/h (microsieverts per hour) – about a hundred times higher than the global average background radiation.

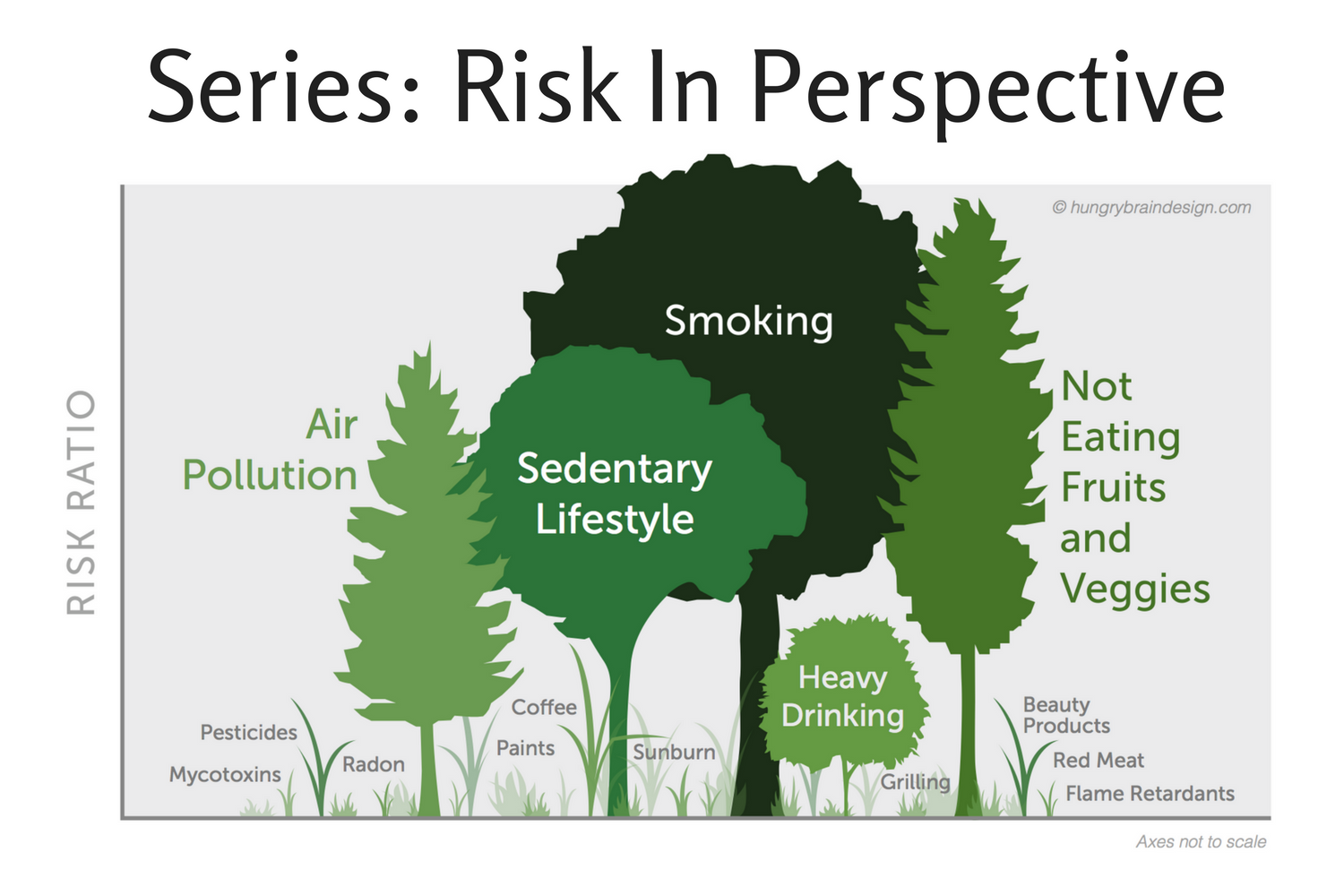

The radiation nerd that I am, I was pretty excited – the only time I’ve clocked higher was when I got to hug a warm cask of used nuclear fuel. Even then, I would have had to keep hugging that cask for ten weeks straight to approach the exposures where we could say anything half-certain about an increase in life-time cancer risk (statistically speaking, when exposed populations number in the hundreds of thousands or millions). At that point, it would be on par with the risks of having a drink of alcohol per day. I’ve laid it out in more detail in Radiation and Cancer Risk – What Do We Know.

In other words, the levels in the turbine were not worrisome, although the strict safety procedures (commonplace in all nuclear contexts) certainly make them seem ominous.

What comes to disaster tourism, our official guide to the Zone, a tough-looking pony-tailed man who stayed with us throughout the trip, told us that he was personally against the industry of sight-seeing in Chernobyl. If it was up to him, he’d want the area open for scientists and artists only.

I can see that the growing industry of touring Chernobyl is a nuanced topic. Helping the local economy would be important (if the money goes their way), as well as supporting the conservation efforts – the Chernobyl Biosphere group hopes the area will finally be granted the official status of a wildlife park.

I understand why people would want to see Chernobyl. I feel incredibly lucky to have visited it myself. But I am also not keen on the idea of having streams of tourists coming there without an appreciation of the complex political and psychological aspects that are responsible for most of what has happened in the Zone.

Abusing the trust of your citizens, as the Soviet Union did, and then taking their homes away, as happened during the mass evacuations, have grave consequences on people’s lives – more so than any radioactive contamination of the area has achieved. As the UN body studying effects of atomic radiation, UNSCEAR, has concluded:

“The mental health impact of Chernobyl is the largest public health problem caused by the accident to date.”

The UNSCEAR report elaborates on the many causes behind those mental effects, including fear, distrust, as well as economical and political factors. If the Chernobyl tourism industry contributes to the image of inflated fear and doom around radiation, it could do more harm than good.

An Effort at Responsible Communication

I wanted to use my trip to help set the radiation exposures in perspective. I hoped I could get people to look past the fear reaction we have to the mere detection of radiation (although not in natural contexts!), and focus on the more realistic view of the magnitude of risks associated with radiation instead.

My posts about it on Facebook garnered a great deal of discussion. I wrote:

We imagine Chernobyl would be a place of particularly high radiation, right? And that’s true: there are places within the Zone where background levels climb higher than most places on earth. However, the absolute majority of the Zone is at perfectly mundane levels of 0.1 µSv/h or lower, identical to the typical measurements I get walking around in Switzerland.

It’s not particularly easy to accumulate doses as large as we receive just from cross-European flights – not even during a full two-day stay in the Exclusion Zone, including a venture to the turbine hall that is wall-to-wall with the accident site, some 50 meters from the molten reactor itself.

By the way, the levels we are exposed to on flights are not considered dangerous. A good piece on radiation on flights here at What is nuclear.

Many people who saw my post were surprised by the information, and said that my measurements could not be accurate. It’s great to stop and question the validity of something you see on the internet. Yay! The information is quite readily available. Radiation levels on flights, as well as those in various parts of the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone can be confirmed from multiple reliable sources. The levels themselves are not controversial. I only wished to draw attention to them by my personal example in a way which may make the information more approachable and relatable to others.

Many protested, claiming that in one or other way the radiation in the Zone must be much more dangerous. That there were threats I was completely overlooking.

We live in a world full of risks, and we should acknowledge them. Nuclear power and its accompanying ionizing radiation are no exceptions to that rule. It is a good idea, for instance, to be mindful not to ingest or inhale dust in possible hotspots like those in the Red Forest, should one be disturbing the soil in areas with markedly higher radiation levels.

But any reference to a factual magnitude of the suggested added risks is absent in these discussions. People living off the land in the Zone, for instance, have only received about a CT-scan’s worth of extra radiation in 25 years.

Material contamination (mud, stones, dust on clothes/shoes) never triggered any of the several radiation check point scans we passed in our visit. Several of the researchers I talked to who have been doing field-work in the Zone for 10-30 years, could together recall one occasion when one of their teammates was stopped at a checkpoint due to mud on their shoe with a higher radiation reading. This was remediated with brushing.

In the case of radiation, distorted ideas about the size of the risks has already lead to thousands of deaths and serious health impacts – consequences of fear-reactions. These are real, tangible effects, and we have to take responsibility for them just as much as we need to take into account realistic risks from radiation.

From a public health perspective, the way we give information, communicate, and the kind of messages we send with our policy measures has a clear and real effect on people’s health. Where effects on physical health are minor, the exaggeration of such risks becomes a larger health risk on its own right. Information can also be toxic, in this sense. We should always consider the importance of context and scale when lifting up possible risks.

Visiting Chernobyl is an opportunity to reflect on a tragic piece of history, but also our own risk perceptions. It is not dangerous. It offers a great chance to observe thriving wildlife – no three headed fish or glow-in-the-dark rats among them.

Thanks for reading! Whole trip report series:

Pingback: The Animals of Chernobyl – Trip Report, Day Three | Thoughtscapism

Pingback: Visiting Chernobyl, Day One, The Most Dangerous Part of the Trip: Kyiv | Thoughtscapism

Pingback: The Town That Remained Despite the Chernobyl Accident | Thoughtscapism

I think these posts are extremely helpful in giving people a more realistic perspective of the risks of radioactivity. One way to add to this is to compare other risks, which is also something that you do well. I think an interesting point to make is that official policies on what is considered acceptable have an enormous impact on perception of risk. I think this is the fundamental reason why people fear radioactivity far more than they fear ambient air pollution, despite the fact that the latter kills more people each year (> 7 million). The officially ‘acceptable’ levels for ambient air pollution (e.g. for PM2.5 particles) are at least 100 fold more dangerous than the ‘acceptable levels of radioactivity. That is why we are happy to be exposed to air pollution in most cities (e.g. London and Tokyo) that shortens our lives more than would living in the Fukushima radioactivity exclusion zone. My recommendation would be that set limits on environmental pollutants at the same level of risk. We can leave up to the voters to decide whether we should raise limits for radioactivity or lower limits for ambient air pollution. My preference would be to adjust both to some reasonable level.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Dear Anton,

Thanks so much for your insightful comment. Too bad I can’t like it more times! This is exactly what has been bothering me about regulation of risks. It has lead to governments acting in ways that put people in harms way – because surely it’s ok to take drastic action to avoid the slightest possibility of one risk? No, it’s not. First: do no harm.

I got a chance to talk to Nuclear Energy Agency at their Risk Comm workshop in Paris 2019, and I asked for precisely this. From my talk: “I look to you, as regulators, with the same hard but fair demand: risks don’t exist in a vacuum. We owe it to the public to set these risks in context, and we can not responsibly give one industry a free pass while we handle minuscule risks of another with an iron grip. That’s not in anyone’s best interest. We need to consider all factors influencing our quality of life. Not only radiation. It’s no small task, as our future depends on it.”

And they heard me! Petteri Tiippana from STUK, the leader of the Finnish radiation protection agency, even mentioned it in his closing comments: ”We should empower the public w information so they can make adequate judgements and choices […] It’s more sensitive for us regulators to address, as Iida was saying, whether we could regulate risks more in context w other kinds of risk.

[…] We might benefit from science on risks – why are these risks perceived as so much higher. What’s there for us to learn.” https://www.facebook.com/Thoughtscapism/posts/2425876917530906

So clearly, it’s not exactly something that would be easy or quick for them to implement. But that doesn’t mean that it wouldn’t be the right call for societies.

I wrote about it here, too: “We can’t allow our policies, governments, and regulatory agencies to continue reacting out of fear, and considering risks of radiation in a vacuum. It is a fundamental principle of bioethics that all medical students are taught throughout the world: that it may be better not to do something, or even to do nothing, than to risk causing more harm than good.

We must hold our government and regulatory bodies accountable to the same basic principle of ‘first, do no harm‘ – for the sake of the public they are supposed to be protecting.”

Sorry for the novel of a response – the things you said really got me going. 🙂

Thanks again for reading and commenting!

Hope you have a great day.

Iida/Thoughtscapism

LikeLike

Thank you for your interesting document. I have been particularly interested in reading the numbers you notes about “radioactivity level” (in micro Sieverts/sec); these numbers are relatively reassuring; especially if we consider the levels of natural radioactivity in certain exceptional regions of our earth (in Iran ou in Bresil where levels somewhere reach (if my memory is good) 70 more than natural level in Paris; or the level of radiations you can receive during an airplane flight.

As I am French, I receive your documents in a French version; I appreciate the delicate attention but I would prefer reading your paper directly in English: when I read the French version of your paper, a serious paper about a serious subject, I am not prepared smiling while reading it; and from smile to laugh there is only a small step to take… The Google French (I suppose the Finnish too) is very creative with language…So , if it is possible I would prefer receive the document in English.

As you wrote in your paper, in Tchernobyl disaster ,much people died or became sick because of fear more than because of radiations. And i remember verses written by a French poet in 17 th century:

“Je ne découvre rien propre à me secourir

Et la peur de la mort me fait déjà mourir » (Pierre Corneille)

I don’t dare use the Finnish google translator for this, because I have no idea about the correctness, but in English this could be something like this:

“I can’t see anything able to rescue me , and the fear of my death is now killing me ” *Pierre Arthuis*

LikeLike